To Alfredo Guevara

To my children, Tancrde and Axel

ALLEN LANE

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R ORL, England

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York rooi4, USA

Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4P 2Y3

(a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.)

Penguin Ireland, 25 St Stephens Green, Dublin 2, Ireland

(a division of Penguin Books Ltd)

Penguin Group (Australia), 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia

(a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd)

Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, II Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi - 110 017, India

Penguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive, Rosedale, North Shore 0632, New Zealand

(a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd)

Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank, Johannesburg 2196, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WCZR ORL, England

www.penguin.com

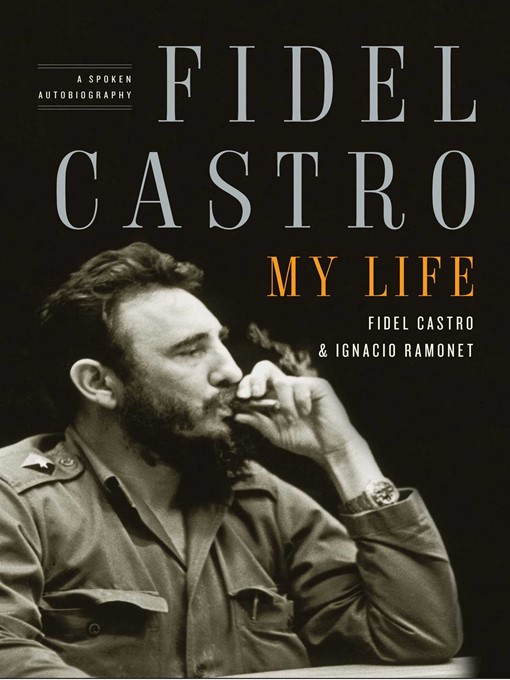

Fidel Castro: Biografia a dos voces first published in Spain by Random House Mondadori 2006

Revised edition published 2007

This translation first published by Allen Lane 2007

Copyright Ignacio Ramonet and Random House Mondadori, 2006, 2007

Translation copyright Andrew Hurley, 2007

The moral right of the author and translator has been asserted

All rights reserved

Without limiting the rights under copyright

reserved above, no part of this publication may be

reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system,

or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical,

photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the prior

written permission of both the copyright owner and

the above publisher of this book

Set in PostScript Adobe Sabon

Typeset by Rowland Phototypesetting Ltd, Bury St Edmunds, Suffolk

Printed in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, St Ives plc

ISBN: 978-0-713-99920-4

www.greenpenguin.co.uk

Contents

A Hundred Hours with Fidel

It was two oclock in the morning, and wed been talking for hours. We were in his personal office in the Palacio de la Revolucion, a big, austere room with a high ceiling and a large expanse of windows framed with light-coloured curtains that opened out on to a broad balcony from which one could see one of Havanas main avenues. An immense bookshelf on one wall, and before it, a long, heavy desk covered with books and documents. Everything very neat. In among the books on the bookshelves and on small tables at each end of the couch were a bronze figure and bust of the Apostle of Liberty Jose Marti, and a bust of Abraham Lincoln. In one corner, a wire sculpture of Don Quixote astride his skinny steed Rocinante. And on the walls, in addition to a large oil portrait of Camilo Cienfuegos, one of Castros main lieutenants in the Sierra Maestra, three framed documents: a handwritten letter by Simon Bolivar, a signed photograph of Ernest Hemingway holding up a huge swordfish (To Dr. Fidel Castro - May you hook one like this in the well at Cojimar. In friendship, Ernest Hemingway), and a photograph of his father, Angel Castro, on his arrival from distant Galicia in 1895.

Sitting before me - tall, robust, well built, his beard almost white, wearing his ever-present impeccable olive-green uniform with no ribbons or decorations and showing not the slightest trace of weariness despite the lateness of the hour - Fidel answered calmly, sometimes in a voice so low that it was just a whisper, almost inaudible. This was in late January 2003, and we were beginning the first series of long conversations that would bring me back to Cuba several times over the succeeding months, through to December 2005.

The idea for this conversation had come up a year earlier, in February 2002. Id gone to Havana to give a lecture at the Havana Book Fair. Joseph Stiglitz, winner of the Nobel Prize for Economics in 2001, was also there. Fidel introduced me to him by saying, Hes an economist and an American, but the most radical one Ive ever seen. Beside him, Im a moderate. Fidel and I started talking about neoliberal globalization and the World Social Forum in Porto Alegre, which I was just returning from. Fidel wanted to know all about it - the subjects that had been debated there, the seminars, the participants, the forecasts ... He expressed his admiration for the alternative globalization movement: A new generation of rebels has emerged, he said, many of them Americans, who are employing new methods of protest and making the lords of the world tremble. Ideas are more important than weapons. Except for violence, all arguments should be used to combat globalization.

As always, ideas rushed like a bubbling stream from Fidel. Stiglitz and I listened in fascination. He had an all-encompassing vision of globalization, its consequences and ways of confronting them; his arguments, of a great modernity and cleverness, made patent those qualities that many biographers have noted in him: his sense of strategy, his ability to read a concrete situation, and his quickness at analysis. To all that was added experience accumulated over so many years of governing, resistance and combat.

As I listened to him, it struck me as unfair that the newer generations knew so little about his life and career and that, as unconscious victims of constant anti-Castro propaganda, so many of those in Europe who were committed to the alternative globalization movement, especially the young people, considered him a relic of the Cold War, a leader left over from a stage of modern history that had now passed, a man who had little to contribute to the struggles of the twenty-first century.

Even today, and even in the inner circles of the Left, many people criticize, distrust, even outright oppose the Castro regime in Havana. And though throughout Latin America the Cuban Revolution continues to inspire enthusiasm among leftist social movements and many intellectuals, in Europe it is the subject of controversy. It is increasingly difficult, in fact, to find anyone - for or against the Cuban Revolution - who, asked to sum up Castro and his years in power, can give a serene, dispassionate opinion.

I had just published a short book of conversations with Subcomandante Marcos, the romantic, galactic leader of the Zapatistas in Mexico. Fidel had read it and found it interesting. I suggested that he and I do something similar, but on a larger scale. He has never written his memoirs, and its almost certain that for lack of time he never will. What I proposed would be, then, a kind of autobiography a deux, though in the form of a conversation; it would be Fidel Castros political testament, an oral summing-up of Fidel Castros life by Fidel himself at almost eighty and more than half a century after the attack on the Moncada barracks in Santiago de Cuba in 1953 - the moment when, to some degree, his public life began.

Few men have known the glory of entering the pages of both history and legend while they are still alive. Fidel is one of them. He is the last sacred giant of international politics. He belongs to the generation of mythical insurgents - Nelson Mandela, Ho Chi Minh, Patrice Lumumba, Amilcar Cabral, Che Guevara, Carlos Marighela, - who, pursuing an ideal of justice, threw themselves into political action in the years following the Second World War. These were men who hoped to change a world of inequalities and discrimination, a world polarized by the Cold War between the Soviet Union and the United States. Like thousands of progressives and intellectuals around the world, among them the most brilliant of men and women, that generation honestly thought that Communism promised a bright and shining future, and that injustice, racism and poverty could be wiped off the face of the earth in a matter of just decades.