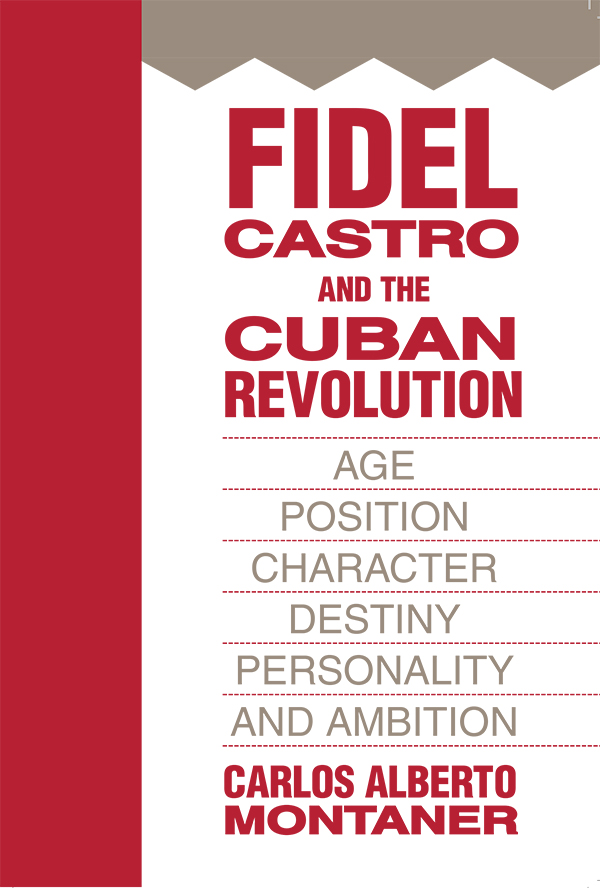

FIDEL

CASTRO

AND THE

CUBAN

REVOLUTION

First published 1989 by Transaction Publishers

Published 2017 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017, USA

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Copyright 1989 by Taylor & Francis.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notice:

Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

Library of Congress Catalog Number: 88-30071

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Montaner, Carlos Alberto.

Fidel Castro and the Cuban Revolution: age, position, character, destiny, personality, and ambition / Carlos Alberto Montaner.

p. cm.

Bibliography: p.

Includes index.

ISBN 0-88738-235-5

1. CubaHistory1959- 2. Castro, Fidel, 1927- I. Title.

F1788.M573 1989

972.91064dcl9

88-30071

CIP

ISBN 13: 978-1-4128-0731-9 (pbk)

Contents

The entire documentary part of this book has been made possible thanks to the efficiency and disinterested help of Laura Ymayo. I acknowledge my first debt of gratitude to her; and, in addition, to Agustn Alles, Humberto Medrano, Juana Castro Ruz, Ramn M. Barqun, Mara Luisa Matos, Manolo Rodrguez Fleitas, Luis Conte Agero, Nazario Sargn, Jorge Gutirrez, Rosa Abella, Guillermo G. Mrmol, Ana Rosa Nez, Lev Marrero, Mario Villar Roces, Miguel Olba Benito, Angel Gonzlez, Tony Fernndez, Tulio Daz Rivera, Juan Tapia Ruano, Lesbia Varona, Leonor Villa, Ariel Remos, Jesse Fernndez, Tony Evora, Gastn Fernndez de la Torriente, Julio Rodrguez, M.C., Aurora Calvio, L.M., and to all the others, some of them unnamable, who have contributed to the task.

I want to dispel any erroneous notions. I am a Cuban who for strictly political reasons left Cuba in 1961. I was not adversely affected by the revolutions economic policies and could have easily benefited from the changes that have taken place in my country. I call the readers attention to these aspects of my background to ward off suspicious conjectures, while admitting that my being a Cuban exile can call into question the objectivity of my evaluations regarding Cubas revolutionary process. I refer the reader interested in the subject of exiles objectivity to an illuminating essay in Cuban Communism, Social Science Writing on Post-Revolutionary Cuba, by Irving Louis Horowitz, a scholar who is beyond the suspicions that perhaps I arouse. In this essay, Horowitz points out that the most valuable and dispassionate studies on contemporary Cuba are the work of exiled Cuban intellectuals. Horowitzs findings are not surprising, since the first voices that should be taken into account for an analysis of any historical event are those of the main actors. None are more qualified to relate historical events vividly than those who, like Jonah, have lived them. An a priori rejection of the players opinions solely because he is an integral part of the drama is dangerous. The acceptance of such criteria would force us to ignore what men like Franklin, Jefferson, or Paine wrote about the American Revolution of 1776. That would be both unjust and unwise.

A first version of this book appeared in 1976 entitled Informe secreto sobre la revolucin Cubana (Secret Report on the Cuban Revolution), and the following year it was reissued with an appendix on the Cuban presence in Angola. With this title as well, it was translated and published in English in 1981.

There are three reasons why the name of the book should now be changed. The first is that this versionI believe, definitiveoffers a different structure from the original in that certain essays were eliminated, others were recast, and some new ones were added about the most important events in the last few years. The second is that what in 1976 was secret today is public domain, and it would not be in good taste to lure the reader with a promise that would inevitably turn out to be unfulfilled. The third and perhaps most important reason is that the new name, Fidel Castro and the Cuban Revolution, more faithfully reflects the contents of the book. Probably the least insignificant reflections of these papers have to do with the intense and definitive relation between the personality of Fidel Castro and the frightening history of the Cubans. Chapter after chapter I insist on this theme, perhaps because it seems to me impossible to understand the revolution without understanding Castro, perhaps because I am afraid that I will not be sufficiently persuasive in the key aspect of this now quite lengthy historical process.

Further clarifications: This is not a history book, but an essay in historical interpretation. I am assuming that the reader knows the rudiments of the question at hand. If he is lost, the most sensible thing to do is read Hugh Thomass Cuba: The Pursuit of Freedom, an incomparable manual of contemporary Cuban history. Fidel Castro and the Cuban Revolution is something different. When I decided to write it, I first faced a methodological question: How does one analyze a revolution? After attempts that floundered either in disorder or in the accumulation of facts, I chose to address a series of topics of general interest: Batista, Fidel, women, race, sex, the power structure, the opposition. I ventured to deal with them directly andI now realize with some embarrassmentalso with a certain intolerable ease. This collection of brief essays, despite its loose appearance, has hopefully a coherence that allows the reader to make a definite value judgment after he has finally put the book down. This is its aim. The reader, overburdened for years with contradictory information, will now be able to take a look behind the confusing images and formulate an unequivocal judgment about the Cuban Revolution. This book proposes to provide a general interpretation of events, and then to let one extract his own conclusions.

Publication of papers such as these has brought me in the past a good number of personal attacks and criticism. Since I know where these are coming from, I want to clarify a few things before any misinterpretations take place. To my benefit, the writers that have taken issue with me have been more repetitive than convincing. Their lack of imagination has allowed me, without great risks, to foresee the source of their main objections and articulate my answers. The procedure, certainly, is not very orthodox, but with it 1 am trying to keep what generally are no more than simplistic prejudices from being used as mufflers. I am not disregarding the possibility of my own mistakes in judgment in the analysis of certain facts, but this has to be proven with something more than mere growls.

First objection: The analysis of the Cuban revolution is invalid because the author is in exile and will thus always give a negative vision of that process.

If the above were true, Goytisolo, Arrabal, Madariaga, or Sender, for example, would have no authority to judge the Spanish political situation; Leninfrom London, from Switzerlandto talk about the Russia of the Czars. Or Mart, Sarmiento, and Bolvar, who wrote at such length from exile. Or Solzhenitsyn to write about the USSR which banished him by force. The opposite is probably true: Whether we like it or not, the most valuable testimonies are of those who have directly participated in events, be they winners or losers. These are slippery categories that time ends up by erasing. (Does anyone remember that Josephus, the great historian, was a loser?) But moreover, as Irving Louis Horowitz, an intellectual above suspicion, has pointed out, it happens that the best analyses of Castroism have been done by exiled academics (Mesa-Lago, Domnguez, Surez, Clark, et al.).