Burtyrki Books 2020, all rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means, electrical, mechanical or otherwise without the written permission of the copyright holder.

Publishers Note

Although in most cases we have retained the Authors original spelling and grammar to authentically reproduce the work of the Author and the original intent of such material, some additional notes and clarifications have been added for the modern readers benefit.

We have also made every effort to include all maps and illustrations of the original edition the limitations of formatting do not allow of including larger maps, we will upload as many of these maps as possible.

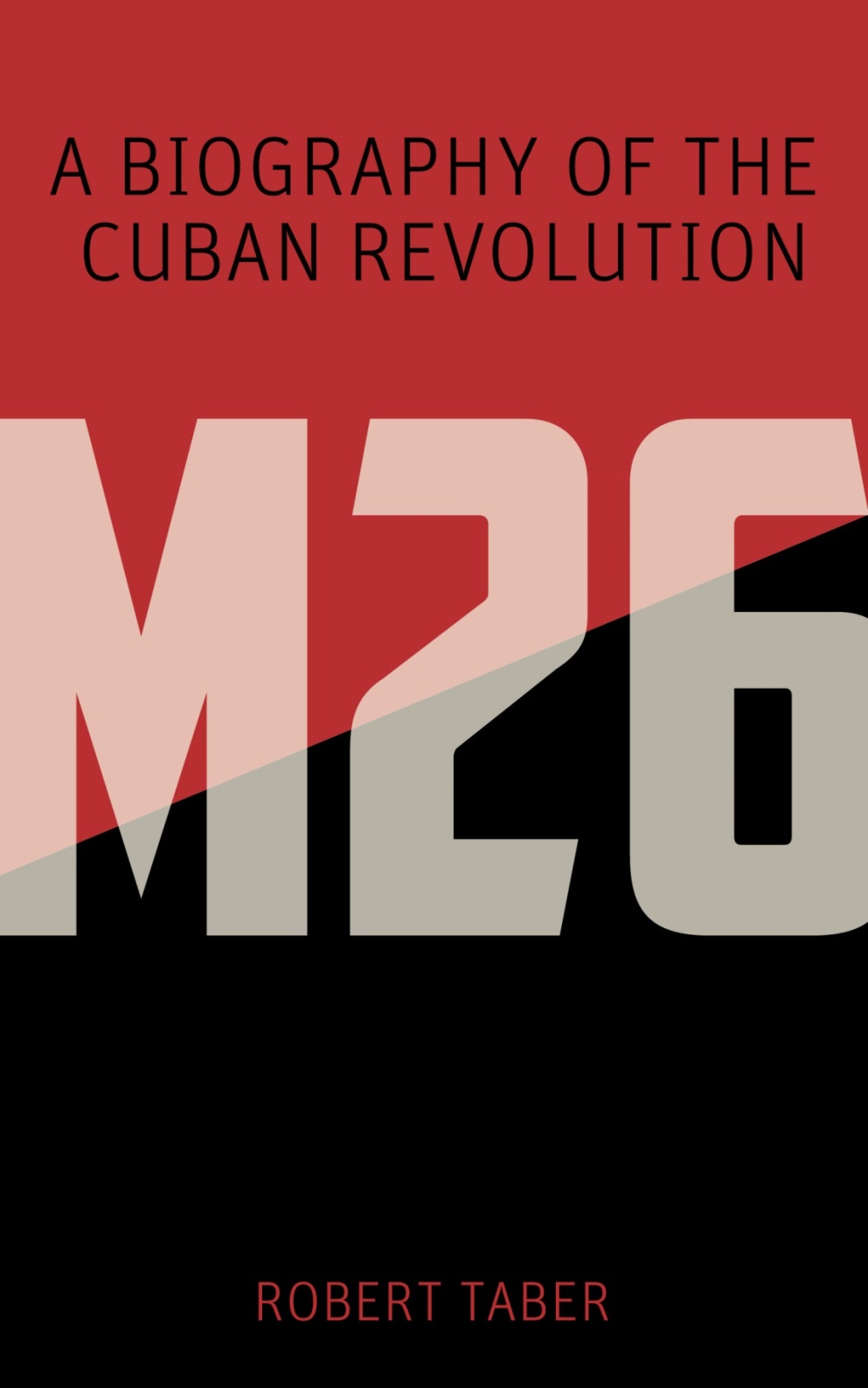

M-26

A Biography of the Cuban Revolution

ROBERT TABER

M-26 was originally published in 1961 by Lyle Stuart, New York.

* * *

At one moment Fidel Castro stands in the wing, bearded, costumed for melodrama, rifle in hand, rehearsing patriotic slogans as he awaits his entrance cue, to outward appearance merely another obscure political adventurer, angrily demanding liberty or death and all too evidently on the way to finding the latter.

Then, suddenly, he steps onto the stage of history and springs to full stature, a larger-than-life-sized Cuban hero, cut in the pattern of the Spanish conquistadores, defiant, quixotic, crying out for justice and compelling the attention of the world.

Who is he? What does he want? How has he accomplished what he has accomplished? What more will he do?

The revolutionary that I remember from my childhood impressions walked with a .45 pistol in his waistband, and wanted to live on his reputation. He had to be feared. He was capable of killing anyone. He came to the offices of the high functionaries with the air of a man who had to be heard. And in reality, one asked oneself, where was the revolution that these people made? Because there was no revolution, and there were very few revolutionaries. Fidel Castro

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Contents

Chapter One

THE NAME of Fidel Castro is known to newspaper readers in Cairo and Khartoum, it is a headline in Pravda; school teachers in Outer Mongolia mention it when they speak of the struggle against American imperialism, and a million Muscovites turn out to shout the Russian equivalent of Cuba s, Yanquis no! and Viva Fidel Castro! But in the United States, the questions persist, and are evidence of the obfuscation that clouds all aspects of the gathering American Revolution.

There is no novelty in this. The entire history of Cuba is, in American school books, a complicated lie. One must reach the graduate school level to get a glimmering of the truth. Few Americans knew, until well into 1959, that in 1952 a general named Batista seized power in Cuba at pistol point and was recognized by Washington as the legitimate ruler. Even fewer were aware that in 1953 a young attorney named Castro led an assault on a military barracks in Santiago de Cuba and was condemned to serve fifteen years in prison.

The Cuban insurrection of 1956-1958 was popularly regarded in the United States, until its successful conclusion and even for some while afterwards, as an adventure on the operatic scale, a peculiarly Latin-American compound of histrionics, headline hunting, and romantic idealism, sustained not so much by its own virtue as by the blunders of what began to emerge as a brutally stupid and corrupt ruling clique. This was the newspaper view.

Fidel Castro himself was an enigma, a figure of saintly and slightly sinister presence (Is he a Communist? Will he become a dictator?) passionate, eccentric, capable of exerting great personal magnetism and of attracting a fanatical following but not so surely, in the opinion of responsible political analysts, a leader who might direct the destinies of even a small nationor of a lucrative U.S. economic colony.

The skeptics who chose to view the entire Cuban struggle throughout as a prolonged political skirmish, a noisy tug of war between in and out parties, judged that he might serve well enough as a cats-paw for weightier men behind the scenes. Apparently it did not occur to them that there was, in reality, no one behind the scenes.

The only significant struggle, amazing in its simplicity, was the drama being enacted under the open sky, plainly visible to anyone who cared to investigate it.

What was in progress that the newspaper accounts and diplomatic reports of the time contrived to conceal? The insurrection that began in early 1957 in the Sierra Maestra mountains of Oriente Province was, however Lilliputian and improbable, the opening campaign of a Cuban civil war and the initial phase of a revolution that is in process, not merely in Cuba, but throughout the western hemisphere.

The fact is that neither Fidel Castro nor the Revolution conform to any stereotype. Both are fresh, new, radical; each has an existence complementary to the other. Fidel is as much the product of the Cuban Revolution as he is its librettist, stage director, and principal actor.

We have struck the spark of the Cuban Revolution, he declared in a television interview atop Cubas highest mountain in April of 1957, just a few months after his invasion of Oriente Province.

At the time he was a hunted fugitive with a price on his head and fewer than one hundred men under his command. Yet he could make his declaration with supreme confidence, knowing that the tinder had already been laid long since, and required only to be kindled by the spark of imagination which he himself was applying.

This is, of course, to reject superficial political interpretations of the Cuban Revolution. Our movement, says Fidel Castro, has no relationship with the political past of Cuba.

Who is Fidel Castro? One may anticipate conclusions by declaring at once that he is neither a Communist nor a tool of anyone. He describes his political philosophy as humanism, and might equally well define it as humanitarianism. Whatever else he may be, he is a radical thinker, a pragmatist, supremely a revolutionary: in many ways the prototype of the revolutionaries who even now begin to appear everywhere on the American scene.

He is, and they will be, anti-Yankee and nationalistic to the precise measure that the United States has played, or has seemed to play, the role of exploiter, friend of dictators, employer of gunboat diplomacy, and of what is aptly called, in the modern political slang, dollar diplomacy.

If the slogans of the Communists are heard in Cuba, and elsewhere in the Americas, increasingly, it is in the absence of better slogans. And if the economic formulae of the Cuban Revolution resemble those of the Russians and the Chinese, that, too, may be a measure of the failure of the theories that support what we like to call the American way of life, which is not truly American , but is only the privileged way of life of a relatively few millions of modern Romans in the United States and in U.S. enclaves abroad.

Who are the Cuban rebels? Fidel Castro Ruz was a young attorney, the third son of a Spanish immigrant who had achieved a modest fortune as a timber merchant and small sugar-cane planter ( colono is the Cuban term) in the rural municipality of Mayar, in Oriente Province. Marcelo Fernndez was a Crdenas grocers son. Abel Santamara was an accountant. Armando Harts father was a judge. Frank Pas was a young schoolmaster in Santiago de Cuba. Camilo Cienfuegos played minor league baseball in Texas. So it goes.

Next page