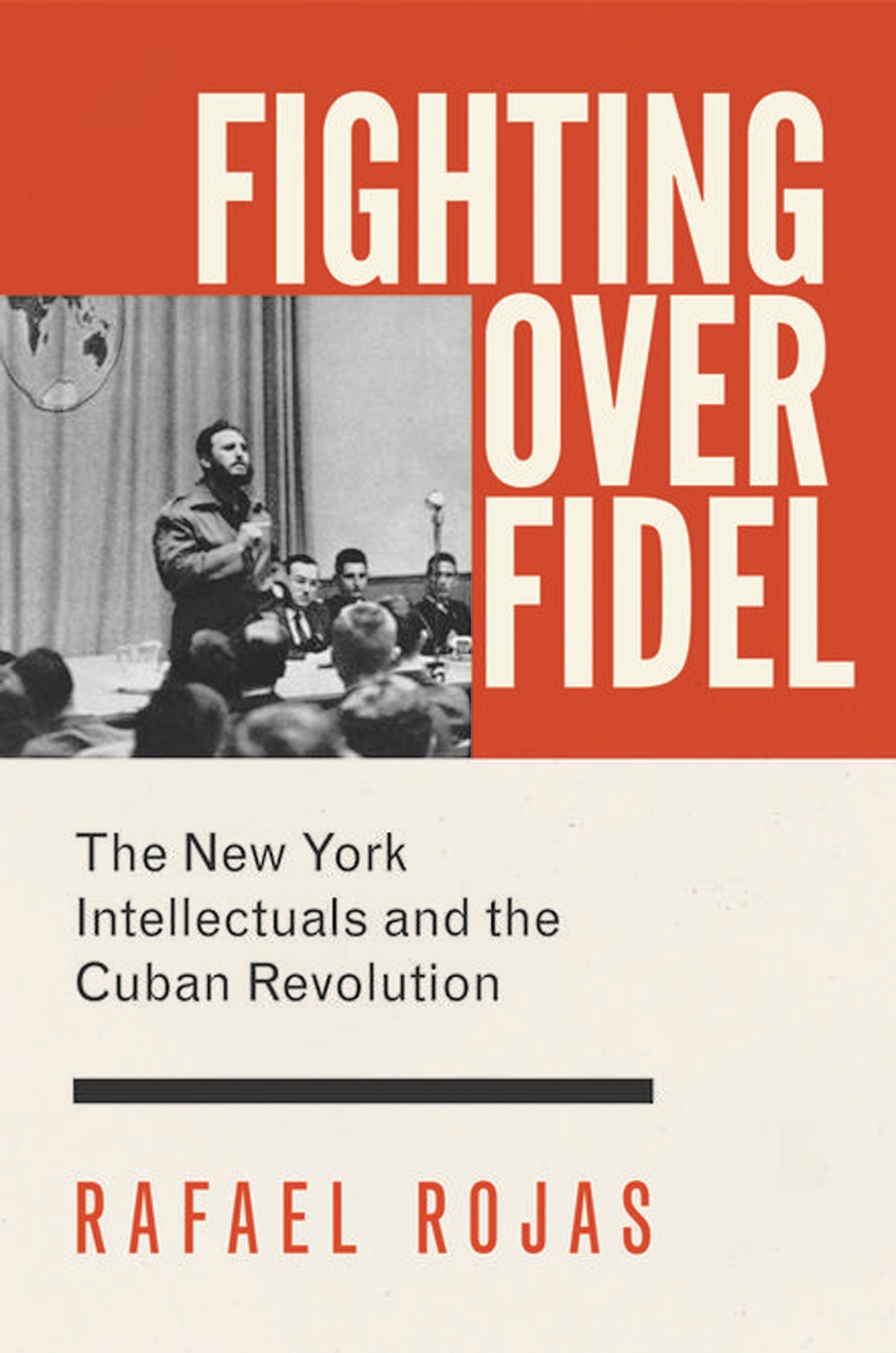

FIGHTING OVER FIDEL

FIGHTING OVER FIDEL

The New York Intellectuals and the Cuban Revolution

RAFAEL ROJAS

Translated by Carl Good

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

PRINCETON AND OXFORD

Copyright 2016 by Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street,

Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press,

6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TW

press.princeton.edu

Jacket image: Photograph of Fidel Castro, taken during his visit to Princeton University on April 20, 1959. Photograph by Richard A. Miller, from cover of Princeton Alumni Weekly, Volume LX, October 16, 1959, No. 5.

All Rights Reserved

ISBN 978-0-691-16951-4

Library of Congress Control Number: 2015951261

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

This book has been composed in Sabon LT Std

Printed on acid-free paper

Printed in the United States of America

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

To my father, Fernando Rojas valos (19352009), a Cuban doctor who joined the Revolution

And to my professor Arcadio Daz Quiones, who lived what is narrated here

CONTENTS

FIGHTING OVER FIDEL

INTRODUCTION

IN APRIL 1959, DURING HIS FIRST TRIP TO THE UNITED STATES after the triumph of the Cuban Revolution, Fidel Castro spent several days at Princeton University. His visit was organized by the American Whig-Cliosophic Society and the Woodrow Wilson Schools Special Program in American Civilization. These groups had learned of Castros trip to Washington, which had been sponsored by the American Society of Newspaper Editors, and with the encouragement of Roland T. Ely, a scholar of the Cuban sugar industry, they invited Castro to deliver a keynote address on April 20 for a seminar entitled, The United States and the Revolutionary Spirit.

Castro, who at the time held the post of Cuban prime minister, began his speech by clarifying that he was neither a theorist nor a historian of revolutions. As he reminded his audience, his knowledge of revolutions came rather from his engagement with a revolution that had taken place in a small Caribbean nation close to the United States. In his view, the Cuban Revolution had debunked several myths propagated by the Latin American Right: that a As he put it, the groups that took power in France and Russia used force and terror to form a new terror.

During his address, Castro situated his ideology well within the scope of a democratic American humanism shared by the United States and Latin America. The two regions, despite their cultural specificities, did not constitute different people, he assured his audience. At the conclusion of his remarks, Castro invited his young American audience to visit Cuba, andimplicitlyto become involved in the revolutionary spirit that was propelling social change on an island that the United States had first intervened in, and had then neocolonized and modernized, during the first half of the twentieth century.

Castros message was received enthusiastically by his audience of university students, members of a generation that was becoming aware both of the imperial role played by their country during the Cold War, particularly in the Third World, and of the civil rights disparities that cut through American society itself. However, as easily as the Cuban Revolution entered the social imaginary of this young, pacifist, libertarian, anticolonial, and antiprejudice generation, that revolution also generated fierce ideological and geopolitical disputes between 1959 and 1971.

This book explores these debates over the Cuban Revolution during the 1960s, particularly those centered on the New York public sphere and intellectual field. That decade and this city constituted a microcosm of activity whose resonance was felt around the globe. New York in the 1960s was the moment and the place for progressive movements of all kinds: artistic vanguards, womens liberation, sexual liberation, civil rights, and opposition to the Vietnam War. But these movements and struggles were also privileged scenarios for the emergence and circulation of debates over the ideological identity of Cuban socialismits truths and its errors, its coincidences and divergences from the Soviet model, its lessons for the Western Leftas well as for the articulation of critiques of US government policy toward Cuba.

The energy of the New York debates over the Cuban Revolution can be explained in part by the close economic, political, and cultural ties that came to be established between the Cuban island and the United States during the first half of the twentieth century. One result of that historical process, as Louis A. Prez Jr. and other historians have demonstrated, is that when the revolution broke out, most prominent New York media organizations, such as the New York Times and NBC, already had bureaus and correspondents in Havana whose reporting had made the island a central topic of these organizations Latin American coverage. In New York, with its strong liberal and socialist traditions, the Cuban Revolution was discussed as nowhere else, just as the Mexican Revolution and the Spanish Civil War had energized the citys public discourse decades before.

This book examines the practices of New York intellectuals who took public positions in the Cuba debate and wrote books or essays on the Cuban experience, including Waldo Frank, Carleton Beals, C. Wright Mills, Allen Ginsberg, Amiri Baraka, Susan Sontag, Norman Mailer, Irving Howe, Paul Sweezy, Leo Huberman, Paul Baran, Eldridge Cleaver, Stokely Carmichael, Jos Yglesias, and Elizabeth Sutherland Martnez. It also reexamines publications such as the Monthly Review, Kulchur, and PaLante, as well as cultural and political movements such as the Beat Generation and the Black Panthers. By means of this review of diverse social and political actors, ideologies, and aesthetics, the study seeks to map the ways in which Cuba was represented by the New York Left.

Plurality had long been a distinctive trait of New Yorks intellectual map. In the debate over the Cuban Revolution, this plurality was not merely ideological or political but was also characterized and sustained by the dissimilar identities of the subjects who participated in the debate: beat writers, hippies, Jews, blacks, Hispanics, academics, writers, and activists. Veterans of the Rooseveltian Left, such as Frank and Beals, did not see the revolution as it was perceived by young liberals like Mills or Mailer, or by young socialists like Sweezy and Baran. Even within the same currents of sympathy and solidarity with the Cuban project, different inflections and priorities can be detected, whether in the Hispanic Left of Martnez and Yglesias or the Afro-American Left of Cleaver and Carmichael.

In few cities on the planet was such a plurality of discourses on Cuban socialism generated. Echoes of the polemic were heard in Havana. For example, Pensamiento Crtico, the Cuban journal most clearly identified with critical Marxism and opposition to Marxist-Leninist hegemony of Soviet inspiration, devoted a special issue to intellectuals associated with the Black Panthers. New Yorks critical debates on the Cuban Revolution naturally had few effects, or only adverse effects, on Washingtons policies toward the Caribbean and Latin America. In fact, for all their intellectual and moral richness, the debates in question were viewed with disfavor by all the powers involved in the Cuban conflict. During the 1960s, New York once again functioned like an island in the middle of the Atlantic currents, this time those of the Cold War.

Next page