Published by Penguin Books

an imprint of Penguin Random House South Africa (Pty) Ltd

Reg. No. 1953/000441/07

The Estuaries No. 4, Oxbow Crescent, Century Avenue, Century City, 7441

PO Box 1144, Cape Town, 8000, South Africa

www.penguinbooks.co.za

First published 2015

Publication Penguin Random House 2015

Text Robin Brown 2015

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyright owners.

PUBLISHER: Marlene Fryer

MANAGING EDITOR: Robert Plummer

EDITOR: Lynda Gilfillan

PROOFREADER: Genevieve Adams

COVER DESIGNER: Jacques Kaiser

TEXT DESIGNER: Ryan Africa

TYPESETTER: Monique van den Berg

Photographs enhanced by Mark Davison using DigitalNeg

ISBN 978 1 77022 920 4 (print)

ISBN 978 1 77022 921 1 (ePub)

ISBN 978 1 77022 922 8 (PDF)

For Ailish Brown

Contents

Foreword

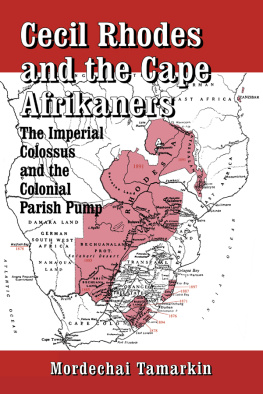

Cecil John Rhodes was a Victorian colossus, the creator of a new world. Unlike Charles Darwin or William Ewart Gladstone giants who in their own different ways set in motion the dynamism of the twentieth century Rhodes has steadily diminished in reputation as moral values have changed and his careless, perhaps unconscious and certainly in his own world entirely conventional racial prejudices have become more repugnant. None of this can lessen Rhodess achievement. Mining entrepreneur, political leader and visionary, he perceived the transformative potential of the diamond mines and gold mines of South Africa, as well as the undeveloped grasslands of its distant central African horizon what would become, and then cease to be, Rhodesia. Though it was only after his time that the disparate settler communities of the southern extremity of the continent would merge into the Union of South Africa, his vision made it the powerhouse of modern Africa, the generator of the wealth which would attract migrants of all races, from other parts of Africa, from India, and from Europe. The social disruption and the injustices which followed were not his doing, though they may have been the inevitable consequences of his vision. In any case, he has been made to take the blame for them.

However, the vision of Cecil Rhodes transcended even this. His own version of the civilising mission of the white races involved a future federation of the English-speaking peoples, starting with the British Empire and its dominions, but eventually, he hoped, reincorporating the United States. Germany would perhaps be an honorary member. The Anglosphere, in modern parlance, combining physical strength with moral leadership, would guide the rest of the world in the march of progress and civilisation.

Rhodes was a practical man as well as a visionary, and at quite an early stage of his career he gathered round him a group of close friends who shared his enthusiasm, and who were to be entrusted after his death with the funds to take his plan further. The first step was the establishment of the Rhodes Trust and the recruitment of the first Oxford Rhodes Scholars, who, he believed, would be an Empire-wide fraternity and the future leaders of the English-speaking peoples. The Rhodes Trust is with us still, and Rhodes Scholars have distinguished themselves throughout and beyond the Anglosphere. The long shadow of Rhodess coterie, transformed into Milners Kindergarten and other avatars of the founders spirit, lies, arguably, over the whole twentieth century.

In this book, Robin Brown traces the emergence of the Rhodes circle, interweaving it with his own experiences of travelling through Africa and growing up in Rhodesia. He has put together a very diverse and widely scattered body of evidence, from which Rhodes himself appears as a much quirkier and more contradictory figure than either his admirers or his detractors have allowed. In the following pages, with a deep knowledge of the many landscapes of southern Africa and a profound and sympathetic understanding of its various peoples, he has been able to put Rhodess turbulent life and persistent vision into a realistic context, and, further, to trace his surprisingly far-reaching legacy through the twentieth century into our own time. Not every reader, I suspect, will agree with all his inferences on the long reach of the Secret Society; some will doubt its coherence and its sense of identity; there is room for more than one view. But every reader who persists will find here a fascinating story and a stimulating argument which raises important questions, not only about the past two centuries but about the present time.

JEREMY CATTO

FORMER RHODES FELLOW AND TUTOR IN MODERN HISTORY, ORIEL COLLEGE, OXFORD

Prelude

There came a sudden conjunction of two meteors, perhaps in the little hut that Gordon had been allocated under the shadow of the northern mountains of what, much later, was to become Lesotho. Or, to give a romantic interpretation to this encounter: Rhodes and Gordon, lonely men of misogynist impulse, both being absorbed in [their] gigantic dreams, were delighted to find each other Rhodes and Gordon went on long walks together during what must have been a period of no more than a week In 1881 Gordon wrote a letter to a young member of Parliament proposing a kind of secret community of men for the betterment of society a group of ombudsmen in Britain modeled on the so-called College of Censors in China.

Robert I. Rotberg, The Founde r : Cecil Rhodes and the Pursuit of Power

On the 19th September, 1877, this youth of 24 wrote his Last Will and Testament To and for the Establishment, Promotion and Development of, a Secret Society, the true aim and object whereof shall be the extension of British rule throughout the world. Much later in life Rhodes remarked to me that he had never deviated from the policy he then laid down in that shanty on the Diamond Fields.

Sir Lewis Michell, The Life and Times of the Right Honourable Cecil John Rhodes 1853 1902 , Vol. 1

* * *

The conjunction of these two meteors the Colossus of Africa, Cecil John Rhodes, and Charles George Gordon, also known as Chinese Gordon of Khartoum heralded a new era: it not only changed the way Britain was governed, but also how it fought its wars and ruled its Empire and Commonwealth over the next century.

Together, Rhodes and Gordon planned to establish a secret society which would be ruled according to pseudo-Jesuit disciplines. In this way, the seeds Gordon had planted with a young member of Parliament named Reginald Baliol Brett took root. For years, Gordon had corresponded with this courtier and royal whisperer, exchanging views about the Empire.

After discussions with Brett in London in 1891, Rhodes paid Bretts friend, newspaper magnate W.T. Stead, a huge advance to help set up the Secret Society. In time, W.T. Stead became Rhodess trustee, administering his vast diamond and gold fortune. He was assisted in this task by the former prime minister Lord Rosebery and the banker Nathan Rothschild.

In 1885, Gordon was slain by the Mahdis forces after being besieged in Khartoum. Seven years later, in 1902, Rhodes went to his lonely grave in the remote hills of a country the size of France which he had named Rhodesia. By then, however, he had entrusted the stewardship of the Secret Societys affairs to a former colleague of Steads named Alfred Milner, who was a political proconsul in South Africa. As Lord Milner, he soon held a seat on the Queens Privy Council and later served as Britains minister of war, eventually developing the Secret Society into a global political network.

Next page