Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

Blue Rider Press is a registered trademark and its colophon is a trademark of Penguin Random House LLC

Names: Weingarten, Gene, author.

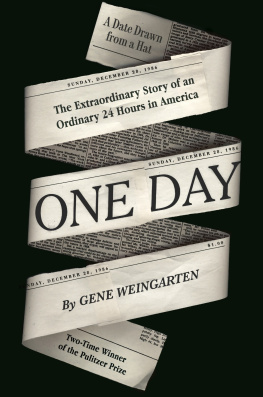

Title: One day : the extraordinary story of an ordinary 24 hours in America / Gene Weingarten.

Description: New York : Blue Rider Press, 2019.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019001936 | ISBN 9780399166662 (hardback) | ISBN 9780698135598 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: United StatesSocial conditionsAnecdotes. | United StatesSocial life and customsAnecdotes. | United StatesBiographyAnecdotes. | BISAC: HISTORY / United States / General. | SOCIAL SCIENCE / Sociology / Urban. | POLITICAL SCIENCE / Public Policy / General.

While the author has made every effort to provide accurate telephone numbers, Internet addresses, and other contact information at the time of publication, neither the publisher nor the author assumes any responsibility for errors, or for changes that occur after publication. Further, the publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

Introduction

To see a World in a Grain of Sand,

And a Heaven in a Wild Flower,

Hold Infinity in the palm of your hand

And Eternity in an hour

W ILLIAM B LAKE , Auguries of Innocence

At 2:05 P.M . on Thursday, December 13, 2012, I sent an email to Tom Shroder, my friend and editor. It said, in its entirety: I wonder what happened on May 17, 1957.

The phone rang. It was Tom. Thats a good idea, he said.

If it doesnt sound like an idea to you, much less a good one, its because you lack context. Tom and I were forever bouncing off each other ambitious concepts for our next book. We usually trashed them, for kindness sake.

Between us, Tom and I had written seven books, only two of whichone apiecehad even approached commercial success. The business model for the book publishing industry resembles the business model for nineteenth-century oil-well wildcattersthat is to say, it is an economy of informed guesswork. Most books are financial failures, but the rare hit becomes a gusher and underwrites all the dry holes. This may keep the publishing industry afloat, but it wreaks hell on writers egos. With book ideas, friends dont let friends get too enthusiastic.

But Tom liked this idea and understood it implicitly. Select an ordinary day at random, report it deeply, then tell it like it happenedfrom midnight to midnight, the most basic, irreducible unit of human experience. Ideally, the more youd learn, the more firmly youd establish that in life, theres no such thing as ordinary. Also, that in the events of a single dayin that telltale grain of sandyou would find embedded in microcosm all of the grand themes in what hacks and academics tend to call The Human Experience.

It was a stunt, at its heart. But I like stunts, particularly if they can illuminate unexpected truths. The magazine story for which I am best known involved placing Joshua Bell, the renowned violinist, outside a Metro stop in downtown Washington, D.C., at rush hour, incognito. In jeans, a polo shirt, and a baseball cap, for three-quarters of an hour on his priceless Stradivarius, Bell played timeless music, masterpieces by Bach and Schubert and Massenet, with a violin case at his feet, open for handouts, seeded with petty change. Would anyone notice the extraordinary beauty that was happening twenty feet away?

Few did. Most people hurried by, as if the fiddler in the subway were a nuisance to be avoided. What happened that day became a story not about our taste and sophistication but about our priorities: Have we so overprogrammed our lives that it is impossible to experience unscheduled awe? How many other worthy things are we racing past?

The stunt of reporting an ordinary day would also test a journalistic conceit I embrace: That if you have the patience to find it and the skill to tell it, theres a story behind everyone and everythingthat although great matters make for strong narratives, power also can lurk in the latent and mundane.

As the Sunday features editor at The Washington Post, I once assigned five writers to each hammer a nail into the phone book and do a profile of whomever the nail stopped at. It was a wild stab, literally, and it hit a vital organwe got five compelling stories. One Christmas I summoned four of the best writers at the Post and sent them off in different directionsone north, one south, one east, one west, with instructions to walk no farther than seven blocks and bring me back a good Christmas story. If you dont find one, I said, you may as well not return. They all came back, and collectively they pulled off a Christmas miracle.

The most important book of my teenaged years, the one that really changed the way I thought about things, was Flatland, an obscure 1884 work of science fiction and social satire written by an unassuming English schoolmaster and theologian named Edwin Abbott Abbott. The man with the eccentric name wrote what may well be the most eccentric book of his generation, a slender, crudely illustrated novella set in a two-dimensional world inhabited by sentient geometric figures.

The narrator, a square, is visited one day by a sphere. Initially, the square sees this three-dimensional being only as a circle of rapidly changing diameter. This is because a sphere, arriving from above and descending into and through the two-dimensional plane in which the square lives, would fluctuate in circumference depending on the diameter of the portion of the sphere that happens to be intersecting the flat plane, as a circle, at any particular moment. (There will be no more math.)

The sphere is received as something of a deity. He has selected the square to be his disciple and prophet. He would show the square the existence of a third dimension, and then send him back to his land to spread the news as gospel. Thus the sphere elevates the square above Flatland into Spaceland, so he can look down and see his circumscribed, unlovely world with disturbing new claritya despotic, socially rigid, class-obsessed aristocracyeven further diminished by the startling knowledge of an entirely new, seemingly limitless dimension of existence.

Back in Flatland, the squares excited vision of Spaceland seemed to others not like science but like faith, since such a thing could not be demonstrated or even adequately explained within the context of a two-dimensional world. In the end, the square was punished for his insights because they challenged accepted dogma. He was Galileo, but he did not bend. He became a martyr for truth.