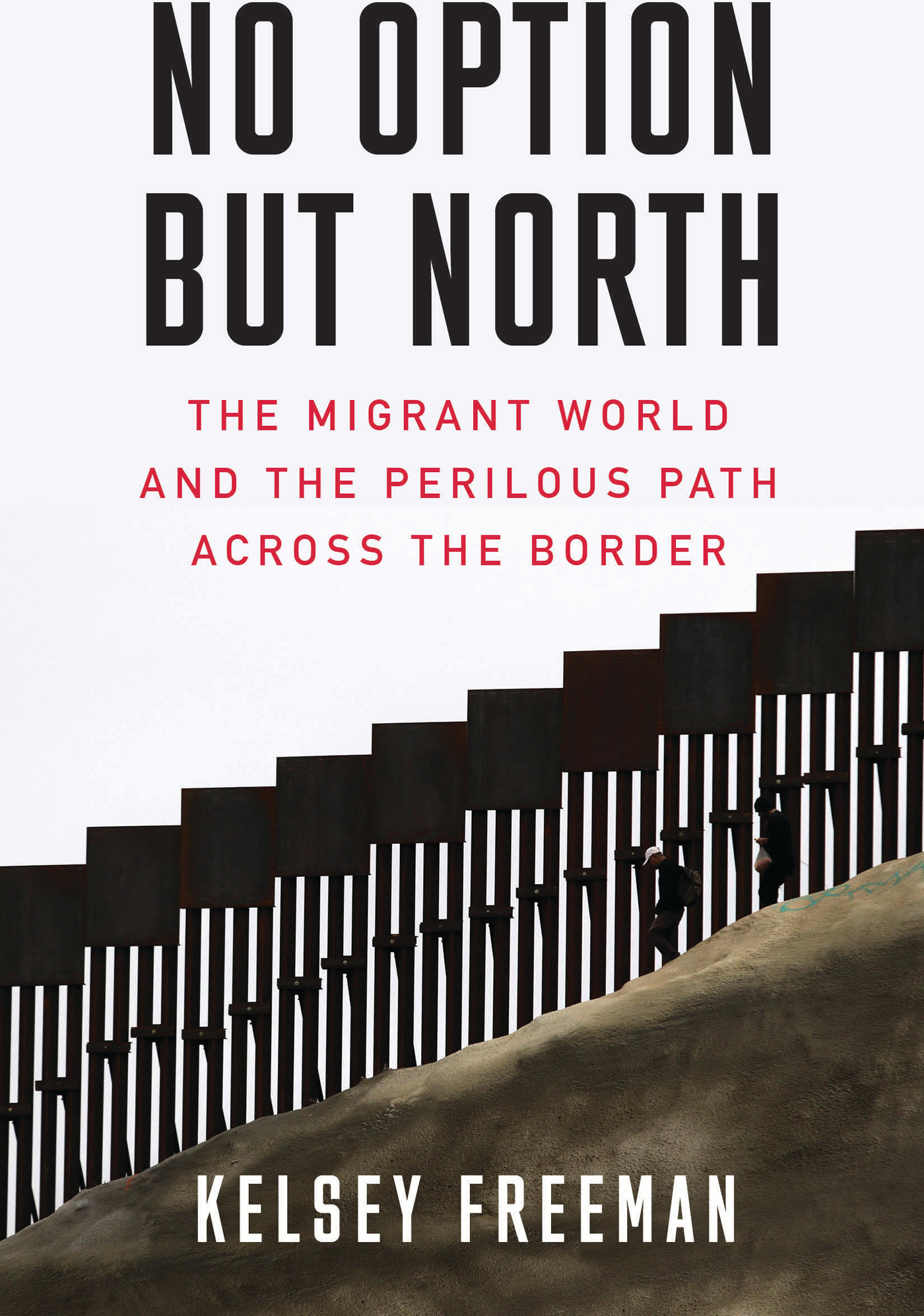

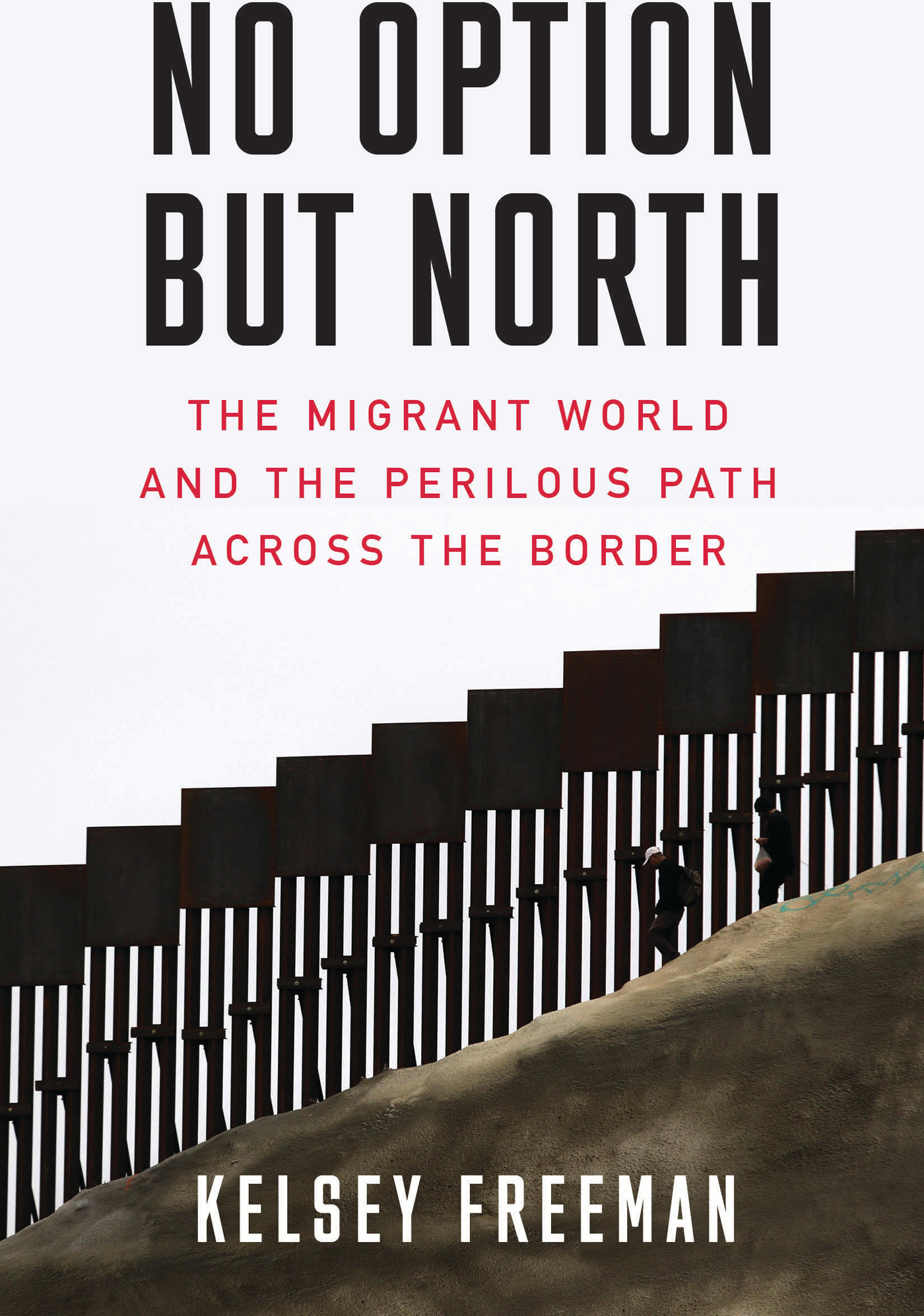

NO OPTION BUT NORTH

The Migrant World and the Perilous Path across the Border

Kelsey Freeman

Photographs by Tess Freeman

Copyright 2020 by Kelsey Freeman.

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner with-out written permission of the publisher. Please direct inquires to:

Ig Publishing

Box 2547

New York, NY 10163

www.igpub.com

ISBN: 978-1-632460-98-1 (ebook)

For Nonna,

who first told me her migration story at bedtime

and who became my unwavering cheerleader.

CONTENTS

PART ONE

POR NECESIDAD

PART TWO

THE PRIVILEGE TO CROSS THE BORDER LEGALLY

PART THREE

TWENTY THOUSAND LEAGUES UNDER THE MIGRATION SEA

PART FOUR

BECAUSE POWER MATTERS

PART FIVE

LEAVING THE SHELTER, COMING HOME

Migrants await their next move at El Refugio.

Mara, age three, passes the time at Celayas long-term shelter, El Refugio.

Folkrico dancers gather backstage before a performance in Quertaro.

INTRODUCTION

THE DETAILS WERE ALWAYS OVERWHELMING. I would do my best to take it all in, to feel the emotional force of each story as if it were the very first one Id ever heard. But in the end, there were no words to describe the grown man crying in front of me, or the many others like him who shared their suffering. His tearstheir tearsembodied the anguish inflicted upon all those who migrate north, making the choice that really isnt a choice at all.

Back in the United States three years later, I see the same tears in a Mexican-American student as he painfully describes his journey across the Rio Grande. People just dont get it, he laments as we speak behind a podium after a lecture. Its been over a decade since he crossed, but the trauma of the journey still lives within him. His tears stretch through time and space to join with each grown man that cried in the desert, cried as he said goodbye to his children, cried at the rape of the woman beside him. His tears were the same as all those who said Si Dios quiere (God-willing) before attempting the journey for the fifth or sixth time. As he wiped his tears aside and swallowed, he exemplified everyone else before him that buried the hurt and just kept going.

In thinking of all the words to describe the world of migrationa complex, violent geographic path north from Mexicos southern border to the United Statesperhaps the best image is simply tears.

The author on her daily commute to teach English at the university where she worked in Celaya.

In January 2016, six months before I would return to Mexico to study migration, I was traveling in the highlands of Chiapas, winding over roads that appeared as if they were scribbled atop the mountainous landscape. This combi ride was research for my undergraduate thesis, which focused on the development of two Indigenous social movements in Latin America (including the Mexican Zapatistas). My thesis explored Indigenous peoples in Mexico who had chosen autonomy while rejecting the oversight of government systems. Yet in pursuing this research, I felt a persistent tug in another direction. What about the many Mayan farmers who had abandoned Mexico altogether? What happened to those who had lost their livelihoods and headed north? It was impossible to separate the study of Indigenous rights from the underlying pull of migration.

During that combi (a converted microbus that is part of the public bus system), ride, I sat next to an old man with a large gummy smile and rough campesino hands. He alternated fluidly between Tzotzil (a Mayan language) and Spanish as he chatted with his compaeros. Eventually he turned to me, sharing a story about how he used to live in Southern California with his family. He recounted the difficulties of living in a foreign place, the exhausting nature of agricultural labor, his frustrating attempt to learn a third language. At least, he sighed, he had been with his family.

Then he spoke of being deported. His sun-kissed wrinkles grew more pronounced as his face scrunched with sorrow. Desesperacin, he called it. Leaving his family behind some intangible, distant barrier was the essence of despair.

As we approached my destination, my new acquaintance posed a critical question: How was it that I could visit his country to do research for two weeks, when he had been repeatedly rejected for a visa to see his family in my country? It was not a malicious inquiry, nor one intended to induce guilt. He simply wanted to make sense of a system that had blocked his opportunities and separated him from his family, yet still allowed me to casually visit to study his people.

This question lingered with me. I knew that being from the United States afforded one enormous privilege. Until that moment in the combi, however, I could not start to grasp how thoroughly the cards were stacked against migrants like my traveling companion. His question sparked others: What does it mean to have or lack power while migrating? How do factors like migrants race, class and nationality affect the legal options available to them? Was my friend on the bus unable to get a visa because he was a poor Indigenous farmer from Mexico?

I became determined to unravel the human element underlying the current state of immigration by examining it, as best I could, from the inside out. In late summer of 2016 (in the thick of the Donald Trump presidential candidacy), I left on a Fulbright grant to teach English at a university and study migration in the industrial city of Celaya, Guanajuato in Central Mexico. Two weeks into my stay, I found the local migrant shelter, became a frequent visitor, and spent much of the next year interviewing the array of travelers who passed through. I also immersed myself in Celaya, a city that lived and breathed migration and was about halfway through the perilous route north.

Like many, I had read countless stories about the human traffickers known as coyotes (or polleros) and the numerous dangers of crossing the US border. I wanted to delve deeper, however, by exploring the often-cyclical experiences that migrants encounter before they even reach the vast desert that serves as border territory. Meeting migrants in Celaya allowed me to witness the intense weight of the journeyhardships burdening their hunched shoulders and anxieties about the upcoming border coloring their faces.

I choose specifically not to accompany migrants as they headed north, avoiding the sort of immersion journalism that pretends that observing the migration phenomenon doesnt affect it. I am uncomfortable with stories that portray migrant journeys as a form of extreme adventure for the writer, one that they inevitably escape with a goodbye and a passport. In my conversations with migrants, I developed a comfort with identifying the power imbalance between us, rather than pretending to be under the same circumstances. While I have included many of my own stories and observations in this book, I have sought to do so in way that serves as a prism into the systemic obstacles in immigration that a white, American woman like myself will never face.

Next page