Preface to the Second Edition

The first edition of this book was published one year before the terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon. On September 11, 2001, the book was both instantly out of date and more relevant than ever. It was dated in that terrorism became the new anxiety-provoking issue in the politics of borders and border controls. And yet the books relevance endured in that border policingalong the U.S.-Mexico line and elsewherebecame an even more high-profile and high-drama activity, with the enforcement efforts of the 1990s further accelerating and expanding during the first decade of the twenty-first century. As it turns out, the escalatory dynamics in immigration and drug control traced in this book were merely a warm-up for a yet more intensive, expansive, and high-maintenance border game in a new security environment. And the escalation continues, with no end in sight.

Much of this recent escalation, it should be emphasized, has involved repackaging preSeptember 11 border control ideas and instruments as new antiterrorism programs and initiatives. This has included the growing use of new surveillance and information technologies (creating virtual borders) and extending border controls outward (a thickening of borders). Yet even as border enforcement agents are now careful to publicly declare terrorism to be public enemy No. 1 and their top target and priority, in their day-to-day on-the-ground activities they continue to be largely preoccupied with policing unauthorized cross-border flows of migrant workers and drugs. However, adding counterterrorism to an already ambitious and overextended border control agendanow integrated under the broad new label of homeland securityhas upped the ante, creating a fresh source of border anxiety and further securitizing and hardening the policy discourse about borders and border policing.

This second edition of the book leaves the contents of the first edition intact, but it includes a new afterword that provides much needed updating, with a particular focus on the impact of September 11 and its aftermath.

PETER ANDREAS

Providence, Rhode Island

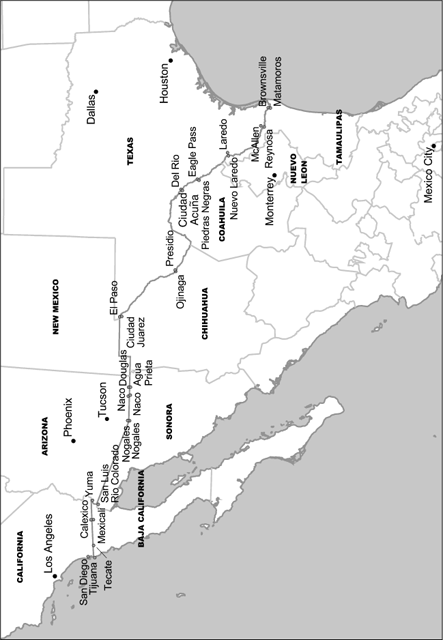

The U.S.-Mexico border

Preface

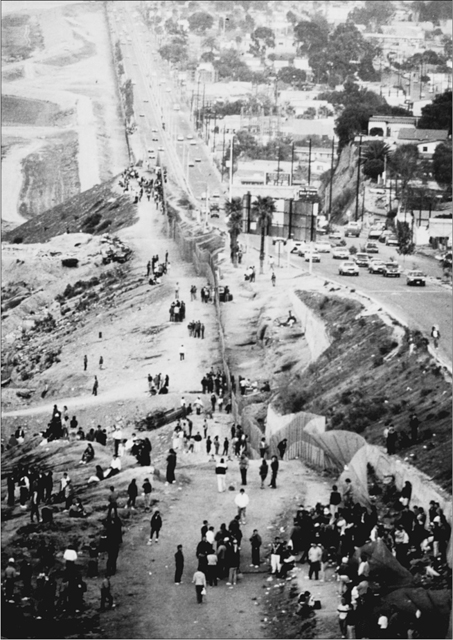

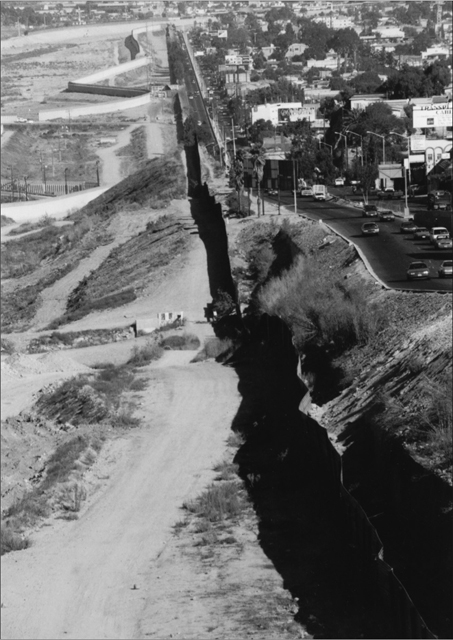

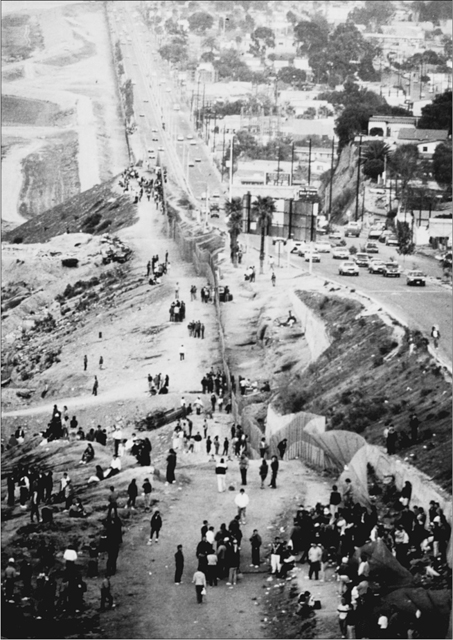

Standing inside the front entrance of the public affairs office at the Border Patrols sector headquarters south of San Diego not long ago, I immediately noticed two large photographs prominently displayed on the wall. They show the same stretch of the California-Mexico border, historically the single most popular crossing point for illegal migrants heading north. The first photograph, taken in the early 1990s, shows a mangled chain-link fence and crowds of people milling about, seemingly oblivious that the border even exists. The Border Patrol is nowhere in sight. The image is of a chaotic border that is defied, defeated, and undefended. The second photograph, taken a number of years later, shows a sturdy ten-foot-high metal wall backed up by lightposts and Border Patrol all-terrain vehicles alertly monitoring the line; no people gather on either side. The image is of a quiet and orderly border that deters and defends against illegal crossings. The new wall was built by U.S. Army reservists out of 180,000 metal sheets originally made for temporary landing fields during military operations. Mexicans have dubbed it the Iron Curtain.

These sharply contrasting pictures are part of a larger transformation in the policing of the nearly 2,000-mile-long U.S.-Mexico boundary. In a relatively short period of time, border control has changed from a low-intensity, low-maintenance, and politically marginal activity to a high-intensity, high-maintenance campaign commanding enormous political attention on both sides of the territorial divide. Reflecting the new enthusiasm, the size of the U.S. Border Patrol has more than doubled since 1993. An advertising agency has even coined a catchy slogan to woo thousands of new recruits: A career with borders but no boundaries. The border enforcement role of many other federal agencies has also expanded at a rapid pace. The buildup, moreover, is not restricted to the U.S. side of the line. The Mexican military, for example, has been placed in charge of the antidrug effort in many of the countrys northern states.

People mingle around broken-down border fence, about one mile west of the San Ysidro port of entry, San Diego-Tijuana border, 1991. (Photo courtesy of the U.S. Border Patrol.)

New fence, about one mile west of the San Ysidro port of entry, San Diego-Tijuana border, 1999. (Photo courtesy of the U.S. Border Patrol.)

What explains the sharp escalation of border policing? That is the underlying question of this book. It is particularly intriguing because the tightening of border controls has happened at a time and place otherwise defined by the relaxation of state controls and the opening of the bordermost notably through the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). Noticeably left out of NAFTA are two of Mexicos most important exports: illegal drugs and migrant labor. Instead, tariffs on these smuggled goods (or bads, depending on ones perspective) are rising in the form of more intensive policing. The result has been the construction of both a borderless economy and a barricaded border. The politics of opening the border to legal economic flows is closely connected to the politics of making it appear more closed to illegal flows. I argue that the escalation of border policing has ultimately been less about deterring the flow of drugs and migrants than about recrafting the image of the border and symbolically reaffirming the states territorial authority. Those who view border enforcement as either puny and ineffective or draconian and inhumane too often fail to appreciate its perceptual and symbolic dimensions.

Indeed, border policing has some of the features of a ritualized spectator sport, but in this case the objective of the game is to tame rather than inflame the passions of the spectators. Calling it a game is meant not to belittle or trivialize border policing and its consequences but rather to capture its performative and audience-directed nature. The game metaphor also draws attention to the strategic interaction between border enforcers and illegal border crossers. It provides a healthy antidote to the metaphors of war and natural disastersuch as invasion and floodmore commonly used to characterize the problems of immigration and drug control.

The U.S.-Mexico boundary is the busiest land border in the world, the longest and most dramatic meeting point between a rich and a poor country, and the site of the most intensive interaction between law enforcement and law evasion. Nowhere else has the state been so aggressively loosening and tightening its territorial grip at the same time. Nowhere else do the contrasting state practices of market liberalization and criminalization more visibly overlap. It was these provocative features that initially captured my attention. A comparative perspective, however, suggests that while the U.S.-Mexico border is unusual, it is by no means unique. Other meeting places between rich and poor countries, most obviously the eastern and southern external borders of the European Union, show similar dynamics. Framing the study more broadly reveals that within a general escalation of law enforcement, different forms and trajectories of escalation reflect distinct historical legacies and regional political and institutional contexts.