CHARLES D. THOMPSON JR.

BORDER ODYSSEY

Travels along the U.S./Mexico Divide

UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS PRESS

AUSTIN

Copyright 2015 by the University of Texas Press

All rights reserved

First edition, 2015

Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work should be sent to:

Permissions

University of Texas Press

P.O. Box 7819

Austin, TX 78713-7819

http://utpress.utexas.edu/index.php/rp-form

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Thompson, Charles D., Jr. (Charles Dillard), 1956 author.

Border odyssey : travels along the U.S./Mexico divide / Charles D. Thompson, Jr. First edition.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-292-75663-2 (cloth : alk. paper)

1. Mexican-American Border Region. 2. United StatesForeign relationsMexico. 3. MexicoForeign relationsUnited States. 4. Thompson, Charles D., Jr. (Charles Dillard)Travel. I. Title.

F787.T47 2015

972'.1dc23 2014031549

doi:10.7560/756632

ISBN 978-0-292-77199-4 (library e-book)

ISBN 978-0-292-77200-7 (individual e-book)

For the border crossers.

For the monarchs.

For my parents.

For Hope.

Something there is that doesnt love a wall

That wants it down.

ROBERT FROST, MENDING WALL (1913)

Mr. Gorbachev, tear down this wall.

PRESIDENT RONALD REAGAN, BERLIN, 1987

Complete the danged fence.

SENATOR JOHN MCCAIN, ARIZONA, 2010

Yea, though I walk through the Valley of the Shadow of Death, I will fear no evil.

PSALM 23:4 (KJV)

CONTENTS

ONE

Evidence of Things Not Seen

CIUDAD JUAREZ, SONORA, MEXICO

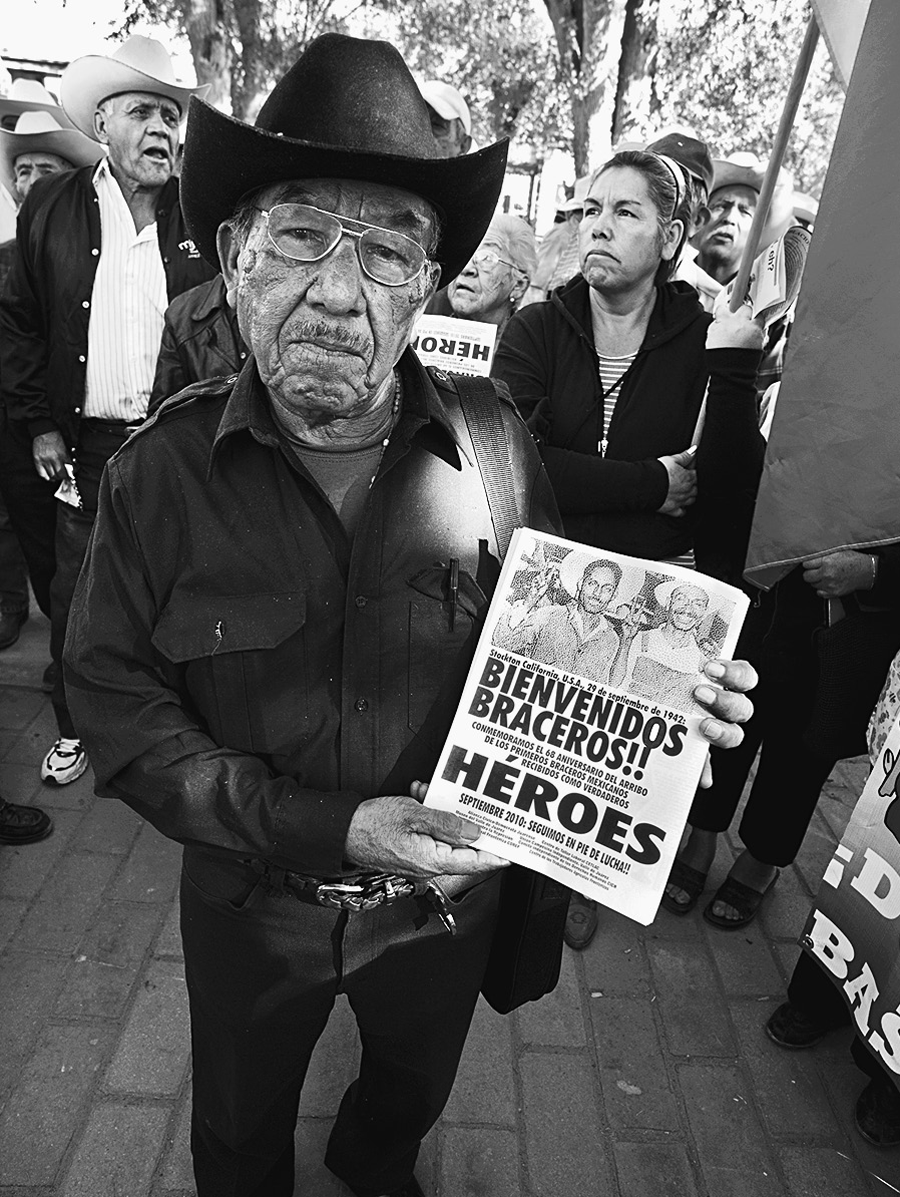

NEARLY TWO HUNDRED PEOPLE, NONE OF THEM YOUNGER THAN seventy-five, crowded around us. My wife Hope and I had accompanied our friend Poncho to visit these Braceros on a Sunday morning in Benito Juarez Park in Ciudad Juarez, Mexico. When I asked if I might take some photos of themregular candid shots is what I had in mindthey began moving toward us, surrounding us, getting so close that each individual face filled the frame. They formed a line with each one waiting his turn, each set of eyes asking that I not leave anyone out. They had me for the entire morning.

Years earlier they had been given visas and invited to work in the United States. Our country had asked them to come because we needed their strong arms. In 1942, officials began a federal program to import these laborers, calling them Braceros. They came as replacements for our soldiers and factory workers during the Second World War, and they remained as field hands after the war. The program lasted until 1964. During its twenty-two years some 4.6 million men signed contracts and traveled north of the border to work. After 1964, the United States no longer needed them and told them to go home. There was no letter of thanks, and government officials said they would send their retirement money later.

The Braceros had waited patiently, trusting they would be paid the benefits they had earned. But now they were old and no retirement checks had arrived. Half a century had passed. They were demonstrating in the park because they wanted the world to know they were still waiting. They seemed gratified that someone, anyone, would be willing to document their presence in this park.

As I looked through the camera lens at their lined faces, I imagined them all as young farmworkers. They had been faithful in giving some of their best years to work in our fields. Now too old to work, they had gathered in this park every Sunday for years. They had pledged to one another to continue until they were too old even to do that. The ones still able to continue stood together peacefully once a week a few miles from the U. S./Mexico border, calling attention to the injustice of it all.

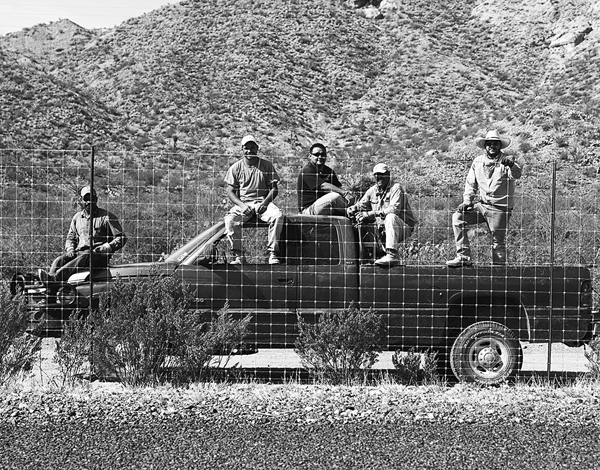

The day we arrived in 2010, the old Braceros held signs and propped placards on a nearby fence, while one hoisted a Mexican flag. They stood strong, shoulder to shoulder, an unlikely group of protesters: old men in cowboy hats and caps with various logos. They stood silently; there were no chants. Alongside them were some family members: wives, widows, and a few supporters, including a faithful retired professor named Manuel Robles who helped them stay organized. Now I held each of them in my frame, and for the briefest of moments each gazed back, his face telling volumes.

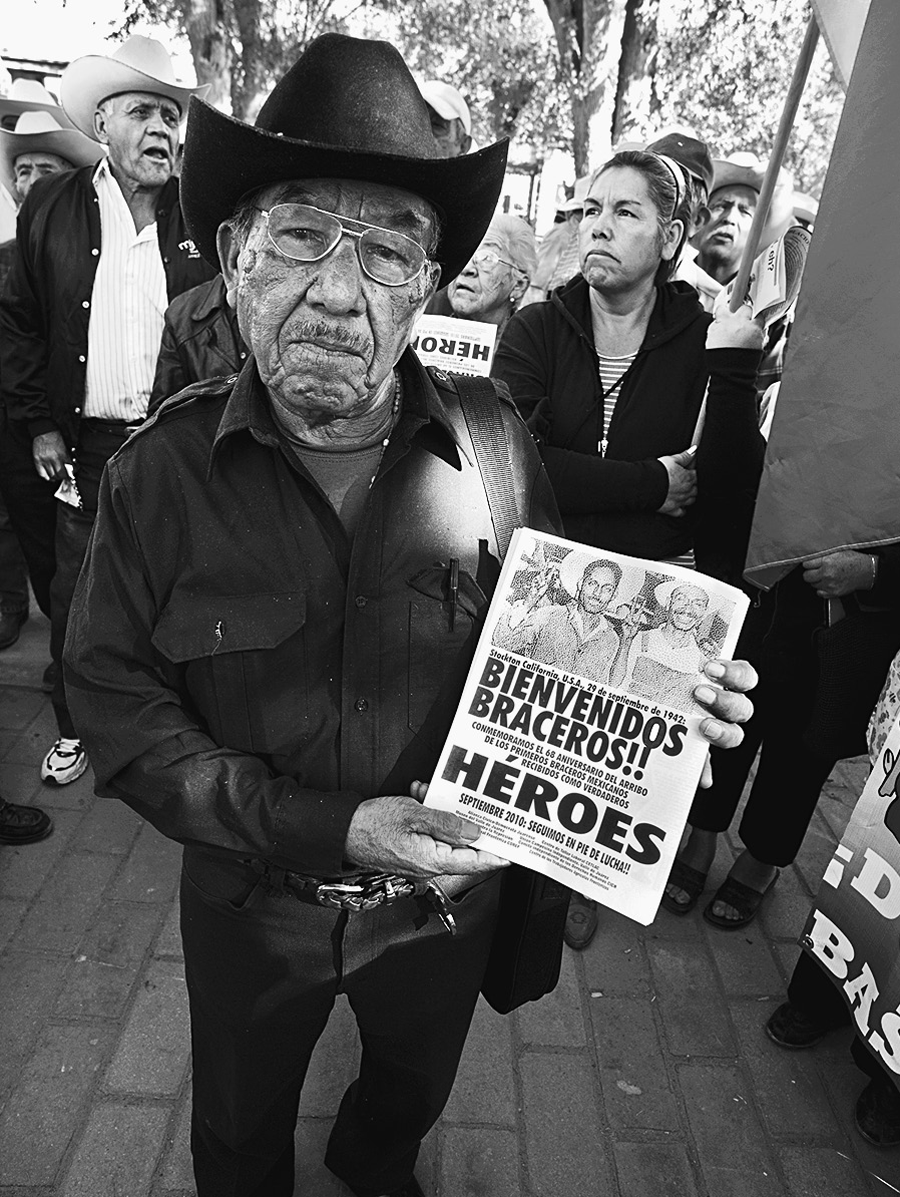

Modesto Zurita Estrada, just one of the heroes at the Braceros Sunday gathering in Ciudad Juarez.

Occasionally over the years a reporter from Mexico had happened by to write an article. During election season a politician or two had sometimes discovered them again. That day they stood in line waiting their turn to stare into my lens as if this alone could rescue them from the grasp of anonymity. Their faces were like road maps, with lines of experience from crisscrossing the border and working in the sun written on their skin. I focused and clicked away, asking Hope to write down their names alongside descriptions in my notebook. White cowboy hat; red checked western shirt, I said aloud as I snapped the shutter. Black Marlboro cap, glasses, green striped shirt. We would match the descriptions with the names and photos later.

I noticed that some held up laminated cards and photocopies of papers in their photos. They were copies of decades-old identification cards and work visas showing they had entered the United States legally. These pictures were of proud men in their twenties, all of them ambitious farm people dressed up and staring solemnly into the camera just before they left for the U.S. Were these the last portraits some of them had taken before now? Some had died, and their names were on a banner propped up temporarily at the Jurez statue. The remaining ones were like veterans of a forgotten war who knew their ranks were dwindling.

I had to tell them I possessed no official means to help them. I stepped onto a park bench and projected my voice above the crowd encircling me, speaking in Spanish and offering them as much respect as possible. Ladies and gentlemen, I want you to know that Im not with the United States government. But even as I said that, I realized that as a citizen, I did in fact have some accountability in thisas every American has. I knew I didnt want to give them false hopes, though I didnt want to shirk my responsibility either. I continued, I teach at a university in the U.S. and my wife and I are here at the invitation of our friend, Professor Luis Alfonso Herrera Robles from the University of Juarez. Poncho, as he is known to his friends, is a sociologist who for years has been going to the park, first with his parents to serve coffee and pan dulce, and later working with his mentor Professor Robles to record their stories on tape and to document their cause. Poncho believed my photographs could help and had told this to the Braceros. Poncho and I had talked before we arrived of collaborating on a photo and oral history project, one that we have since pursued and finished. But I knew in the Braceros presence that day that my work was a long way from getting their money for them.

Its so important that you are here, I announced in my strongest voice. Its an honor for my wife and me to stand with you here today and to join with you as you demand justice. We will try our best to spread the word about you and use the photographs to help. We hope to bring copies back to you as well. Please continue your struggle for what you know is right.

Next page