About the Author

Jessica Wapner is a journalist and former science editor at Newsweek whose work has appeared in The New Yorker, The New York Times, Wired, Medium, Discover, Popular Science, Self, Scientific American, New York magazine, The Atlantic, and elsewhere. Her first book, The Philadelphia Chromosome, was named a top ten nonfiction book by The Wall Street Journal. She lives in Brooklyn.

jessicawapner.com | @jessicawapner

Thank you for purchasing this ebook.

Join our email list to learn about new releases, ebook deals, bonus content and more from The Experiment.

Join

[eepurl.com/cO86ZH]

You can also connect with us on:

Facebook

/experimentbooks

Twitter

@experimentbooks

Pinterest

/theexperiment

We hope you enjoyed Wall Disease.

Dont miss Jessica Wapner's other book, The Philadelphia Chromosome, available now

Continue reading for an exclusive excerpt!

| PRELUDE |

Down to the Bone

February 2012

G ary Eichner sat in a chair backed up against a wall. Across the room, his nurse was half hidden by a computer. She scrolled through his medical chart on a monitor he couldnt see, typing his responses to her questions. He answered and smiled as if he were just fine, as though that would somehow make it so. He kept his worry concealed, silently wondering what the next hour would reveal about the disease that had so suddenly overtaken his life. Fear permeated his every thought.

The nurse ran through the litany of side effects that he might be experiencing from the leukemia medication hed recently begun to take. Any chest pain? she asked. Heart problems? Any swelling in your ankles? Any problems with nausea?

Eichners blanket no was tempered only by his description of what happened when he took the drug on an empty stomach. Its massive cramping, massive pain in the stomach, he told the nurse. Its just like the worst thing youve ever had.

The nurse knew that Eichner really had no idea of the worst thing someone with his type of leukemia could have. Few patients with Eichners disease today will ever know that kind of pain.

But if the nurse was thinking anything of the sort, she kept it to herself. After all, her patient was about to have a large, hollow needle inserted into his bone so that his doctor could extract a sample of his marrow. Having witnessed countless such procedures during the twelve years shed been a nurse to patients taking the drug, she knew how much was riding on this biopsy, and she knew that Eichner, age 43, was well aware that his life was at stake.

If anyone could set him at ease about that, it was his doctor, Brian Druker. All I care about is that youre making some progress, Druker told his patient, who had come to Drukers clinic in Portland, Oregon, for a bone marrow biopsy. The procedure would reveal whether the medicinea pill hed been taking daily for six monthswas tackling the leukemia that had invaded his body. Eichner had chronic myeloid leukemia, or CML, a cancer of the white blood cells that, though slow growing, could be fatal. I will be happy if youre eighteen out of twenty. Eichner nodded his understanding, his jittery foot the only sign of his nervousness.

For Eichner, those numbers were part of the new language hed learned since his diagnosis in the summer of 2011. As with so many cancer diagnoses, the education began suddenly and unexpectedly. After a day or so of sharp, excruciating kidney pain, Eichner, a single parent of a teenage boy, drove himself to the emergency room at his local hospital in Olympia, Washington, where hed been living at the time. His sister-in-law, a trauma flight nurse, had told him she thought he had kidney stones, so Eichner was expecting to be admitted for a standard, albeit painful, procedure. But when several doctors walked into his hospital room together, he knew something wasnt right. You dont have kidney stones, they told him. Youve got what we believe is leukemia.

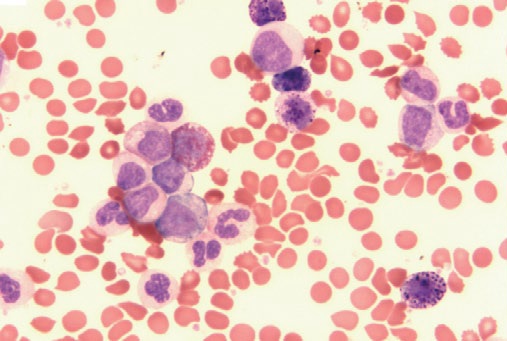

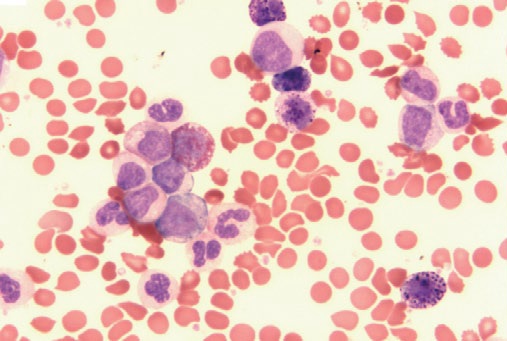

A blood test soon revealed that Eichner, in otherwise perfect health, had CML. The excess number of white blood cells contained in the sample confirmed that much. The doctors explained that the stabbing pain hed thought came from his kidneys probably was from his spleen, enlarged by the high concentration of leukemia cells within. Although the slow-moving nature of the disease meant he wasnt in immediate danger, there wasnt any time to lose. For the best chance at long-term survival, he needed to start treatment right away.

A sample of blood from a patient with CML. The excess abnormal white blood cells that are the hallmark of this disease are stained purple. Credit:

Hematologic and cytogenetic (FISH) responses to CML: Republished with permission of the American Society for Clinical Investigation, from Applying the Discovery of the Philadelphia chromosome, Daniel W. Sherbenou and Brian J. Druker, Journal of Clinical Investigation,

Volume 117, Issue 8, 2007; permission conveyed through Copyright Clearance Center, Inc.As Eichner was rapidly informed, danger could eventually come. If the treatments didnt work, within five years his bone marrow would fill with blast cells, white blood cells that fail to mature and thus are both overly abundant and thoroughly useless. His blood, once free flowing, would turn into viscous sludge. The supply of iron-rich red blood cells that carry oxygen around the body would steadily plummet, leaving him fatigued and anemic, while a decrease in the number of platelets would render his blood unable to clot. As the disease moved from the accelerated phase (more than 15 percent blast cells) to blast crisis (more than 30 percent blast cells), the minuscule capillaries leading to his eyes and brain would clog. His spleen would likely become profoundly enlarged. As his body began shutting down, he would bleed in his brain, in his intestines, and out of every orifice.

Two days later, Eichner was having his first bone marrow biopsy, performed by a nurse who spoke broken English and had to climb on top of Eichner to hammer in the four-inch-long needle to break through his bones, which had become hardened and inflamed from the profusion of white blood cells inside.

Finally, she managed to extract an ounce of marrow, the spongy matter in the center of our bones where new blood cells are made. In the genetics laboratory, a fluorescent dye applied to the coiled strands of DNA inside Eichners blood cells revealed the telltale sign of CML: a genetic mutation known as the Philadelphia chromosome, an abnormal chromosome regarded as the defining feature of this fatal, spontaneously arising cancer and discovered more than fifty years ago. Twenty out of twenty cells in a sample of his marrow contained this genetic error.

A family friend with the same type of cancer told Eichner to call a doctor named Brian Druker right away. Dont do anything before you see him, the friend told Eichner a couple of days after his diagnosis. Three days later, Eichner got a call from Druker, whod mysteriouslyEichner didnt know exactly howgotten his phone number. During the next twenty minutes, Druker talked Eichner down from his panic, assuring him that, being in the early stages of the disease, Eichner could wait a week or two before making the trip south to Oregon Health and Science University (OHSU), where Druker had been treating and researching leukemia since 1993. He gave Eichner his professional blessing to go drink beer. It was August, and Eichner had been getting ready to leave for a day at Olympias annual summer Brew Fest, his brothers idea for getting his mind off leukemia for a while, when the phone rang.

Next page