Why Walls Wont Work

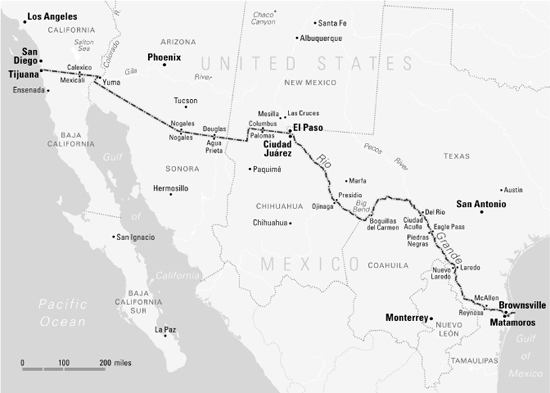

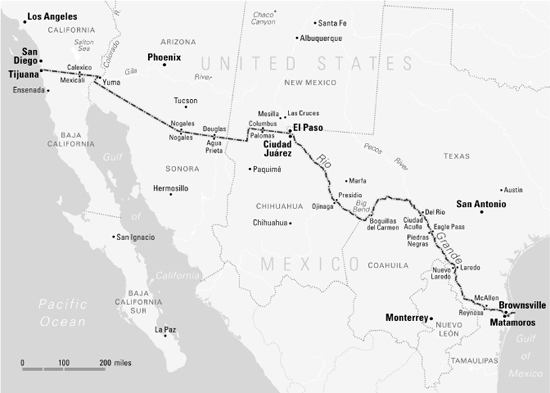

Locational Map of USMexico Borderlands

Artwork by Dreamline Cartography.

WHY WALLS WONT WORK

Repairing the USMexico Divide

MICHAEL DEAR

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford.

It furthers the Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship,

and education by publishing worldwide.

Oxford New York

Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi

Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi

New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto

With offices in

Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece

Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore

South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam

Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain

other countries.

Published in the United States of America by

Oxford University Press

198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016

Oxford University Press 2013

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a

retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior

permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law,

by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization.

Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the

Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form

and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

CIP record is available with the Library of Congress

ISBN 9780199897988

9 7 5 3 1 2 4 6 8

Printed in the United States of America

on acid-free paper

Contents

Frontispiece: Locational Map of USMexico Borderlands

John Russell Bartlett. Fording a Stream, Packmules Sink in Quicksand, 1849 (?)

USMexican Boundary Survey Map, 1853, Tijuana Section

Ancient Boundary Monument No. XVI

Monument No. 258, 1851

Monument No. 185, c. 1895

Major Cultural Traditions in Prehistoric US Southwest and Mexico

Georg Heinrich von Langsdorf Ein Tanz der Indianer in der Mision in St. Jos in Neu Californien / Dance of Indians at San Jose Mission, New California 1806

Plano de Matamoros y Brownsville / Plan of Matamoros and Brownsville 1890

Twin Cities of the US-Mexico border at the end of the Twentieth Century

The Comanche Empire and Its Alliance Network, 1830s1840s

Comanche Raiding Hinterland in Northern Mexico, 1820s1840s

Border Fencing During 1990s Operation Gatekeeper era

US-Mexico Border Ports of Entry, 2011

The Casa del Tnel, Tijuana, Baja California, 2007

A Manhole Cover in the City of Los Angeles, 2006

Miguel Cabrera, De mestizo y de india, coyote (From Meztizo and Indian, Coyote), 1763

Memin Pinguin Postage Stamps, Mexico 2005

Come Legally and Be Welcome

The Primary Fence at San Luis Colorado, Arizona, 2008

The Caged Fence outside Mexicali/Calexico, 2008

The Floating Fence at Algodones Dunes, California, 2008

Location of Private Detention Centers in the US, 2011

Memorial to Eight Women Found Murdered in Ciudad Jurez, 2004

Mexican Democratic Traditions, Ensenada, Baja California, 2006

Ancient Monument No. 1 at El Paso

Monument No. 122A

Monument No. 122A (detail)

Population growth, selected border cities, 19802005

Percentage of people with no confidence in four Mexican institutions, 2006

Percentage of people having a lot of trust in Mexican institutions, 2010

THE USMEXICO borderlands are among the most misunderstood places on earth. The communities along the line are far distant from the centers of political power in each nations capital. They are staunchly independent and composed of many cultures with hybrid loyalties. Historically, the eastern border counties were among the poorest regions in both countries; those in the center were sparsely populated agricultural and mining districts; and in the more affluent west, the upstart Baja California was always more closely connected to the State of California than to Mexico. Nowadays, border states are among the fastest-growing regions in both countries. They are places of teeming contradiction, extremes of wealth and poverty, and vibrant political and cultural change.

There are also enormous tensions along the borderlands, associated with undocumented immigration and drug wars. Neither of these problems originated in the borderlands. Instead, they came from outside, and borderland communities have limited capacity for self-determination in such matters. At the national level, the US and Mexico seek security and peace through the sacrifices of the small subset of their populations that resides in the border region. They are the people who must endure the exogenously-induced trials, often with scant assistance from their national and local governments beyond unpredictable military and police interventions. Border dwellers have made what adjustments they can, along the way demonstrating a remarkable durability and adaptability based in centuries of co-existence.

Mutual interdependence has always been the hallmark of cross-border lives. Over time, a series of binational twin cities sprang up along the line, with identities sufficiently distinct to warrant the collective title of a third nation, snugly slotted in the space between the two host countries. The third nation does not divide Mexico and the US but instead acts as a connective membrane uniting them. This way of looking at the border substitutes continuity and coexistence in place of concerns with sovereignty and difference. It is a view that runs directly counter to received wisdom in the US, which regards the border as the last line of national defense against unfettered immigration and runaway global terrorism.

The current fortifications along the border are without historical precedent, and threaten to suffocate the arteries supplying the third nations oxygen. Even after the 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo established the international boundary, the dividing line remained loosely marked, haphazardly maintained, and casually observed. But in the 1990s, responding to increased waves of undocumented crossings from Mexico, large fences sprouted on the border edges of cities such as Tijuana and Ciudad Jurez. Then, following the attacks of 9/11, the US unilaterally adopted an aggressive program of constructing fortifications along the entire line.

The new walls, fences, and checkpoints rudely interrupted the lives and livelihoods of third nation dwellers. On the US side, the border became a fortress containing an archipelago of law enforcement and justice agencies dedicated to apprehension, detention, prosecution and deportation of undocumented migrants, all bolstered by a new industry of corporate security interests. On the Mexican side, tranquility was usurped from a different sourcethe federal governments war against drug cartels. As the numbers of dead catapulted into the tens of thousands, cartel power was consolidated and Mexico seemingly drifted toward becoming a failed state, incapable of maintaining order or fulfilling its other obligations.