S INCE THE ATTACKS OF 9/11 , the United States has steadily ramped up security along the US-Mexico border, transforming Americas legendary Southwest into a frontier of fear. Veteran journalist Peter Eichstaedt roams this fabled region from Tucson, Arizona, to El Paso, Texas, bringing readers face-to-face with the victims, power players, and personalities that have riveted US attention on border security. By exploring the illicit paths of guns, money, drugs, and people as they flow back and forth across the US-Mexico border, Eichstaedt sheds light on the policies that contribute significantly to violence, abuse, and deathwhat most see as only Mexicos problems.

He shares the eye-opening stories of migrants, desperate for work or to be reunited with family, who risk arrest and deportation by attempting to cross multiple times; accompanies the border patrol on a nighttime ride as immigrants are caught, then follows them through the system as they are jailed and deported; talks to humanitarians who are technically breaking the law by transporting lost, dehydrated migrants; and spends time with a Mexican coffee-growing cooperative whose fair-pay ethos eliminates the need for its growers to look to the US for a decent wage.

Presenting humane alternatives to fear and steel fences and offering solutions to the immigration crisis, The Dangerous Divide explores Americas tortured relations with Mexico, ultimately focusing on hopeful measures and providing a rational and workable way out of the border and immigration problem.

ALSO BY PETER EICHSTAEDT

Above the Din of War: Afghans Speak About Their Lives, Their Country, and Their Futureand Why America Should Listen

Consuming the Congo: War and Conflict Minerals in the Worlds Deadliest Place

First Kill Your Family: Child Soldiers of Uganda and the Lords Resistance Army

If You Poison Us: Uranium and Native Americans

Pirate State: Somalias Terrorism at Sea

Copyright 2014 by Peter Eichstaedt

All rights reserved

Published by Lawrence Hill Books

An imprint of Chicago Review Press Incorporated

814 North Franklin Street

Chicago, Illinois 60610

ISBN 978-1-61374-836-7

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Eichstaedt, Peter H., 1947

The dangerous divide : peril and promise on the US-Mexico border / Peter Eichstaedt.

pages cm

Includes index.

ISBN 978-1-61374-836-7

1. Mexican-American Border Region. 2. Border securityMexican-American Border Region. 3. Illegal aliensUnited States. 4. CrimeMexican-American Border Region. 5. United StatesEmigration and immigrationGovernment policy. 6. MexicoEmigration and immigrationGovernment policy. I. Title.

JV6565.E43 2014

364.1370973dc23

2014002430

Interior design: Jonathan Hahn

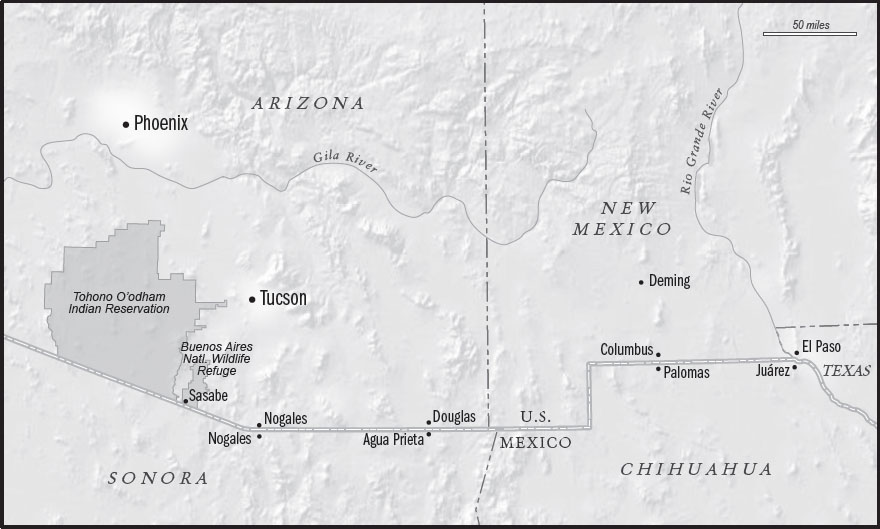

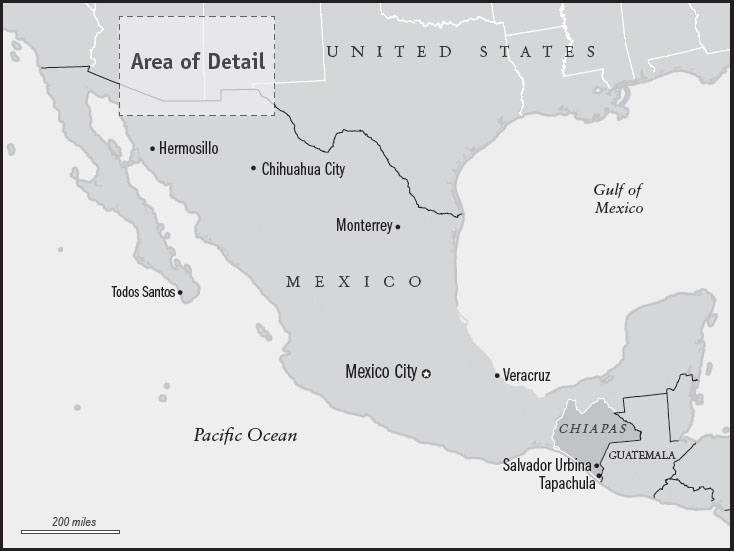

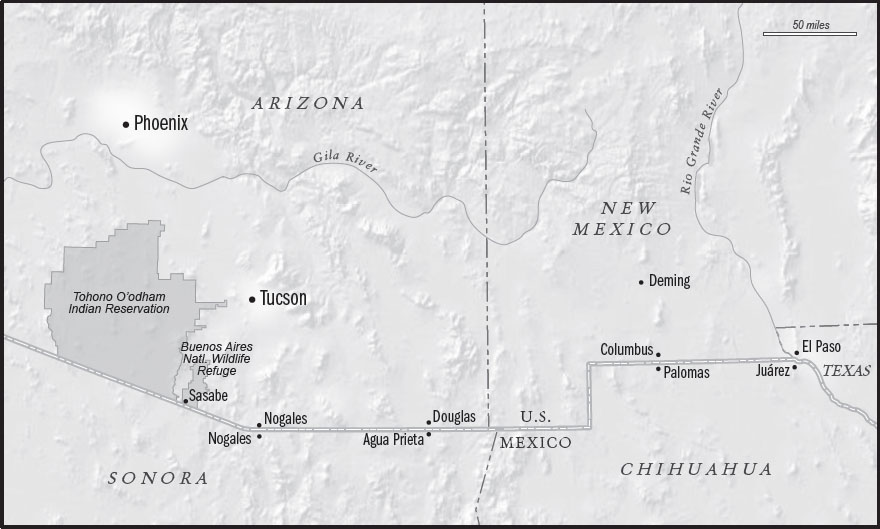

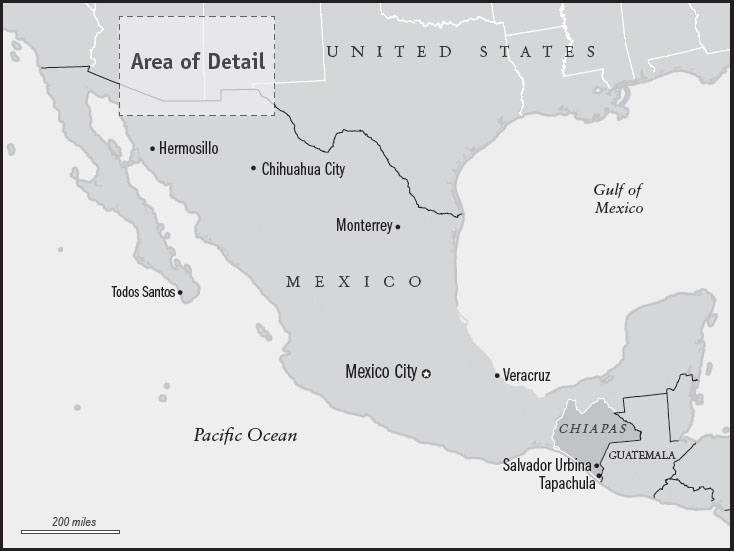

Map design: Chris Erichsen

Photos: Peter Eichstaedt

Printed in the United States of America

5 4 3 2 1

The mission bells told me, that I shouldnt stay.

South of the border, down Mexico way.

F ROM S OUTH OF THE B ORDER (D OWN M EXICO W AY )

Written by Kennedy/Carr

CONTENTS

Index

Prologue

A fter a flurry of packing, my suitcase was heaved into the belly of a Greyhound bus filled with students eager to say good-bye to the dreary dampness of the Columbus, Ohio, winter. It was early January 1967, just after the Christmas holiday break, and I was a sophomore at Ohio State University on my way to Mexico.

Months earlier my roommate had asked if I was interested in joining him in a program where OSU students spent a few months living and studying at the University of the Americas in Mexico City with full credit for classes. Great, I thought. It was something that I could easily fit into my studies, which at the time were aimless.

The war in Vietnam was heating up, and draft-eligible young men like me who were not in school were on their way to army boot camp. Antiwar protests were a regular occurrence and increasingly violent. The following year, 1968, America would convulse, perhaps changing forever. The Olympic Games in Mexico City would see black-gloved fists raised in protest against racism even as Alabama governor George Wallace campaigned to be president. Two American heroes, Robert F. Kennedy and Martin Luther King Jr., would die from assassins bullets. The Democratic and Republican Party conventions in Chicago and Miami, respectively, would devolve into clouds of tear gas and flailing nightsticks. It was a good time to get out of the country for a while. As the war in Vietnam dragged on, chances were good that Id be going sooner or later. When I asked my parents if I could go to Mexico, they readily agreed.

My prior contact with Mexico and Mexicans had been nonexistent. I had grown up in the farm belt of southern Michigan surrounded by fields of towering sweet corn, wide rows of luscious strawberries, and leafy orchards of trees laden with apples, peaches, and pears. The crops and fruit were picked by families of seasonal workers from Mexico, who for the most part kept to themselves. My notions of Mexico had been shaped by cartoon characters like Speedy Gonzales, comedian Jose Jimenez, and postcard caricatures of sandal-clad men with large sombreros sleeping against saguaro cacti.

At Laredo, Texas, we crossed into Mexico and I felt the thrill of finally entering foreign territory. After a lunch in a cavernous restaurant in Monterrey filled with plants, birds, and music, we rolled through the dark mountains, passing other buses on winding roads and around blind curves. The next morning, we arrived in Mexico City. Alive and well.

I roamed the city freely during those months and learned the pleasures of mole sauce and soft tacos filled with minced porka far cry from the fare found in Mexican restaurants across the American Southwest. I wandered the expanses of the Zcalo plaza in the heart of the city; drifted in the floating gardens of Xochimilco; climbed the stone Aztec pyramids of Teotihuacn; and marveled at the mariachi mecca of Plaza Garibaldi. I frequented the stunning Museum of Natural History, home to grand stone artifacts of the Toltecs and Aztecs, including the mystical Mayan calendar.

I returned home with a head full of Central and South American history and culture and a basic knowledge of Spanish. Mexico felt comfortable, if not familiar, and I would return.

In the mid-1970s, I settled in Santa Fe, New Mexico, drawn by its Southwestern lifestyle saturated with the culture and history of Mexico. Founded in about 1610 by Spanish explorers who rode north from Mexico City, Santa Fe is a blend of the Native American cultures of the ageless pueblos along the Rio Grande, the centuries of Spanish and Mexican rule, and the coming of the Anglo-Americans.

I worked for the New Mexican newspaper, established in 1849, making it the oldest daily newspaper west of the Mississippi River. I rummaged the musty archives from when the newspaper was printed in Spanish and English with stories of outlaws, shootouts, and cattle rustlers. An entire issue was dedicated to the infamous 1916 raid by Mexican revolutionary Pancho Villa on Columbus, New Mexico, a dusty town on the Mexico border.

Next page