The Death of Josseline

Immigration Stories from the Arizona Borderlands

Margaret Regan

Beacon Press

Boston

For my parents

Mary G. Regan,

great-granddaughter

of Irish famine refugees

&

William L. Regan,

grandson of Irish immigrants

who died young, poor,

and far from home

Authors Note

The terms used to refer to border crossers run the gamut, from the Border Patrols bodies and UDAs (undocumented aliens) to the reverential pilgrims of Tucson writer Demetria Martinez. In between are illegal aliens and entrants. In this book, I have chosen to use the neutral term migrants.

I reconstructed Josselines journey from multiple interviews, from the data in the Pima County medical examiners autopsy report, and from my own hike into Cedar Canyon, where she died.

Contents

(Revised for the paperback edition)

Prologue. The Death of Josseline

She was just a little girl. She was on her way to her mother.

Kat Rodriguez, human rights activist

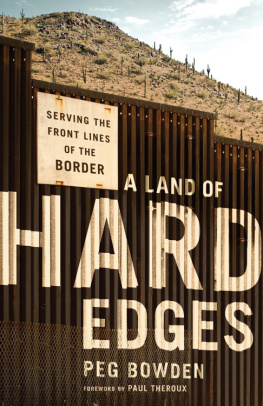

Josseline shivered as she stepped over the stones and ducked under the mesquites. She was in Arizona, land of heat and sun, but on this late-January day in 2008, it was cold and damp. The temperature was in the 50s, and the night before it had dropped to near freezing. A winter rain had fallen, and now the desert path was slippery and wet, even more treacherous than it had been before.

Josseline was seven miles north of the Mexican border, near the old ranching town of Arivaca, in prime Sonoran Desert. It was a wonderland of cactus and mesquite, beautiful but dangerous, with trails threading through isolated canyons and up and down hills studded with rocks. She had to get through this perilous place to get to her mother. A little girl with a big nameJosseline Jamileth Hernndez Quinterosshe was five feet tall and a hundred pounds. At fourteen, young as she was, she had an important responsibility: it was her job to bring her little brother, age ten, safely to their mother in Los Angeles. The Hernndez kids had never been away from home before, and already theyd been traveling for weeks. Now they were almost there, just days away from their mothers embrace.

The family hadnt been together in a long time. Their father, Santos, was living somewhere in Maryland; their mother, Sonia, in California. Both parents were undocumented, working in the shadows. Back home in El Salvador, the kids lived with relatives, and in the years their mom was gone, Josseline had become a little mother to her brother. Finally, Sonia had worked long enough and hard enough to save up the money to send for the children. Shed arranged for Josseline and her brother to come north with adults they knew from home, people she trusted.

The group had crossed from El Salvador into Guatemala, then traveled two thousand miles from the southern tip of Mexico to the north. The trip had been arduous. Theyd skimped on food, slept in buses or, when they were lucky, in casas de huspedes, the cheap flophouses that cater to poor travelers. In Mexico, the migrants feared the federales, the national police, and now, in the United States, they were trying to evade the Border Patrol, the dreaded migra.

But here in the borderlands they were in the hands of a professional. Like the thousands of other undocumented migrants pouring into Arizonajumping over walls, trekking across mountains, hiking through desertstheir group had contracted with a coyote , a smuggler paid to spirit them over the international line. The coyotes fee, many thousands of dollars, was to pay for Josseline and her brother to be taken from El Salvador all the way to their mother in Los Angeles. So far, everything had gone according to plan. They had slipped over the border from Mexico, near Sasabe, twenty miles from here, and had spent a couple of days picking their way through this strange desert, where spiky cacti clawed at the skin and the rocky trail blistered the feet. The coyote insisted on a fast pace. They still had a hike of twenty miles ahead of them, out to the northbound highway, Interstate 19, where their ride would meet them and take them deep into the United States.

Josseline (pronounced YO-suh-leen) pulled her two jackets closer in the cold. She was wearing everything she had brought with her from home. Underneath the jackets, she had on a tank top, better suited to Arizonas searing summers than its chilly winters, and shed pulled a pair of sweatpants over her jeans. Her clothes betrayed her girly tastes. One jacket was lined in pink. Her sneakers were a wild bright green, a totally cool pair of shoes that were turning out to be not even close to adequate for the difficult path she was walking. A little white beaded bracelet circled her wrist. Best of all were her sweats, a pair of butt pants with the word hollywood emblazoned on the rear. Josseline planned to have them on when she arrived in the land of movie stars.

She tried to pay attention to the twists and turns in the footpath, to obey the guide, to keep up with the group. But by the time they got to Cedar Canyon, she was lagging. She was beginning to feel sick. Shed been on the road for weeks and out in the open for days, sleeping on the damp ground. Maybe shed skimped on drinking water, giving what she had to her little brother. Maybe shed swallowed some of the slimy green water that pools in the cow ponds dotting this ranch country. Whatever the reason, Josseline started vomiting. She crouched down and emptied her belly, retching again and again, then lay back on the ground. Resting didnt help. She was too weak to stand up, let alone hike this roller-coaster trail out to the road.

It was a problem. The group was on a strict schedule. They had that ride to catch, and the longer they lingered here the more likely theyd be caught. The coyote had a decision to make, and this is the one he made: he would leave the young girl behind, alone in the desert. He told her not to worry. They were in a remote canyon that was little traveled, but the Border Patrol would soon find her. Nearby, he claimed, were some pistas, platforms that la migra used as landing pads for their helicopters. Surely theyd be by soon, and they would take care of her. Her little brother cried and begged to stay with her. But Josseline was his big sister, and Josseline insisted that he go. As he recounted later, she told him, T tienes que seguir a donde est Mam. You have to keep going and get to Mom.

The other travelers grabbed the wailing boy and walked on, leaving his sister alone in the cold and dark. She had only her clothes to keep her warm. On her first night alone, the temperature dropped below freezing, to 29 degrees. By the weekend, when her brother arrived safely in Los Angeles and sounded the alarm, Arivaca had warmed upto 37 degrees.

Three weeks later, Dan Millis was getting ready to go out on desert patrol. He was filling up a big plastic box with nonperishables for migrantsgranola bars, applesauce, Gatoradeand new socks, something the weary walkers always seemed to need. He tossed the box into his car and then loaded up dozens of gallons of water. A former high school teacher, Dan, twenty-eight, was an outdoors enthusiast who was spending a year volunteering with No More Deaths, a Tucson group determined to stop the deaths of migrants in the Arizona deserts. As the United States clamped down on the urban crossings, desperate travelers were pushing into ever more remote wilderness and dying out there in record numbers. So the No More Deaths folks began hiking the backcountry in the Arivaca borderlands, an hour and a half southwest of Tucson, setting out water and food in the rugged hills. Sometimes theyd meet up with migrants who were lost or sick, and they would provide first aid. But sometimes they found a body.