KEN ELLINGWOOD

HARD LINE

Ken Ellingwood is a staff writer for the Los Angeles Times, for which he covered the U.S.-Mexico border from 1998 to 2002. He has also reported from Atlanta, and his journalism has won several awards. Ellingwood is currently based in the newspapers bureau in Jerusalem, where he lives with his wife and daughter.

FIRST VINTAGE BOOKS EDITION, JULY 2005

Copyright 2004 by Ken Ellingwood

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Vintage Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto. Originally published in hardcover by Pantheon Books, a division of Random House, Inc.,

New York, in 2004.

Vintage and colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

The Library of Congress has cataloged the Pantheon edition as follows:

Ellingwood, Ken.

Hard line: life and death on the U.S.-Mexico border / Ken Ellingwood.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references

1. Alien labor, MexicanMexican-American Border Region.

2. Illegal aliensMexican-American Border Region. I. Title.

HD8081. M6E4 2004

972.1084dc22

2003064694

eISBN: 978-0-307-53036-3

Author photograph Iris Schneider

www.vintagebooks.com

v3.1

For my grandmother,

Mara del Socorro Snchez,

with gratitude

Contents

Acclaim for Ken Ellingwoods

HARD LINE

ASan Francisco ChronicleBook of the Year

Vivid, humane, and often moving. This is a major storyall the more so because most of the public doesnt know about itand Mr. Ellingwood tells it crisply and clearly.

The New York Sun

Ellingwood is absolutely the right person to describe this complex situation for which there are no answers. Readers will be rapt.

MSNBC.com

A gritty look at the politics, culture and harsh realities that exist along one of the most controversial borders in North America.

Tucson Citizen

Terrific reporting. An important narrative.

The Post and Courier (Charleston)

What makes Ellingwoods portrayal so remarkable is his ability to examine the border from nearly every conceivable angle. Ellingwood transcends ideologies, rendering the border and all who dwell along it with the utmost respect and care.

Publishers Weekly (starred)

A tapestry of dilemma and injustice and anger, written so well as to make anyone see clearly the dangerous terrain and loyalties and lives of the border. This book is powerful and vital and absolutely necessary.

Susan Straight, author of Highwire Moon

Note on Accents

Because Americans, whatever their origin, tend to spell their names without accents, I have applied that style to the names of Mexican-Americans in this book; the names of Mexicans are spelled with the accents.

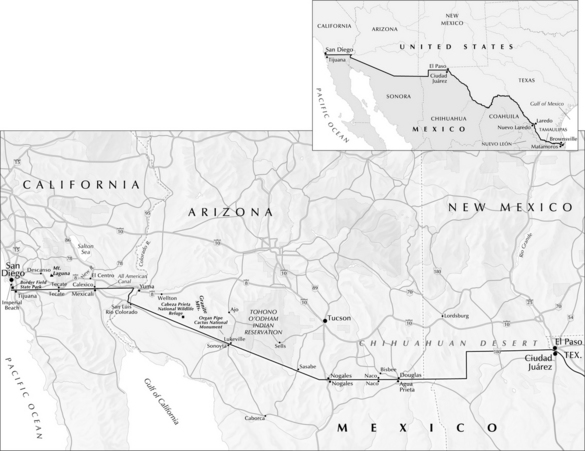

THE U.S.-MEXICO BORDER

PROLOGUE

The funeral is quick and dirty. The man is buried on a sunny California morning in much the same way he was foundalone and nameless and, from what anyone can tell, very far from home. His border-crossing journey ends in a pressed-wood box with screw-on plastic handles and a coroners case number scrawled on the lid. Two of us look on as a trio of gravediggers with dour expressions and a pleasant fellow from a local funeral home lower the coffin into the slick Imperial County clay. They repeat the procedure with the boxed remains of a woman whose name also remains a mystery. With the addition of these two bodies, 133 undocumented immigrants now lie in this paupers graveyard, their resting places designated by plain concrete loaves labeled John Doe or Jane Doe.

The burial in this muddy graveyard in the town of Holtville represents the final step in this immigrants ill-starred trip to the north. His remains were found three months earlier, in a creosote-specked wash deep in the California desert. During the peak of blistering summer temperatures, a deputy county coroner named Gary Hayes had to navigate his pickup miles into the parched countryside to reach the body. By the look of things, the migrant had succumbed first to the scorching heat and then, after death, to the messy work of scavenging animals. Coyotes, probably. As Hayes went about gathering the remains, the two men who had found the body, a pair of civilian contract workers who had been tending warning signs around the surrounding military bombing range, stood a healthy distance away from the tangle of clothes and skeletal remains and chatted with the handful of military officers and Border Patrol agents who had shown up. As Hayes searched the surroundingsone of the dead mans boots was missingRichard Duarte, one of the sign tenders, squinted out over the seemingly endless desolation and contemplated the futility of the migrants journey through this awful terrain. These guys dont know whats happening out here, he mused. The deserts a dangerous area. People just want to get across. Theyll listen to whatever people say.

Indeed, the U.S.-Mexico border is a dangerous place, and always has been. Its home to criminal operators of every stripesmugglers, drug lords, fugitives and crooked copsand to some of the most unforgiving natural surroundings in either country. In years past, illegal border crossers had fallen prey to rapists and hardened killers, rain-engorged rivers, freeway traffic and their own ignorance and poor judgment. But by 2001, the number of fatalities across the nearly two-thousand-mile international boundary was hitting levels that dismayed even veteran border observers. More than three hundred were dying annually en routeenough to fill a passenger jetliner, as some pointed out. The difference now was that it was the borders brutal physical surroundingsnot bandits or gunmenthat were doing the killing.

While past border media coverage had focused heavily on drug trafficking and the battle against runaway illegal immigration, this new death toll among undocumented migrants sneaking north into California and Arizona suddenly became a dominant theme at the border, as well as a disturbing problem for U.S. and Mexican officials far away in their nations capitals. The safety issue grew more urgent with each new group of migrants that found itself in peril here in the deep desert sands of Imperial County, in the snow-topped mountains outside of San Diego and in the blast-furnace summertime heat of Arizona.

The reason for the deadly shift was man-made. A few years earlier, for the first time in its history, the U.S. government had made a sweeping effort to stave off illegal crossings in heavily populated areas that were well-known trouble spotsmost prominently San Diego, California, and El Paso, Texas. These zones had once been virtual pedestrian high-ways for job-hungry immigrants lacking papers, but the huge buildup of Border Patrol agents in these places during the 1990s crackdown sent smugglers on an end run. They were soon leading their charges into the bleak and sparsely settled hinterlandsover mountains, across rivers and through merciless stretches of desert. Capture by the Border Patrol was less likely in these areas, but the risk of perishing rose dramatically.