PREFACE

In February 2006 I was traveling in a crowded van snaking its way along a dusty, potholed dirt road in the state of Guerrero, Mexico. The van serves as a small bus that takes people back and forth between the city of Iguala and one of the smaller towns whose inhabitants do their shopping and run errands there. I sat between two men and a woman sharing a narrow bench. Everyone spoke Nahuatl, the language used in that part of Guerrero. I struck up a conversation with the young man sitting on my left and found out that his parents had taken him and several of their other children with them to Houston, Texas, several years earlier. He switched to Spanish, then English, telling me he had recently come back from northern Mexico to make sure that his mother made it safely back across the border after a short visit to their hometown. The son planned to stay a bit longer before returning to the United States. This young man also told me the person who had most helped him learn English was a retired teacher in Houston, and he asked me for my e-mail address to give to her. It turns out that the teacher, who writes juvenile fiction, was interested in the native people of Mexico, a topic on which I have considerable expertise. I corresponded with her and a year later stayed at her house during my first trip to the United States to start doing research on undocumented workers. My experience in that van is typical of the work done by anthropologists whose investigations sometimes lead us in unexpected directions.

In todays increasingly interconnected world, it does not make much sense to study migration by looking only at people in their place of origin, or conversely, their place of destination. By simultaneously doing fieldwork in the United States and in Mexico, I discovered that I could sometimes find out more about a town in Mexico from an interview with someone living in an apartment in a large urban center in the United States; likewise, I learned as much about the immigration experience from interviewing former migrants now living in Mexico as I did from talking to migrants in their homes and places of work north of the border. Talking to people on both sides of the U.S.-Mexico border enabled me to identify the hopes and dreams, as well as the disappointments and anxieties, of both undocumented workers and those they left behind.

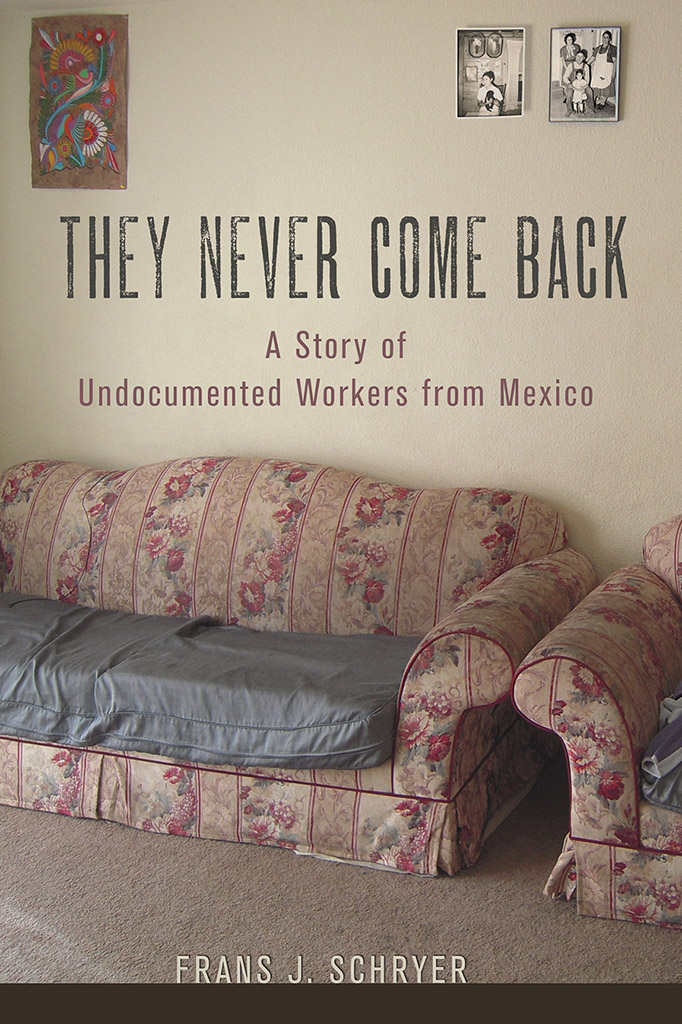

In writing about undocumented workers, I want to give readers a good sense of what life is like for those who make it across the border. My goal is to provide American citizens, including those of Mexican descent, with a better understanding of undocumented migrants and the contribution undocumented workers make to the American economy. My hope is to illuminate not only the situation of undocumented migrants but also the urgent need to change the current system of immigration that is just not working. The focal point of this book is the sending communities. The existing literature usually provides more information on Mexican immigrants working and living in the United States than on the hometowns of those immigrants. My study will do the opposite. Previous research in Mexico and my knowledge of Nahuatl enables me to provide new insights into the impact of migration on sending communities and the emergence of new attitudes among those left behind. At the same time I provide ample coverage of the experiences and feelings of undocumented workers.

Until now, I have written books and journal articles for specialists in the field, presenting complex ideas using abstract, technical language. In contrast, this book is an example of public anthropology, which presents research results to a broader audience with the intention of contributing to public discussions on policy. I believe that the research of scholars and the implications of that research can beand should beexplained in a way that is both thought-provoking and understandable to those without advanced academic degrees.

INTRODUCTION

Millions of undocumented Mexicans living in the United States feel boxed in. They might want to attend weddings in their hometowns or spend time with dying grandparents; but they need to keep their jobs and face increasing risks if they leave and then reenter. Consequently, few go back and forth anymore. These workers face additional challenges since it is now almost impossible for them to obtain a work permit or even identity documents. Consequently, to obtain work they have to acquire false documents or use the names of friends or relatives with valid Social Security numbers or work permits. Many cannot get or renew a drivers license yet they need to drive as part of their job or to find work. So they drive without a license. They do not like living this lie, but what other choices do they have?

The influx of undocumented workers is a consequence of the economic integration of the United States, Canada, and Mexico. The same McDonalds restaurants and other fast-food chains are found in each county. The major car makers have assembly plants all over the continent. Several large Mexican firms now do as much business in some parts of the United States as they do at home. Nowadays you are as likely to find an Avon lady or someone selling Amway products in a small town in southern Mexico as in Toronto or in downtown Los Angeles. You will see the same kind of iPods or cell phones wherever you go. The greater ease of circulation of goods and capital, especially after the implementation of the 1994 North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), alongside further restriction on the movement of workers across borders, is a contradiction. An increase of undocumented workers, notwithstanding an agreement to reduce the need for Mexicans to find work in the United States, is another contradiction. Before the turn of the century Mexican men made frequent trips back home to visit their families, and mothers raised their children in Mexico. Today women are joining their husbands in the United States and young couples are migrating together, resulting in an increase in children born in the United States. Such children automatically become American citizens yet any brothers or sisters born in Mexico are aliens. Such alien offspring are Mexican citizens who will not learn about Mexican history; likewise children born in the U.S., but whose parents were forced to return to Mexico when they were still young, will grow up not knowing English or American history. All these contradictions are the outcome of a dysfunctional and hypocritical immigration policy.

Imagine if you found out that you are a Mexican when you thought you were an American. Imagine if you had no other choice but to move to a neighboring country as the only way to make a decent living, and then you are cut off from your family even though the place where they live is not that far away. Imagine if you had to make the choice between going back home to attend your fathers funeral or keeping the job you need to support your children. Imagine going to a bus terminal after being away from your hometown for twenty years and realizing only after two hours that the stranger pacing back and forth is actually your father who is supposed to meet you and bring you and your baby back to the place you were born.

This book tells the stories of undocumented migrant workers, as well as the people they leave behind, using as an example people from the Alto Balsas region in the Mexican state of Guerrero. This part of Mexico is a good example to use because the proportion of migrants to the United States who are undocumented is very high, possibly over 90 percent. These migrant workers experience the inconsistencies of U.S. immigration policy; their stories illustrate how the economic integration of the North American continent, which at the same time restricts the movement of labor, is mirrored in peoples lives. Migrants from this part of Mexico started working en masse as undocumented laborers only about fifteen years ago. Hence their experiences better illustrate these contradictions than the stories of those who emigrated before 1990. The workers described in this book are also representative of a recent trend in migration from the southern half of Mexico, where many people speak an indigenous language as their mother tongue.