Contents

Guide

Simon & Schuster

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10020

www.SimonandSchuster.com

Copyright 2020 by Jerry Mitchell

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form whatsoever. For information address Simon & Schuster Subsidiary Rights Department, 1230 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10020.

First Simon & Schuster hardcover edition February 2020

SIMON & SCHUSTER and colophon are registered trademarks of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases, please contact Simon & Schuster Special Sales at 1-866-506-1949 or .

The Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau can bring authors to your live event. For more information or to book an event contact the Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau at 1-866-248-3049 or visit our website at www.simonspeakers.com.

Interior design by Ruth Lee-Mui

Jacket design by Jackie Seow

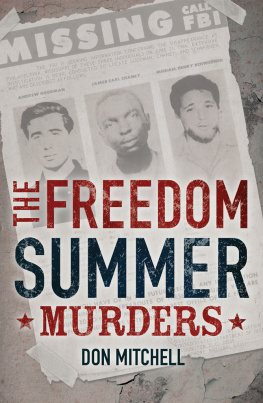

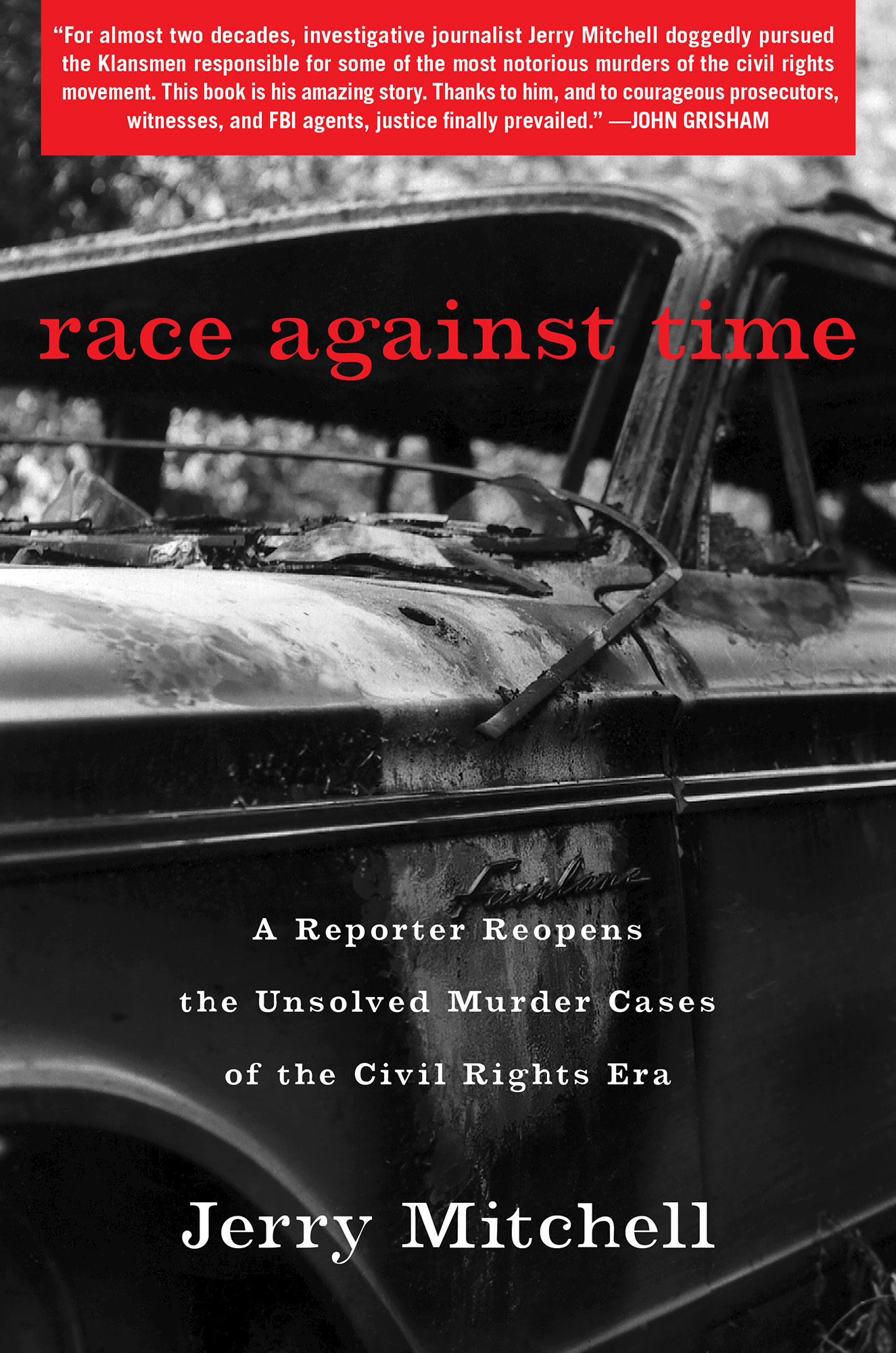

Jacket Photograph, from the FBI Archives, Depicts the Burned Out Station Wagon Of Slain Civil Rights Workers

James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner as it was Dredged from the Bogue Chit to Swamp on June 23, 1964.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available.

ISBN 978-1-4516-4513-2

ISBN 978-1-4516-4515-6 (ebook)

To the One who loves justice

PART I JAMES CHANEY ANDREW GOODMAN MICHAEL SCHWERNER

1

The Ford station wagon topped a hill before disappearing into the darkness. Mickey Schwerner drove, deep in thought. Fellow New Yorker Andy Goodman propped his body against the passenger door, drifting off to sleep. Mississippi native James Chaney, the lone African-American, swallowed hard, shifting in the backseat.

Two cars and a pickup truck raced to catch up. Schwerner spotted them in his rearview mirror. Uh-oh.

The noise woke Goodman. What is it? What do they want?

Schwerner rolled down the window and stuck out his arm, motioning for the car to pass. Is it a cop?

Goodman gazed back. I cant see.

The car crunched into the wagon, and Schwerner wondered aloud if their pursuers were playing a joke.

They aint playin, Chaney said. You better believe it.

Metal and glass smashed again. What are we going to do? Goodman asked.

Schwerner told his fellow civil rights workers to hold on. He jerked the wagon off the blacktop onto a dirt road, sending up a swirl of dust. His pursuers werent shaken. Instead, they flipped on police lights and began to close the distance again.

Schwerner spotted the crimson glow in his rearview mirror and cursed. It is a cop.

Goodman advised, Better stop.

Okay, sit tight, you guys. Dont say anything. Let me talk.

Schwerner turned to Chaney. Well be all right. Just relax.

The wagon squeaked to a stop. Doors opened and slammed shut, interrupting a chorus of frogs.

Flashlights bathed them in light. A Klansman with a crew cut told Schwerner, Yall think you can drive any speed you want around here?

You had us scared to death, man, Schwerner replied.

Dont you call me man, Jew-boy.

No, sir, what should I call you?

Dont call me nothing, nigger-lovin Jew-boy. You just listen.

Yes, sir.

The crew cut moved closer to the driver and sniffed. Hell, youre even startin to smell like a nigger, Jew-boy.

Schwerner reassured Goodman, Well be all right.

Sure you will, nigger lover.

He seen your face, a fellow Klansman advised. That aint good. You dont want him seein your face.

Oh, the crew cut replied, it dont make no difference no more.

He pressed his pistol against Schwerners temple and pulled the trigger. Blood spattered against Goodman. Oh, shit, were into it now, boys, one Klansman said.

Three shots echoed in the night air.

You only left me a nigger, but at least I shot me a nigger, another Klansman said with a chuckle, joining a choir of laughter.

Everything went dark. White letters spelled out on a black screen: Mississippi, 1964.

I was one of several dozen people watching the film Mississippi Burning tonight, squeezed inside a theater where coarse blue fabric covered metal chairs. Nothing distinguished this movie house from thousands of other multiplexes across America. Except, of course, that this was not just any place.

This was Mississippia place where some of the nations poorest people live on some of the worlds richest soil, a place with the nations highest illiteracy rate and some of the worlds greatest writers. Decades earlier, Mississippi had bragged in tourist brochures about being The Hospitality State. What it failed to mention was it led the nation in the lynchings of African-Americans between the Civil War and the civil rights movement.

Through newspaper photographs and television news, Americans had witnessed the brutality in Mississippi for themselves. In spring 1963, they saw police dogs attack civil rights workers in Greenwood. Months later, they observed the trail of blood left by NAACP leader Medgar Evers when he was assassinated in the driveway of his Jackson home. During the summer of 1964, Americans watched sailors tromp through swamps in search of the three missing civil rights workers, Chaney, Goodman, and Schwerner, who were last seen leaving the small town of Philadelphia, Mississippi.

For forty-four days, the drama unfolded before the nation. Mississippis US senator Jim Eastland told President Lyndon B. Johnson that he believed the missing trio were part of a publicity stunt, and Mississippi governor Paul Johnson Jr. suggested they could be in Cuba. Days before the FBI unearthed their bodies on August 4, 1964, the governor spoke at the Neshoba County Fair, just two miles from that grisly discovery. He told the cheering crowd there were hundreds of people missing in Harlem, and somebody ought to find them.

The killings came to define what the world thought of Mississippi, and no subsequent events had dislodged it by the time I came here in 1986 as the lowliest of reporters for the Pulitzer Prizewinning newspaper The Clarion-Ledger. I arrived the day before my twenty-seventh birthday, the same day the paper carried a story about the burial of Senator Eastland, the longtime chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee who had bragged about having extra pockets sewn into his jacket to kill all those civil rights bills.

The days of Jim Crow had long passed when I drove into this capital city of nearly 200,000 with my wife and our baby daughter. Jackson was bursting with New South pride and Old South prejudice, but doing its best to conceal the latter. I had been here three years now, from 1986 to 1989, and put thousands of miles on my Honda hatchback in that time, trying to find my feet as a reporter while trying to understand this beautiful and haunted state. When I first heard Mississippians refer to the War, I thought they were talking about Vietnamonly to discover they meant their great-grandfathers Civil War, which their descendants, it seemed, had never stopped fighting.

At my desk, I had read the January 9, 1989, issue of Time magazine, which featured the Mississippi Burning movie on the cover. Jackson had been abuzz about the film since last spring, when some residents complained about Hollywood liberals invading their town. Disdain turned to curiosity when word spread that actor Gene Hackman had been spotted at Hal and Mals, a popular pub and eatery. Lunch crowds doubled.