Be ashamed to die until you have won some victory for humanity.

Horace Mann, Antioch College commencement address, Yellow Springs, Ohio, 1859

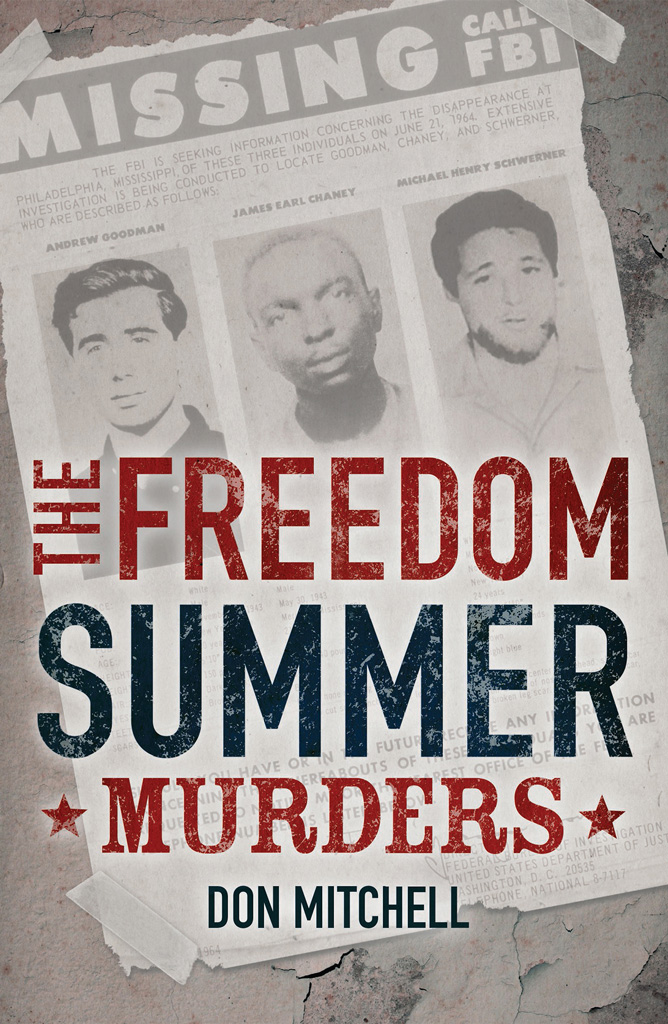

In June 1964, Willie Peacock, a member of the civil rights organization the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), was arrested, along with several black colleagues, on a trumped-up traffic charge outside Columbus, Mississippi. He was describing his treatment from the police officers in the county jail to a group of civil rights volunteers:

Nigger, do you believe Id just as soon kill you as look at you?

Yes, Willie responded to the police officer. But he wasnt fast enough. Whack! Willie was struck with the officers left hand.

Willie looked out at the sea of mostly white college students who had come to this safe, idyllic school nestled in the rolling farmlands of southwestern Ohio. He was giving them a firsthand account of what life was like in the South. And he unnerved his audience when Willies colleague occasionally rubbed his aching jaw where his teeth were still loose from the beating he took in that Mississippi jail just a few weeks before. Willie and his friends were speaking to the Freedom Summer volunteers who were training here in Oxford in preparation to live in Mississippi for the summer and register blacks to vote.

Willie Peacock (front row, third from left) attended a rally on the steps of the Hinds County Courthouse in Jackson, Mississippi, in October 1963.

Willie warned his idealistic young listeners: When you go down those cold stairs at the police station, you dont know if youre going to come back or not. You dont know if you can take those licks without fighting back, because you might decide to fight back. It all depends on how you want to die.

To be born black and to live in Mississippi was to say that your life wasnt worth much.

Myrlie Evers, wife of slain civil rights leader Medgar Evers

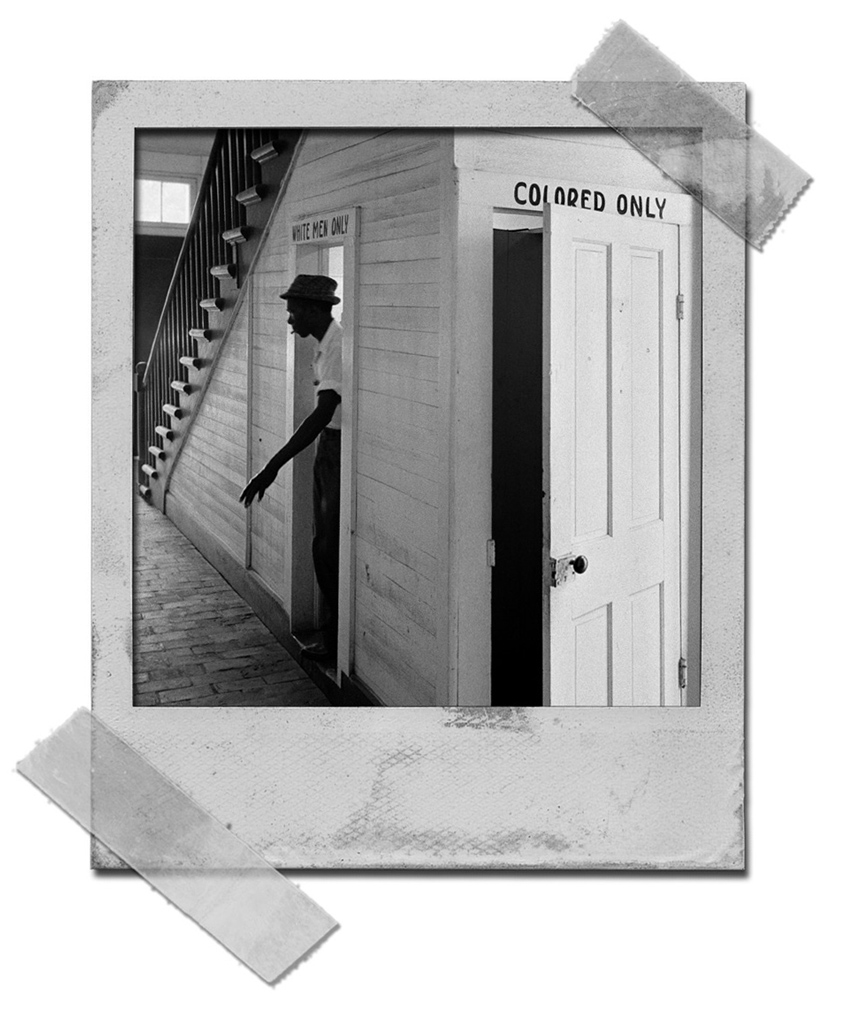

Blacks in the South were second-class citizens at best. Mississippi, like other southern states, operated under a policy of segregation, which meant keeping the white and black races separate. Blacks had different and usually inferior restaurants, restrooms, drinking fountains, waiting rooms, schools, hospitals, and housing. It was understood that blacks must be deferential to whites in virtually every interaction. If you were black and walking on the public sidewalk and white people approached, you had to step down into the street and let the white people use the sidewalk. And public transportation? If you were black, your place was at the back of the bus. And if the bus was crowded and a white passenger needed a seat, you better stand and give up that seat or it could mean jail, or a beating.

In its 1896 ruling in Plessy v. Ferguson, the US Supreme Court validated racial segregation in Mississippi and elsewhere when it ruled that states could require separate facilities (e.g., transportation, schools, restaurants) for blacks and whites as long as they were equal the so-called separate but equal doctrine. But in reality, while facilities for the races were frequently separate, they were seldom equal. The 1954 ruling in the case of Brown v. Board of Education overturned separate but equal. Segregation in public schools was prohibited and states were required to integrate immediately.

Segregated public facilities were a fact of life throughout the South.

But white officials in Mississippi dug in and refused to desegregate their schools. The white supremacists were determined to detect and destroy any effort to end segregation.

A July 1954 meeting of concerned whites in Indianola, Mississippi, led to the creation of the first Citizens Council. By October 1954, the council claimed to have more than twenty-five thousand members. The council was dedicated to preserving Mississippis social order of white dominance and the organized resistance to any federal government efforts in support of integration. Its membership was comprised of white citizens, many of whom were businessmen who believed that segregation could be preserved through legal, nonviolent means. The council simply relied on the use of threats, coercion, and economic retaliation against those who sought to change the status quo.

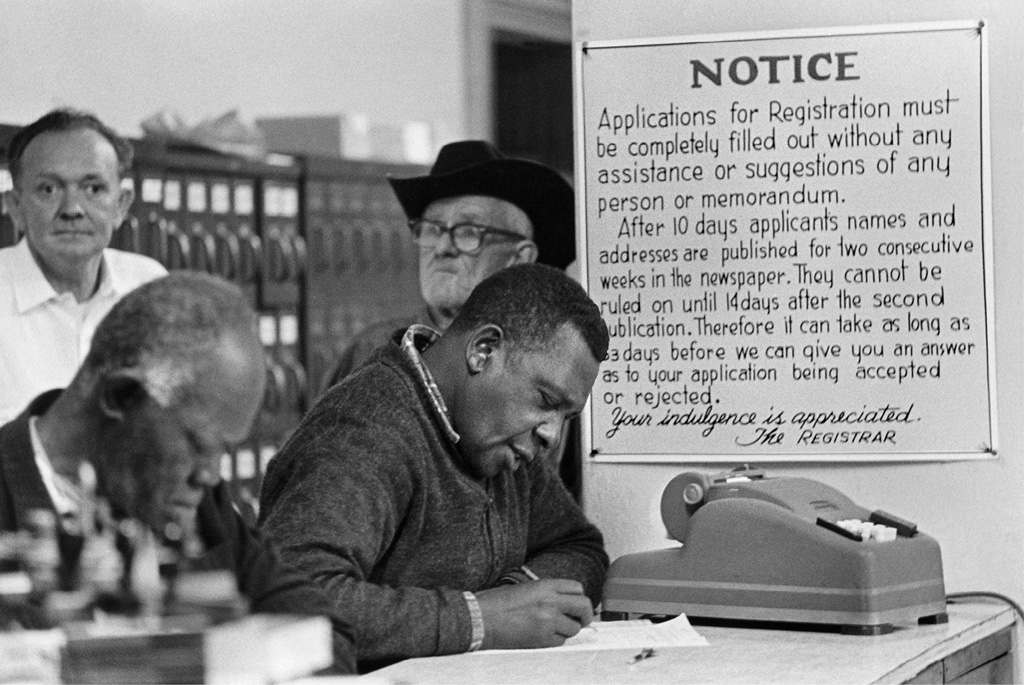

The most effective way for Mississippis white elites to deprive blacks of their voice in government was to deny them the right to vote. Individuals who tried to register blacks to vote, or encourage others to do so, could find themselves out of a job and labeled as virtually unemployable. Local banks could refuse to extend them credit, loans, or home mortgages. The council would take out advertisements in newspapers and list the names and addresses of individuals who were, or were suspected of being, civil rights activists. The white community would react quickly to these postings. Insurance policies could be canceled. Boycotts were arranged against merchants who were sympathetic to the civil rights movement.

In January 1964, at a courthouse in Mississippi, black applicants attempt to register to vote. The wall sign warns of the public exposure applicants will experience in order to intimidate black citizens.

The government of Mississippi felt so strongly about the need to protect segregation, it created its own spy agency to deal with the threat of integration. By an act of the Mississippi legislature, the Mississippi State Sovereignty Commission was created on March 29, 1956. The new organization was granted extensive investigatory powers. Anyone, black or white, who expressed support for integration, was involved in civil rights, or even had suspect political affiliations was a fitting target for commission investigators. The Sovereignty Commission exercised far-reaching authority on the people of Mississippi. It banned books, censored films, and closely examined school curriculums. It even censored national radio broadcasts and television programs.