A TRIANGLE SQUARE BOOK FOR YOUNG READERS

PUBLISHED BY SEVEN STORIES PRESS

Copyright 2020 by Bruce Watson and Rebecca Stefoff For permissions information see page 429.

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced,

stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any

form or by any means, including mechanical, electronic,

photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the

prior written permission of the publisher.

SEVEN STORIES PRESS

140 Watts Street

New York, NY 10013

www.sevenstories.com

School teachers may order free examination copies of Seven Stories Press titles. To order, visit www.sevenstories.com or send a fax on school letterhead to (212) 226-1411.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

NAMES: Watson, Bruce, 1953 author. | Stefoff, Rebecca, 1951 adaptor.

| Watson, Bruce, 1953 Freedom Summer.

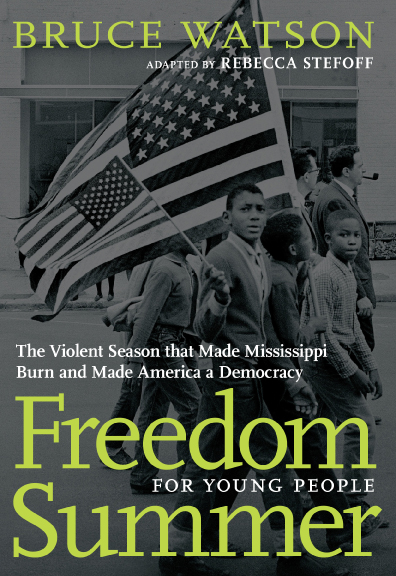

TITLE: Freedom Summer for young people : the violent season that made

Mississippi burn and made America a democracy /

Bruce Watson ; adapted by Rebecca Stefoff.

OTHER TITLES: Savage season of 1964 that made

Mississippi burn and made America a democracy

DESCRIPTION: New York : Seven Stories Press, [2020] | A Triangle

Square book for young readers. | Audience: Grades 79

IDENTIFIERS: LCCN 2020032394 (print) | LCCN 2020032395 (ebook)

ISBN 9781644210093 (hardcover) | ISBN 9781644210109 (trade paperback)

ISBN 9781644210116 (epub)

SUBJECTS: LCSH: African AmericansCivil rightsMississippiHistory20th

centuryJuvenile literature. | African AmericansSuffrageMississippiHistory

20th centuryJuvenile literature. | Mississippi Freedom ProjectJuvenile literature.

Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (U.S.)Juvenile literature.

Civil rights movementsMississippiHistory20th centuryJuvenile literature.

Civil rights workersMississippiHistory20th century

Juvenile literature. MississippiRace relationsHistory

20th centuryJuvenile literature.

CLASSIFICATION: LCC E185.93.M6 W28 2020 (print) |

LCC E185.93.M6 (ebook) | DDC 323.1196/0730904dc23

LC RECORD AVAILABLE AT HTTPS://lccn.loc.gov/2020032394

LC EBOOK RECORD AVAILABLE AT HTTPS://lccn.loc.gov/2020032395

BOOK DESIGN AND PHOTO RESEARCH BY Abigail Miller and Stewart Cauley

ADDITIONAL PHOTO RESEARCH BY Elisa Taber

Contents

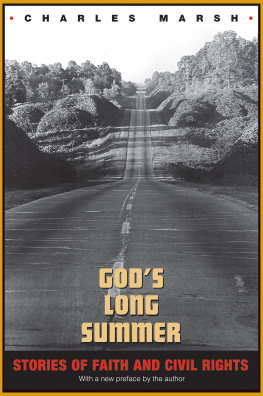

Road running into the town of Yazoo, Mississippi, 1964.

BEFORE

MISSISSIPPI AT A CROSSROADS

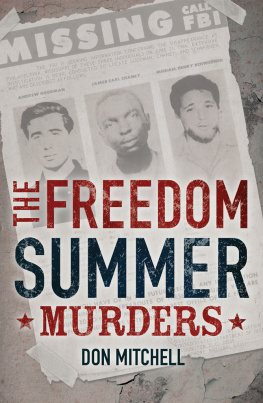

ON HALLOWEEN NIGHT, A STUDENT FROM YALE University in Connecticut stopped for gas in Port Gibson, Mississippi. A hundred years earlier, during the Civil War, Union troops had entered Mississippi through this same town. Now, in the eyes of local people, a new invasion had begun. Like the Union troops, the new invader was a Yankee, a northerner. He was easy to spot: a white, blond-haired stranger in a car with a black man and woman.

Four local men took action. They ordered the white man out of the car, beat him to the pavement, then circled, kicking and pounding. After the bloodied man was finally allowed to climb back into the car, the thugs followed it for miles along dark roads.

Two days later, two of the strangersthe white man and the black manwere spotted driving north out of the town of Natchez. A shiny green Chevy Impala with two white men in it pulled up behind their car. They made a U-turn, but the Chevy followed, riding their bumper. Heading south past farms and fields, the two cars sped up. Each time the first car roared ahead, the Chevy stayed on its tail. Engines groaning, gravel flying, soon the cars topped a hundred miles an hour. Finally, the Chevy pulled even and forced the strangers car into a ditch.

This time the locals had a gun. They ordered the driver to get out. He hesitatedthen punched the gas. The car lurched back onto the road. A bullet shattered the rear window. Another tore into a side panel. A third grazed a rear tire. The driver kept going and managed to duck down a side road as the green Chevy roared past.

It was November 1963. In Washington, D.C., the nations capital, President John F. Kennedy was not thinking about Mississippi. He was wondering whether he should pull the United States out of the Vietnam War. We will never know what Kennedy might have done, because an assassins bullet ended his life later that month in Texas. Something else happened that month that changed the future. For one weekend in Mississippi, thousands of bone-poor citizens gave America a long-overdue lesson.

A Lesson in Democracy

The two men whod been attacked and shot were Freedom Election volunteers. They and others like them were working to get black citizens of Mississippi registered to vote. Many black Mississippians had never votedmostly out of fear. When slaves were freed after the Civil War, they had voted in great numbers, but in 1890 this basic right was taken away. Mississippi and other Southern states passed laws requiring blacks to pay poll taxesthat is, to pay in order to vote. Few could afford such taxes. Other laws forced any black person who tried registering to vote to pass a reading test, or to interpret part of the state constitution. Blacks who still insisted on registering had their names published in the paper. They were then beaten, or had their homes shot into at night. By 1964, just 7 percent of blacks in Mississippi could vote.

But an election was coming that would decide the states next governor. Everyone knew that Paul B. Johnson would win the election. His father had been governor before him. White voters liked him. Johnson firmly supported segregation, the web of laws and practices that separated people by race and made African Americans second-class citizens. And he stood firmly against integration, the movement to make blacks and whites equal under the law, with the same rights to use schools and other public institutions. Johnson literally stood against integration. As lieutenant governor, the second highest office in the state, he had physically blocked a black man from entering the state university.

Mississippi had a long history of racial division and violence, as you will see in peace to driving cars too heavy for their license plates. Roughed up or just told to get out of town, the out-of-state students got a taste of how Mississippi law worked in 1963.

The terror nearly succeeded. The organizers of the Freedom Election had hoped that 200,000 African Americans would cast Freedom Votes in their churches, cafes, barber shops, and pool halls. This Freedom Election would be separate from the official state election, but under an old law, the parallel ballots of the Freedom Election would be legal. They might be used to challenge the results of the official election.

In the end, after police seized some of the Freedom Election ballots, black Mississippians had cast 82,000 votes. Not enough to keep Johnson from becoming the states new governor, but each vote was a sign of change in Mississippi. Bigger changes were coming. Mississippi stood at a crossroads.

Its Going to Take an Army

A few months before the Freedom Election in Mississippi, a quarter of a million people in the nations capital had heard Martin Luther King Jr. talk about his dreamthat someday the United States would live up to the promise in its Declaration of Independence that all Men are created equal. Prejudice against African Americans existed across the country, but racism reached its peak in the South. Everyone knew where it was worst. Roy Wilkins, the head of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), had said, There is no state with a record which approaches that of Mississippi in inhumanity, murder, brutality, and racial hatred. It is absolutely at the bottom of the list.