www.upress.state.ms.us

Designed by Peter D. Halverson

The University Press of Mississippi is a member of the

Association of American University Presses.

Original text 1965, by Misseduc Foundation, Inc. Reprinted by the University Press

of Mississippi 2017 by permission of Elisabeth Sifton and Hodding Carter III.

Compiled by the Council of Federated Organizations.

Introduction copyright 2017 University Press of Mississippi

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

First UPM printing 2017

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Niebuhr, Reinhold, 18921971, writer of foreword. | Carter, Hodding, writer of introduction. | Ward, Jason Morgan, writer of introduction.

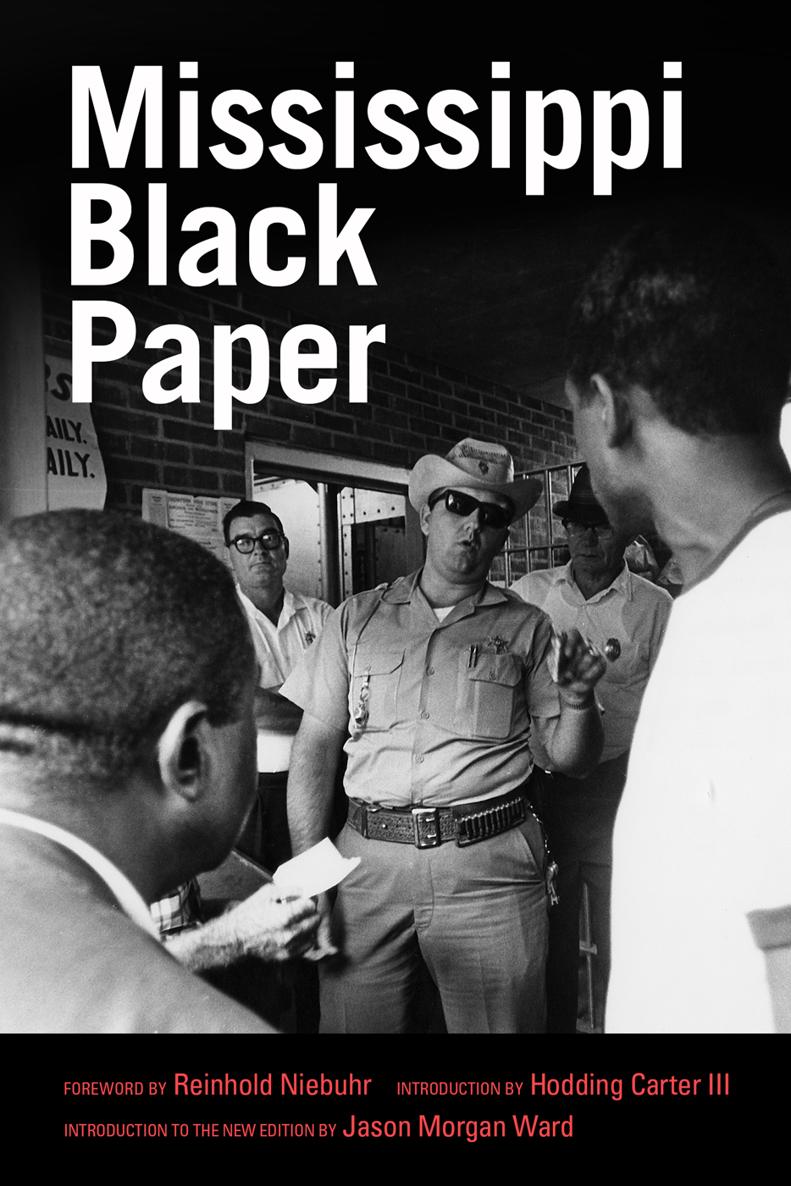

Title: Mississippi black paper / foreword by Reinhold Niebuhr; introduction by Hodding Carter III; introduction to the new edition by Jason Morgan Ward.

Description: Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, [2017] | Series: Civil rights in Mississippi | Original text 1965, by Misseduc Foundation, Inc. Reprinted by the University Press of Mississippi 2017 by permission of Elisabeth Sifton and Hodding Carter III. Introduction copyright University Press of Mississippi 2017ECIP title page. | Identifiers: LCCN 2017022083 (print) | LCCN 2017023715 (ebook) | ISBN 9781496813442 (epub single) | ISBN 9781496813459 (epub institutional) | ISBN 9781496813466 (pdf single) | ISBN 9781496813473 (pdf institutional) | ISBN 9781496813428 (cloth : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781496813435 (pbk : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Police brutalityMississippi. | ViolenceMississippi. | PoliceMississippi. | Law enforcementMississippi. | African AmericansMississippi.

Classification: LCC HV8145.M7 (ebook) | LCC HV8145.M7 M57 2017 (print) | DDC 323.1196/073076209046dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017022083

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data available

Introduction to the New Edition

IN EARLY FEBRUARY 1964, GREENE BREWER PULLED OVER AT A COUNTRY store in Tallahatchie County, Mississippi, to put air in a tire. Along with his younger brother Charles, who had moved to Indianapolis three years earlier, the twenty-nine-year-old New Jersey resident had returned home to visit family and friends. While Greene filled the tire, Charles went into Huntlys Grocery to buy some soft drinks. Hearing a commotion inside the store, Greene Brewer headed for the door. When he entered the store, he saw his brother bleeding and unconscious on the floor. As Brewer tried to drag his brother out of the store, a white man named George Little bludgeoned him with an axe handle. Despite suffering a fractured skull, cracked jawbone, broken nose, and burst eyeball, Greene Brewer somehow managed to load his brother into the car and drive off.

After delivering his injured younger brothers to a local hospital, Percy Lee Brewer went to see a white attorney. He said he wished he could help, the farmer later noted in a sworn affidavit, but that it would be a knock on him. As a member of the diehard segregationist Citizens Council, the attorney wanted nothing to do with the negro problemdespite the fact that the Brewer brothers had no history of civil rights activism. The provocation for the attack, as Charles Brewer recounted after regaining consciousness, was his failure to sir the storeowner when he purchased his sodas. When a damn nigger goes North and comes back, the proprietor spat, he gets beside himself, and he gets where he cant respect white folk. A different version of the incident had reached the county sheriff, who was even less sympathetic to Percy Brewers appeal on behalf of his hospitalized brothers. They are luckythey are supposed to be dead, Sheriff Ellett R. Dogan replied, Because of them coming in cussing. Left with no alternative, and a $212 hospital bill, Percy Brewer headed north to Clarksdale to contact the NAACP.

Four months after the attack, Greene and Percy Brewer traveled to the nations capital with a busload of black Mississippians. On June 8, 1964, at a public hearing organized by allies of the Council of Federated Organizations

Unlike many of the black Mississippians who testified at the National Theater in June 1964, Greene Brewers name does not appear in Mississippi Black Paper. Along with a handful of other individuals whose testimonies are published in the book, Brewer could not be reached for permission at the time of publication. Rather than omit powerful accounts from those who had movedpresumably for obvious reasons, the publisher printed Brewers story anonymously. The supporting statements from his family members, along with approximately two hundred additional affidavits collected by COFO and its allies, did not make the final list of fifty-seven testimonies included in the Mississippi Black Paper. Yet the broader effort to collect and document these accounts, distilled into book form in early 1965, reflects both the immediate strategic significance of racial violence in the development of the Mississippi civil rights movement and the historical importance of such testimony to the black freedom struggle. By bearing witness to white terrorism and abuse of power in Mississippi, Greene Brewer and dozens of othersmany of whose names barely register in a survey of the existing literature on Mississippis civil rights sagadefied the culture of silence and suppression that perpetuated Jim Crow. Their testimony did not dynamite the pillars of brutality, terror, complicity, and denial that propped up Mississippis white supremacist regime, but collectively these accounts helped shape a national conversation on the fundamental violence of Mississippis segregated social order.

Greene Brewers name may have been lost to history, or at least overshadowed by the hundreds of black Mississippians written into the states civil rights story, but his testimony highlights some of the important themes and questions raised in Mississippi Black Paper. First, the brutal attack he and his brother endured serves as a reminder that seemingly isolated incidents of racial violence could assume world-historical significance. In the same corner of the Mississippi Delta where an earlier encounter at a country store cash register sparked the most famous lynching in American history, the Brewers found themselves pulled into the civil rights struggle via white supremacists volatile anxieties. Emmett Till would have been nearly the same age as Greenes younger brother Charles. Whites deemed both suspect on account of their time up North, and neither victims family could expect any semblance of justice in Tallahatchie County. Separated by nearly a decade, these two incidents of violence resulted in vastly different levels of publicity and notoriety. Yet they serve as a reminder that regardless of how little Tallahatchie Countyand Mississippihad changed between 1955 and 1964, local whites responded violently precisely because they understood the gathering threats to the racial status quo.

Indeed, despite the seemingly random nature of the attack on the Brewer brothers, anti-black violence had a logic and rationale that preceded Freedom Summer and persisted in its wake. While Freedom Summer and the violence it provoked feature prominently in