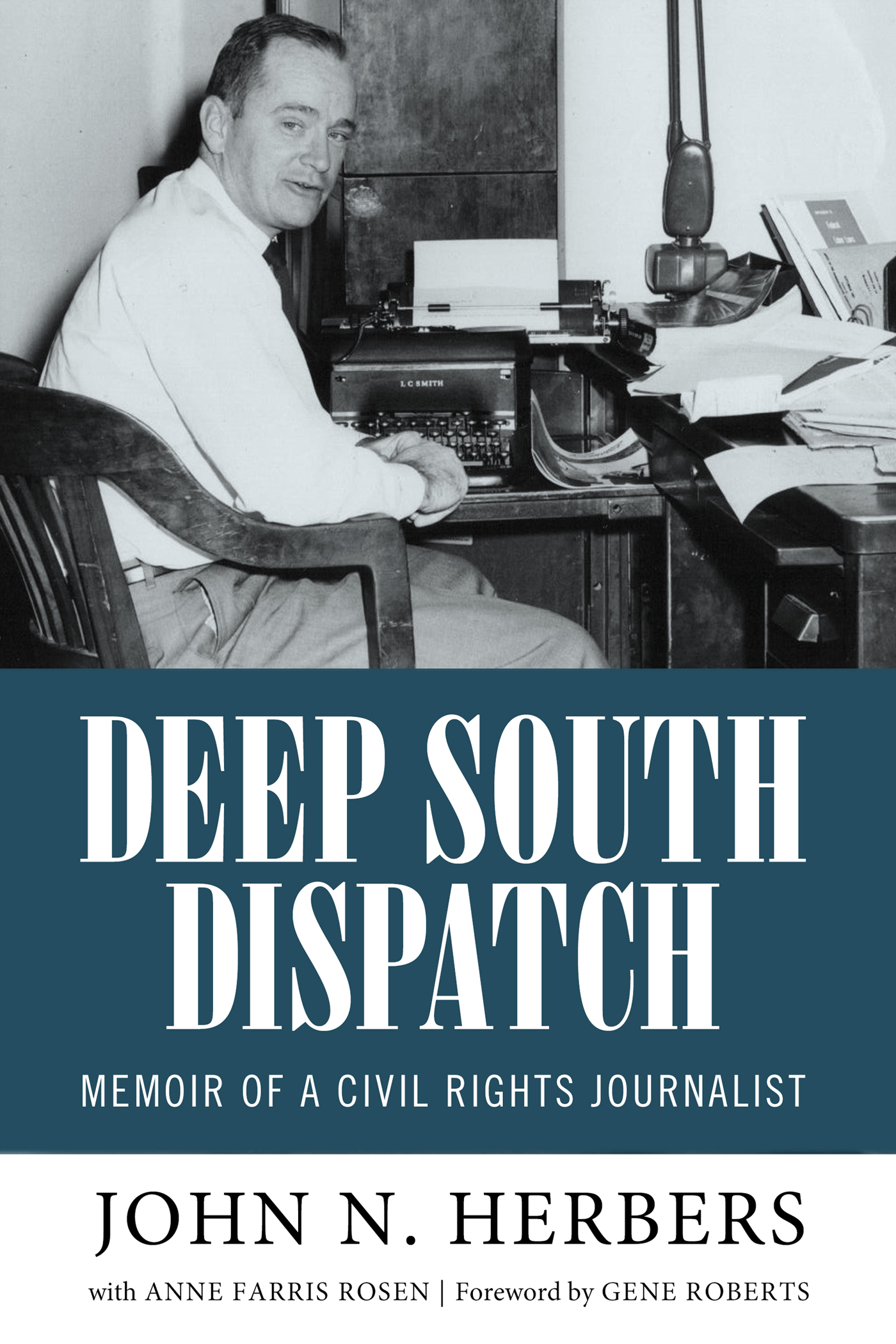

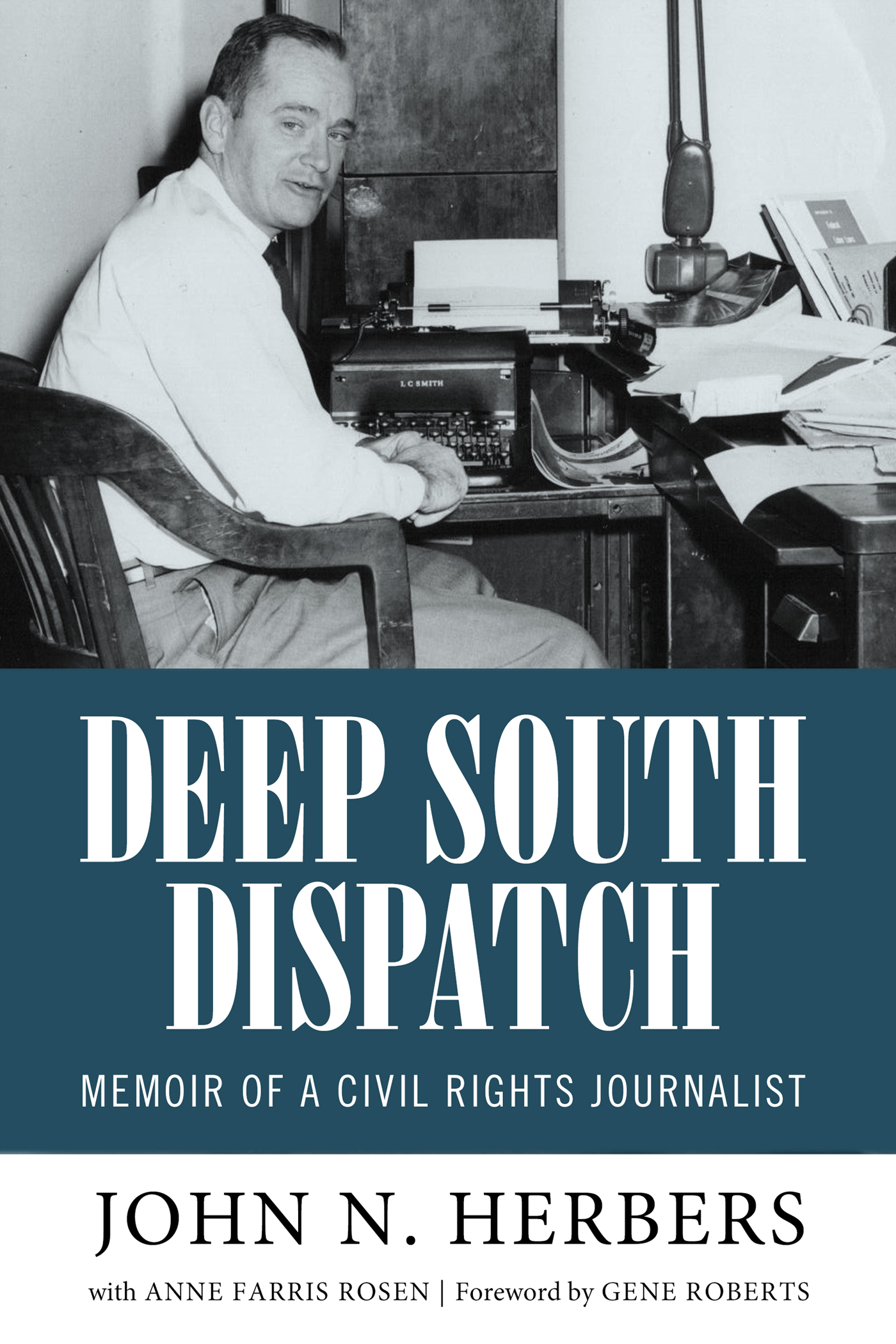

DEEP SOUTH DISPATCH

DEEP SOUTH DISPATCH

MEMOIR OF A CIVIL RIGHTS JOURNALIST

JOHN N. HERBERS

with ANNE FARRIS ROSEN | Foreword by GENE ROBERTS

University Press of Mississippi / Jackson

Willie Morris Books in Memoir and Biography

www.upress.state.ms.us

Designed by Peter D. Halverson

The University Press of Mississippi is a member of the Association of American University Presses.

Copyright 2018 by University Press of Mississippi

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States

First printing 2018

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Herbers, John, author. | Rosen, Anne Farris, author.

Title: Deep South dispatch : memoir of a civil rights journalist / John N. Herbers with Anne Farris Rosen ; foreword by Gene Roberts.

Description: Jackson : University Press of Mississippi, [2018] | Series: Willie Morris books in memoir and biography | Includes bibliographical references and index. |

Identifiers: LCCN 2017049188 (print) | LCCN 2017050504 (ebook) | ISBN 9781496816757 (epub single) | ISBN 9781496816764 (epub institutional) | ISBN 9781496816771 (pdf single) | ISBN 9781496816788 (pdf institutional) | ISBN 9781496816740 | ISBN 9781496816740 (cloth : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Herbers, John. | JournalistsSouthern StatesBiography. | Civil rights movementsPress coverageSouthern States.

Classification: LCC PN4874.H47 (ebook) | LCC PN4874.H47 A3 2018 (print) | DDC 070.92 [B]dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017049188

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data available

Contents

Foreword

JOHN HERBERS WAS ONE OF AMERICAS MOST IMPORTANT NEWS REPORTERS in the second half of the twentieth century. Few, if any, covered as many important stories as solidly or as vividly as Herbers.

First for United Press International, then the New York Times, he was present with his notebook at an astonishing array of journalistic hot spots. He sat in a tense courtroom for days reporting the iconic trial of the murderers of Emmett Till, a fourteen-year-old black boy who was beaten and shot to death by two Mississippi white men and thrown in a river because he may have whistled at a white woman. Herbers also chronicled the rise of the White Citizens Councils in Mississippi as they marshaled economic pressure against school desegregation and black voter registration.

Later, while working at the Times, he rushed to Dallas just hours after President John F. Kennedy was assassinated and as federal and state lawmen searched frantically for the shooter. In Birmingham, Alabama, he raced to the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church just minutes after a bomb shook the building and watched in horror, thinking of his own daughters, as the bodies of four young black girls were pulled from the wreckage. In St. Augustine, Florida, he watched angry whites roam the streets and attack civil rights demonstrators at will, pouring muriatic acid into a swimming pool to prevent blacks from using it. At the first Byron De La Beckwith trial for the assassination of NAACP leader Medgar Evers, he carefully recorded the exchange when the district attorney asked a potential white juror if he thought it was a crime for a white man to kill a black man in Mississippi. What was his answer? the judge asked after a long silence; and then came the reply from the district attorney: Hes thinking it over.

Herbers endured the long Mississippi Freedom Summer of 1964 in which hundreds of out-of-state students swept into Mississippi to confront white supremacy head on, and almost immediately three civil rights organizers were slain and their bodies hidden in an earthen dam. He watched as FBI agents and one of the suspected killers unearthed the bodies. Few reporters had more exposure to Martin Luther King Jr. than Herbers, who reported on him from Atlanta to Birmingham to Mississippi and finally for weeks at Selma, Alabama, as diehard segregationists attacked demonstrators so viciously that they paved the way for the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Toward the end of the Selma movement, the Times transferred Herbers to Washington, DC, where he became a key player in the papers Washington bureau, covering the Watergate turbulence and the administrations of six presidents.

I am in a unique position to assess Herberss brilliance and acumen. I succeeded him in 1965 as the New York Times chief southern correspondent when he was transferred to Washington. I read and reread his stories in the Times files, followed in his footsteps to several civil rights battlegrounds, and marveled at the quantity and quality of his coverage and at his courage. White mobs heckled him. He was repeatedly threatened.

Clearly, Herbers had a story to tell, although he waited until late in his ninety-three-year life to do it; but then, with assistance from his daughter, Anne Farris Rosen, he focused on his southern reporting years with a heres-what-I-saw-and-heard narrative that speeds you through the chapters. He died early in 2017 on the eve of the funeral of his beloved wife, Betty. His book had been written and accepted by the University Press of Mississippi at the time of his death but not yet printed.

Future historians and anyone who wants to know more about the civil rights years can be grateful, indeed, that John and Anne raced with death to complete the manuscript. Its quite a book. And it could not be more timely as the nation now witnesses another period of racial upheaval. Never have Herberss writings been more critical and immediate than since he first penned them. His historical retrospectiveeerily similar to today in many respects when he describes the rise of white supremacy groups and race-baiting diatribes by white leadersprovides us with a deeper understanding of Americas constant struggle to achieve racial equity.

How did Herbers become the man he was? The book is also a personal journey, a poignant coming-of-age story about a young mans struggle as he questions his southern heritage and the prescribed laws and mores of a segregated society in the 1950s and 1960s. How did a skilled and exceptionally gifted reporter emerge from a depression-wracked Mississippi household where the prevailing wisdom was that blacks were put on earth to be servants to whites? The short answer: by degrees. John goes from high school into the army upon graduation, and in the midst of World War II, thanks to good army libraries, he becomes a serious reader. After the war he enrolls at Emory University in Atlanta and joins the staff of a student newspaper, where two other students also go on to become journalists who write about civil rightsClaude Sitton for the New York Times and Reese Cleghorn for the Atlanta Journal and the Charlotte Observer.

After college graduation in 1949, Herbers headed for Mississippi, not because it was a potential site of racial turmoil but because it was home; his parents were growing old and they needed him. He landed a job on the Morning Star in Greenwood, Mississippi, and then on the Jackson Daily News. Even though the US Supreme Courts school desegregation decision was still three years away, he became aware that race was rising to a low boil in Mississippi. It was apparent even at the Daily News, where racism was permeating the building as surely as the smell of printers ink. He was feeling uncomfortable with both the papers tone and with his low pay when, in 1952, he married his girlfriend, Betty, and jumped to the three-person United Press Jackson bureau for a five-dollar increase in weekly salary.

Next page