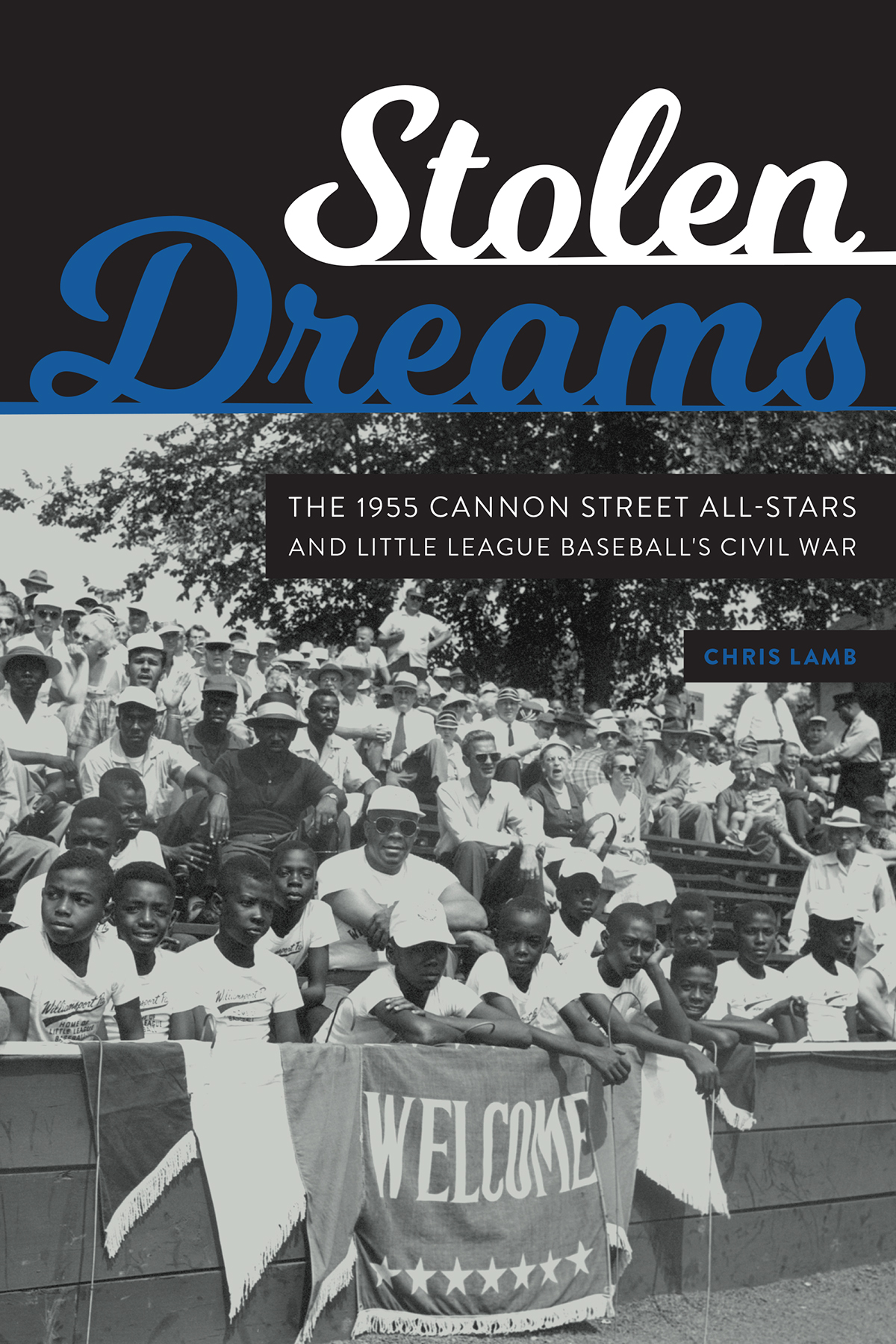

[Stolen Dreams] meticulously documents an important moment, and team, that few people will know but should. Its about the collision of racism and baseball, years after Jackie Robinson broke the color barrier, and shows just how far Blacks had left to go to be accepted in Americas pastime. Lamb writes this story with affection, grace, and skill.

Mike Freeman, editor of race and inequality at USA Today

Chris Lamb takes a forgotten baseball tournament and a forgotten moment in the civil rights struggle and spins them into an unforgettable story, proving, as Martin Luther King Jr. might have said, that the long arc of a batted ball bends toward justice. With impressive research and sharp insight, Lamb illustrates once again the important role baseball plays in understanding and shaping American culture.

Jonathan Eig, best-selling author of Opening Day: The Story of Jackie Robinsons First Season

Sports is a brilliant and bracing window for understanding Jim Crow segregation in the South. With this book, Chris Lamb uncovers a narrative in this history that few readers will know: a history of racism, injustice, baseball, and the kids crushed by the hatreds of adults. I cant recommend this book enough. It speaks to the past brilliantly, but it also speaks to our troubled present. A necessary and important read.

Dave Zirin, author of The Kaepernick Effect: Taking a Knee, Changing the World

Lamb has presented Little League Baseball as a microcosm of Jim Crowism with so many history lessons of shame, sadness, and racial injustices propagated by the white majority. Lamb fires cannon shots with explosive narratives about Octavius Catto, Judge J. Waties Waring, Isaac Woodard, Robert Morrison, Robert Small, Frazier B. Baker, and others. This narrative is one of the most comprehensive examinations of the Lost Cause obsession for control in America.

Larry Lester, Negro League Baseball historian and author

Chris Lambs thorough and eloquent account embodies the best tradition of civil rights scholarship, exposing Americas long history of racism, particularly in Charleston, a city built literally on the backs of enslaved people. Redemptive at its core, Stolen Dreams reminds us of all of the importance of telling the stories of African Americans that have so often been erased, forgotten, or neglected.

Marjory Wentworth, South Carolina poet laureate, 200320

Stolen Dreams

The 1955 Cannon Street All-Stars and Little League Baseballs Civil War

Chris Lamb

University of Nebraska Press | Lincoln

2022 by Chris Lamb

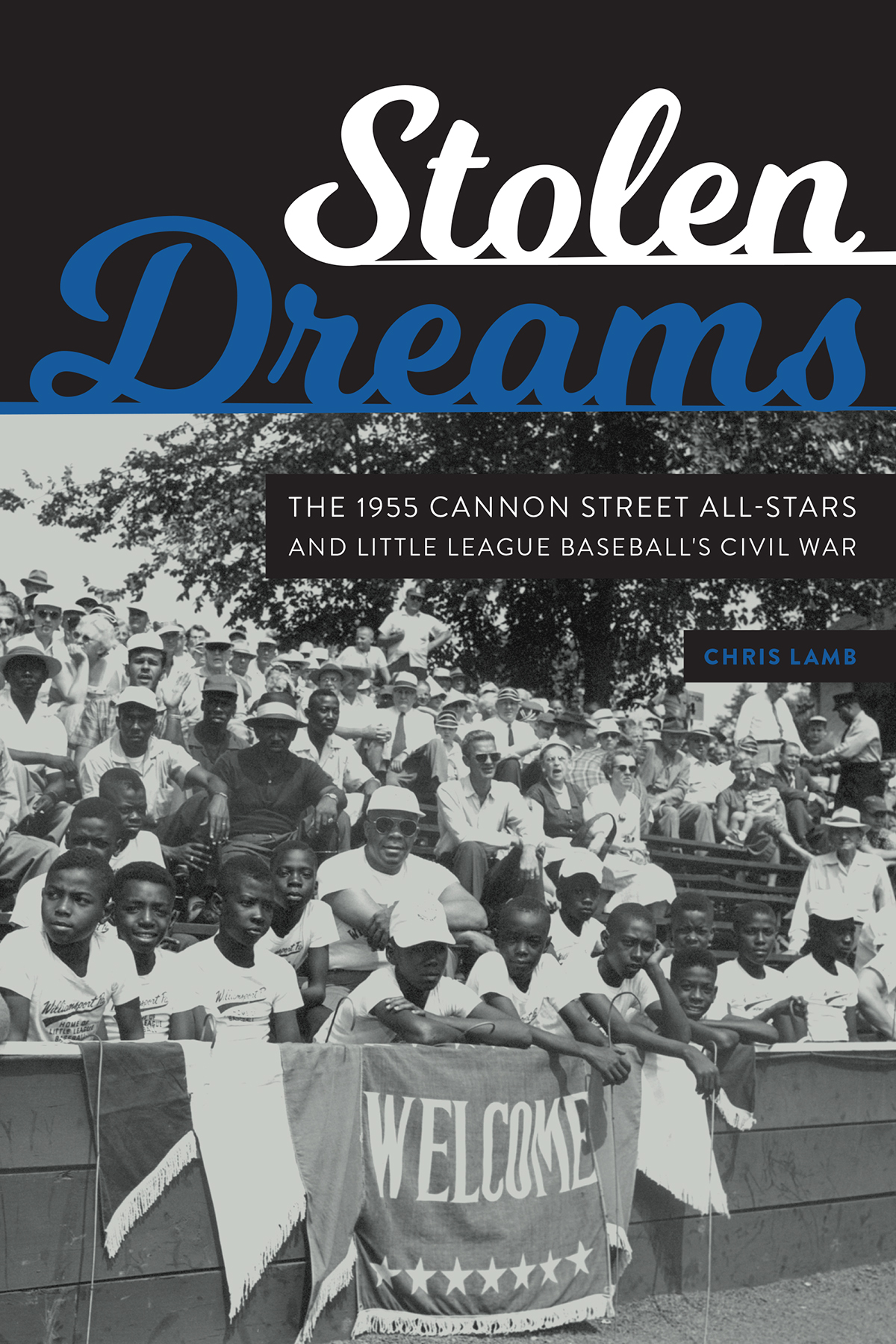

Cover designed by University of Nebraska Press; cover image is from the interior.

Author photo Liz Kay.

All rights reserved

The University of Nebraska Press is part of a land-grant institution with campuses and programs on the past, present, and future homelands of the Pawnee, Ponca, Otoe-Missouria, Omaha, Dakota, Lakota, Kaw, Cheyenne, and Arapaho Peoples, as well as those of the relocated Ho-Chunk, Sac and Fox, and Iowa Peoples.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2021030586

The publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

This book is dedicated to Augustus Holt, 19462020

And to the Cannon Street YMCA All-Stars

And to my parents,

Robert Lamb, 19232020

Jean Lamb, 19252016

It was a long time ago.

I have almost forgotten my dream.

But it was there then,

In front of me,

Bright like a sun

My dream.

And then the wall rose,

Rose slowly,

Slowly,

Between me and my dream.

Rose until it touched the sky

The wall.

Shadow.

I am black.

I lie down in the shadow.

No longer the light of my dream before me,

Above me.

Only the thick wall.

Only the shadow.

My hands!

My dark hands!

Break through the wall!

Find my dream!

Help me to shatter this darkness,

To smash this night,

To break this shadow

Into a thousand lights of sun,

Into a thousand whirling dreams

Of sun!

Langston Hughes, As I Grew Older (1925)

Contents

I met Gus Holt in Charleston, South Carolina, in 2012, when I was teaching journalism at the College of Charleston.

Historian Steve Hoffius, a mutual friend, told me about the 1955 Cannon Street All-Stars and suggested I write their story. I had never heard of the team. Steve introduced me to Gus. Gus and I then met at the colleges library. He came to our meeting with several folders full of research. Gus and I probably met a dozen times over the years and he almost always brought research with him.

I received my PhD more than twenty-five years ago, and Ive been a college professor longer than that. Gus, who had a high school diploma, was a better researcher than a lot of people with PhDs. He was intrepidas a researcher and as a man, whether he was challenging bigotry in the East Cooper Recreation Department, organizing reunions for the Cannon Street All-Stars, urging reporters to tell the teams story, reviving Little League Baseball in Charleston, or struggling with the overwhelming health issues of loved ones or the health issues that eventually took his own life.

This is the story of the 1955 Cannon Street All-Stars. But it is really Guss story, even though he didnt live to see the publication of the book. Gus brought the story back to life and willed it into something that transcended the saga of eleven- and twelve-year-olds being denied the chance to play baseball because of the color of their skin. Gus understood what I finally understood myself: The Cannon Street All-Stars are part of a much larger story of how racial bigotry poisoned the people of Charleston and so many others since the arrival of the first slave ship. People continue to suffer and die every hour of the poison of bigotry because much of white America denies the existence of this virulent virus. This virus is particularly toxic among children because it takes away their dreams, as Langston Hughes wrote about in his poem HarlemA Dream Deferred.

I initially told Gus I wasnt interested in writing the book. I was working on other books. I would be leaving Charleston soon to take a job at Indiana UniversityPurdue University at Indianapolis. There would be so many other things gnawing at my time.

But when I got to Indianapolis, I couldnt get the story out of my head.

Trey Strecker, then the editor of Nine: A Journal of Baseball History and Culture, asked me to give the keynote speech at Nines spring-training conference. I talked about the Cannon Street team. I kept getting deeper into the story. I met Mike Lennox, the executive director of Play Ball Indiana, an affiliate of RBI , Reviving Baseball in the Inner Cities, which gives boys and girls the opportunity to participate in baseball and softball. Mike asked me to talk about the Cannon Street All-Stars during a fundraising for the organization.

Whenever my wife, Lesly, son, David, and I went to see my in-laws, Dan and Eleanor Jacobs, in Charleston, I went to the Avery Research Center, which includes archives of the Black experience in Charleston, and to the South Carolina room of the Charleston County Public Library, where I looked at 1955 newspaper articles about the Cannon Street All-Stars. I often met with Gus, who kept asking me questions. If I didnt know the answer or if I answered incorrectly, he would stare at me in disbelief. I finally got to the point when I could answer his questions, and his stare turned to a smile as he said, You got it.