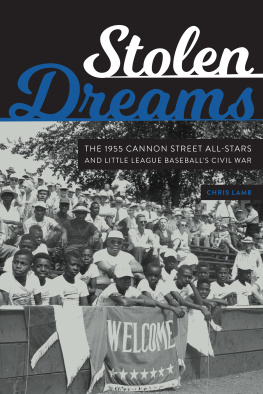

LET THEM PLAY

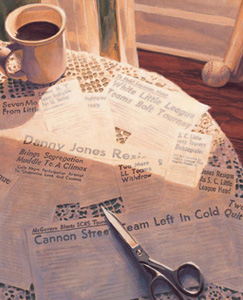

Segregated South Carolina, 1955: There are 62 official Little League programs in South Carolinaall but one of the leagues are composed entirely of white players. From Charleston, the all-black Cannon Street YMCA All-Stars team is formed in the hopes of playing in the states annual Little League Tournament.

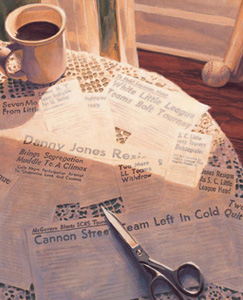

What should have been a game between children becomes a segregation quagmire when adult prejudice leads all of the white teams to pull out of the official Little League program rather than play against the Cannon Street All-Stars. This boycott gives the Cannon Street team a legitimate spot in the Little League Baseball World Series held in Williamsport, Pennsylvania. While the Cannon Street team is invited to attend the World Series game as guests, they are not allowed to participate since they have not officially played and won their states tournament.

Author Margot Theis Raven recounts this true story of spirit and determination from Americas early civil rights history. The title takes its name from the chant shouted by the spectators who attended the World Series final.

LET THEM PLAY

BY MARGOT THEIS RAVEN

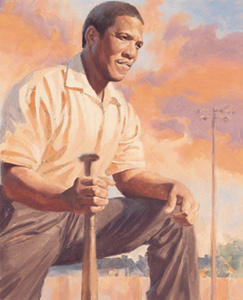

ILLUSTRATED BY CHRIS ELLISON

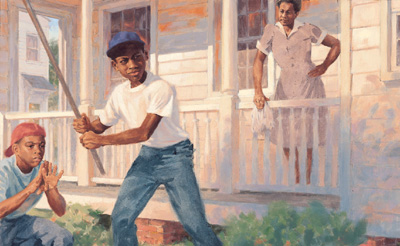

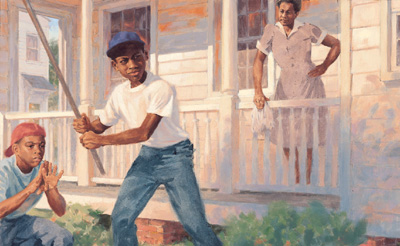

Most folks say it was Coach Ben Singleton who pulled the all-star dreams from the sky over Harmon Field and sprinkled them in the eyes of 14 boys the summer of 1955. Not that baseball dreams werent already rising high as heat waves on noonday porches all over Charlestons Upper Westside.

Boys wanted to be Jackie Robinson playing for the Brooklyn Dodgers, and mothers like Flossie Bailey on Strawberry Lane wanted to find their missing mop handles. Stickball players like her son John used the handles as bats to hit half-rubber balls, and sandlot players made mitts from paper bags or cardboard sewn with shoelaces.

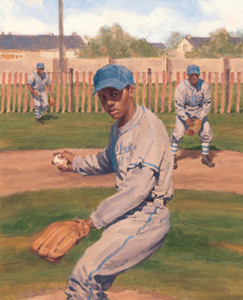

But every street and sandlot player knew the lucky boys suited up for one of the four Little League teams chartered by the Cannon Street YMCA. Those boys used real bats, balls, and gloves and wore real uniforms. They played on Harmon Field, too, a sun-spit patch of earth where the players rolled out a red picket fence before each game to mark the home run line!

That Jackie Robinson summer, it wasnt just Charlestons Westside boys that loved playing ball. Baseball fever burned all over South Carolina. The state had 62 chartered Little Leagues in allbut only the Cannon Street league was black. All the other leagues were white.

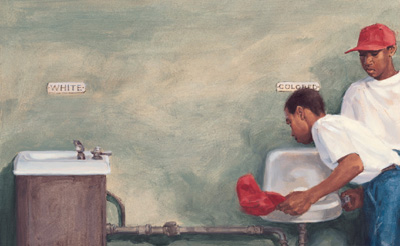

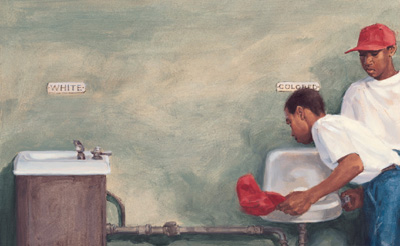

In South Carolina in 1955, no white Little League team ever played a black team, because white people and black people were said to live separate but equal. That meant black people had to use separate schools. Separate parks. Separate ball fields, too-even though every chartered Little League team signed a paper to play any team regardless of race, color, or creed.

But that summer, like blue crabs tucked deep in the mud banks of Charlestons marsh creeks, parents, neighbors, and coaches tried to keep the dark troubles and deep worries of the times from the Westside boys who just wanted to play baseball. And the more baseball the better!

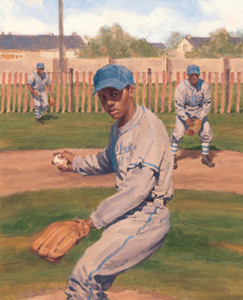

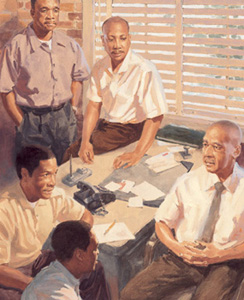

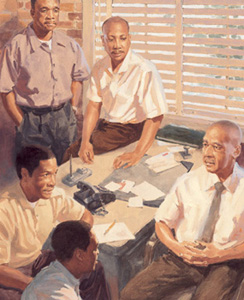

One day, in the small front room where Mr. Robert Morrison, president of the Cannon Street YMCA, made important decisions, Coach Singleton and the other coaches met to pick the first all-black Little League all-star team in South Carolina. Called the Cannon Street All-Stars, the team would compete in the city tournament, and then could advance to the state competition, and then to the regional tournament in Rome, Georgia. If they won there, it was off to the Little League World Series in Williamsport, Pennsylvania!

Coach Singleton hit the exciting idea to the 14 chosen boys like a high pop fly! Big Maj, can you pitch an extra tournament game? he grinned. Leroy Major grinned back!

Soon all-star dreams sparkled in Westside parents eyes: Mothers held teas as fund-raisers to buy uniforms, making heaps of fried chicken, sweet johnnycakes, and bread pudding that melted in your mouth, set out on best linens and good china. Fathers who worked at the Navy Yard went straight to the ball field to help out. Nothing was too good for the boys!

But the dark fears hidden from the boys bubbled to light when the states Little League director heard that white all-star teams must compete against an all-black team.

He said: No white team would play Cannon Street. Not in Charleston or anywhere! The director withdrew from Little League to start his own boys baseball program. He encouraged state teams to boycott Little League, too. Like a dream gone nightmare, every white South Carolina Little League joined the new baseball program. The boycott eventually spread through 11 southern states, making Cannon Street the only Little League franchise left in the South, and the All-Stars became the team nobody would play.

Even though the Cannon Street boys were the state winners and Southeastern Champs, they had won by default. They had not played a single game to advance to the Little League World Series. Officials in Williamsport ruled the boys could not compete in the final tournament.

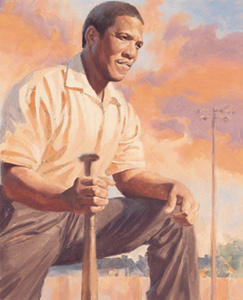

Mid-August on Harmon Field, 14 boys watched Ben Singleton thump a bat on a bench at sundown. Thump, thump, Ben drummed, trying to find the right words. He had seven children of his own, including his son, Maurice, second baseman on the All-Stars team, but he loved every one of these fine boys as if they were his own. He wanted them to stay fine. He knew the man you condemn today is the one you become tomorrow.

Boys, Ive got news, he finally spoke. Little League has invited us as official guests to the World Series in Williamsport. They say theyll treat you like the other play-off teams. And I promise youll be met by fire trucks and cheering people, he added.

But he didnt promise the boys that they would play.

Still he hoped that when they got to Williamsport, he and the other coaches could persuade Little League President Peter McGovern to let the boys take the field for at least one game.

On the day of the trip, mothers packed clean clothes and new pajamas for the boys stay in a real college dorm! Flossie Bailey filled a food hamper with johnnycakes and ham sandwiches for her son Johns long bus ride.

That evening, the boys and mencoaches, managers, and YMCA officialsmet by a blue bus at the YMCA. The bus was old and battered, but it seemed like a rocket ship to Mars to the boys. For most of them it was their first trip out of South Carolina.