The Last

Best League

Copyright 2004 by James Collins

10th Anniversary Edition Afterword 2014 by James Collins

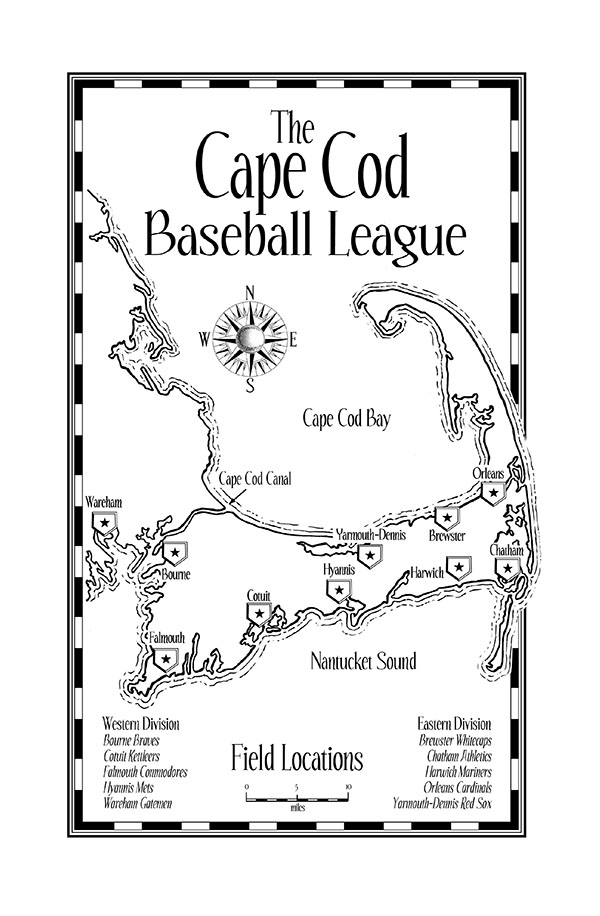

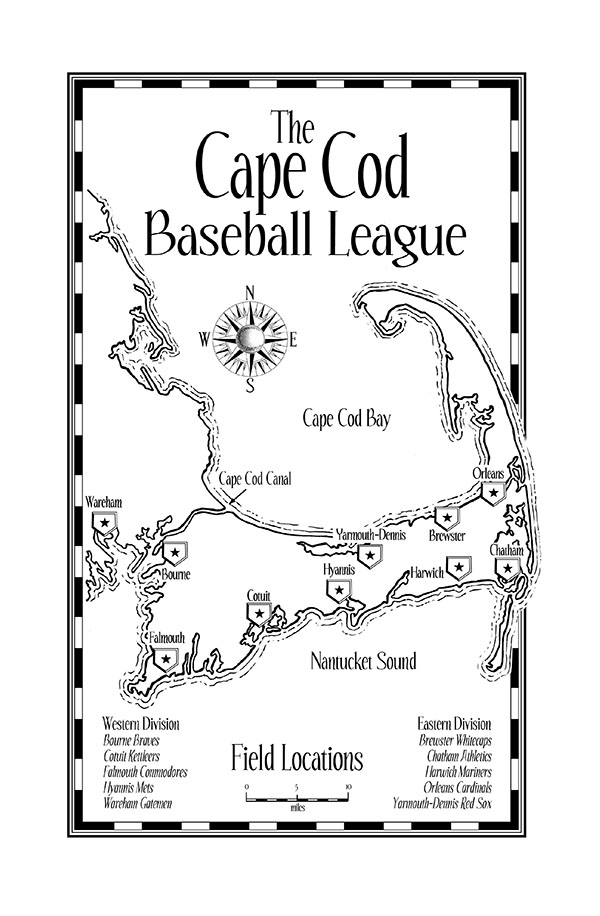

Map by Erick Ingraham

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. For information, address Da Capo Press, 44 Farnsworth Street, 3rd Floor, Boston, MA 02210.

Designed by Brent Wilcox

Typeset in New Caledonia

Cataloging-in-Publication data for this book is available from the Library of Congress.

First Da Capo Press edition 2004

Paperback edition 2005

ISBN: 978-0-306-82311-4 (e-book)

Published by Da Capo Press

A Member of the Perseus Books Group

http://www.dacapopress.com

Da Capo Press books are available at special discounts for bulk purchases in the U.S. by corporations, institutions, and other organizations. For more information, please contact the Special Markets Department at the Perseus Books Group, 2300 Chestnut Street, Suite 200, Philadelphia, PA, 19103, or call (800) 810-4145, ext. 5000, or e-mail .

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

FOR KRISTEN

Contents

I FIRST HEARD OF THE CAPE COD BASEBALL LEAGUE when I was an infielder at Dartmouth College in the early 1980s. Players didnt use the leagues formal name, but, rather, talked wistfully about playing on the Cape, as if some kind of aura surrounded the geography, itself. The league was the best of the NCAA summer leagues. We didnt know much about it or how someone went about getting into itthat was part of the Capes mystiquebut we knew that most of us had been team captains and all-stars and most valuable players in high school, and none of us was good enough to play there.

I spent my first college summer back home in Walpole, New Hampshire, playing on a team that attracted the most serious players within an eight- or ten-town radius, players who had gone on, mostly, to small northeastern colleges. Some noncollege guys played on the team as well. They worked their full-time jobs around the games, brought beer in the trunks of their cars, gave the eight-team league a rough, townie edge. Id been aware all along of the sorting taking place around me, and now I felt the pinch.

I had played with or against many of the players in Walpole beforewe stood at the tip of a local pyramid whose base stretched across a broad rural area, our talent or drive having lifted us higher than almost everyone wed played with on the way up. The winnowing, at the lower levels, had been clear, relatively painless, usually self-selected. Millions of kids start out dreaming of being big-league ballplayers. Most of them, at early ages, admit they dont have what it takes, or decide the game isnt worth the effort, or find some other passion to replace it. Dreams are fragile. But I had fallen in love with the game at eight years old, and from then on I wanted nothing more than to play second base for the Boston Red Sox.

Wanting to be a baseball player differed from wanting to be an astronaut or a policeman. I could actually work at becoming a baseball player, and I grew up believing I could will myself to the majors by working harder than anybody else. I was the kid who slept with his baseball glove, who shoveled snow off the driveway so I could play catch in the winter. I talked my parents into letting me go to baseball camps. My father, a Brit, didnt understand the sport. My mother knew only a little about it, but she loved watching my games, and both of them respected how much I wanted to be good at it. They bought me baseball books, reassured me, without really knowing, that I had a chance. When I was twelve years old I saw an ad in the back of a Baseball Digest and wrote away for information about how to become a major league ballplayer. I pored over the thick binder that arrived, memorizing the mimeographed pages of tips and exercises and descriptions of what scouts looked for in a prospect. Fortunately, I had a knack for the game. At each higher level I stood out, got picked for all-star teams.

And baseball changed me. I lived for the game, and made decisions based on how theyd affect my playing. I ate differently than the rest of my familyno soda, no junk food. I went to bed early without being told. I was a shy kid. I didnt like drawing attention to myself, except on a baseball field. There I took charge, felt the confidence that comes from being looked up to, admired, singled out.

Only one other talented player in my class shared the same dream. Jeff Hubbard and I had pushed each other ever since Little League. We practiced endlesslyI threw balls at his feet, he hit grounders just beyond my reach, to make me dive. Before games, we dressed together at Jeffs house, getting psyched up to the thump of Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers. We werent alike. I thought he was cocky, and I couldnt understand why he turned everything into a competition. I was quiet, serious, brooded over small failures. But we were best friends. His dad, who had been a star pitcher at the University of New Hampshire before throwing snowballs ruined his arm, took both of us to Winter Haven, Florida, each March to watch the Red Sox train for their upcoming seasonand to prepare us for ours. We stayed at the same hotel as the Red Sox players, ate in the same restaurants. In the evenings Jeff and I sneaked onto a perfectly groomed red-clay infield at the minor league complex and practiced fielding ground balls over and over and over until it became too dark to see them. We hopped the fence of an orange orchard beyond the outfield of Chain O Lakes Park and chased down home-run balls. We kept a milk crates worth so we could take our own batting practice with the real thing.

Jeff and I both played in collegea rare occurrence for athletes from our small townbut I knew, that first year, that Jeff had stepped out from the local pyramid and entered a much larger one. He was our best player and perennial all-star shortstop, and the only one missing from my summer team. Hed gone to the University of North Carolina on a baseball scholarship. In the summer he was playing on the Cape.

THE SUMMER BEFORE WE STARTED college was a powerful one, and I remember the way it ended.

My dream of playing professional baseball felt very close. I had been named the outstanding player in the previous years state American Legion tournament. I played second base for the strongest Legion team in the district, and Jeff played shortstop; the papers called us the best double-play combination in the state in years. Our coach told me that major league scouts had been asking about both of us.

I had gone on my first date with the smartest girl in my class, someone Id had a crush on for a long time. Wed driven an hour to a theater at Dartmouth, where I was headed that fall. Wed watched a performance of Richard III, and later, at her front door, wed kissed goodnight. The next day, on a sunny, hot, glorious afternoon, feeling invincible, I hung in too long turning a double play. Jeff was pitching in a tense, close game. The groundball up the middle got hung up in our shortstops glove. I floated over to the bag, planted my left leg, and waited until he found the ball and shuffled it to me. It arrived as the baserunner lowered his shoulder and crashed into the side of my left leg.

Something in my trajectory ripped apart as my knees ligaments tore, and I sensed in the hospital that any chance Id had of playing in the pros had disappeared. The surgeon prepared me for half a year of rehab, just to play again with a bulky knee brace.

Next page