GOOD TO

GREAT

Why Some Companies

Make the Leap ...

and Others Dont

JIM COLLINS

This book is dedicated to the Chimps.

I love you all, each and every one.

Contents

MEMBERS OF THE GOOD - TO - GREAT RESEARCH TEAM

ASSEMBLED FOR TEAM MEETING, JANUARY 2000

First row: Vicki Mosur Osgood, Alyson Sinclair, Stefanie A. Judd, Christine Jones

Second row: Eric Hagen, Duane C. Duffy, Paul Weissman, Scott Jones, Weijia (Eve) Li

Third row: Nicholas M. Osgood, Jenni Cooper, Leigh Wilbanks, Anthony J. Chirikos

Fourth row: Brian J. Bagley, Jim Collins, Brian C. Larsen, Peter Van Genderen, Lane Hornung

Not pictured: Scott Cederberg, Morten T. Hansen, Amber L. Young

Photo credit: J IM C OLLINS C OLLECTION.

A s I was finishing this manuscript, I went for a run up a steep, rocky trail in Eldorado Springs Canyon, just south of my home in Boulder, Colorado. I had stopped on top at one of my favorite sitting places with a view of the high country still covered in its winter coat of snow, when an odd question popped into my mind: How much would someone have to pay me not to publish Good to Great?

It was an interesting thought experiment, given that Id just spent the previous five years working on the research project and writing this book. Not that there isnt some number that might entice me to bury it, but by the time I crossed the hundred-million-dollar threshold, it was time to head back down the trail. Even that much couldnt convince me to abandon the project. I am a teacher at heart. As such, it is impossible for me to imagine not sharing what weve learned with students around the world. And it is in the spirit of learning and teaching that I bring forth this work.

After many months of hiding away like a hermit in what I call monk mode, I would very much enjoy hearing from people about what works for them and what does not. I hope you will find much of value in these pages and will commit to applying what you learn to whatever you do, if not to your company, then to your social sector work, and if not there, then at least to your own life.

Jim Collins

jimcollins@aol.com

www.jimcollins.com

Boulder, Colorado

March 27, 2001

The pagination of this electronic edition does not match the edition from which it was created. To locate a specific passage, please use the search feature of your e-book reader.

Chapter 1

Good is the Enemy of Great

Thats what makes death so hardunsatisfied curiosity.

B ERYL M ARKHAM ,

West with the Night

G ood is the enemy of great.

And that is one of the key reasons why we have so little that becomes great.

We dont have great schools, principally because we have good schools. We dont have great government, principally because we have good government. Few people attain great lives, in large part because it is just so easy to settle for a good life. The vast majority of companies never become great, precisely because the vast majority become quite goodand that is their main problem.

This point became piercingly clear to me in 1996, when I was having dinner with a group of thought leaders gathered for a discussion about organizational performance. Bill Meehan, the managing director of the San Francisco office of McKinsey & Company, leaned over and casually confided, You know, Jim, we love Built to Last around here. You and your coauthor did a very fine job on the research and writing. Unfortunately, its useless.

Curious, I asked him to explain.

The companies you wrote about were, for the most part, always great, he said. They never had to turn themselves from good companies into great companies. They had parents like David Packard and George Merck, who shaped the character of greatness from early on. But what about the vast majority of companies that wake up partway through life and realize that theyre good, but not great?

I now realize that Meehan was exaggerating for effect with his useless comment, but his essential observation was correctthat truly great companies, for the most part, have always been great. And the vast majority of good companies remain just thatgood, but not great. Indeed, Meehans comment proved to be an invaluable gift, as it planted the seed of a question that became the basis of this entire booknamely, Can a good company become a great company and, if so, how? Or is the disease of just being good incurable?

Five years after that fateful dinner we can now say, without question, that good to great does happen, and weve learned much about the underlying variables that make it happen. Inspired by Bill Meehans challenge, my research team and I embarked on a five-year research effort, a journey to explore the inner workings of good to great.

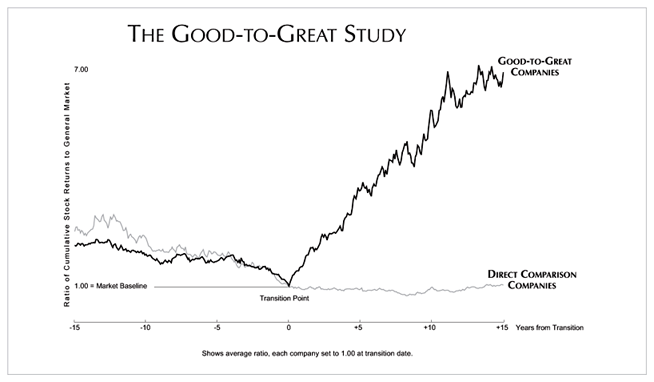

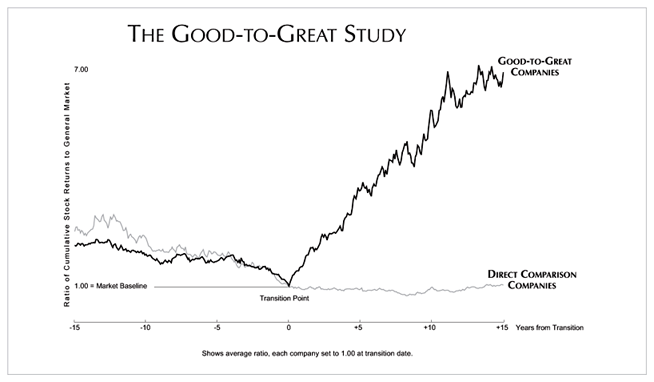

To quickly grasp the concept of the project, look at the chart on page 2. In essence, we identified companies that made the leap from good results to great results and sustained those results for at least fifteen years. We compared these companies to a carefully selected control group of comparison companies that failed to make the leap, or if they did, failed to sustain it. We then compared the good-to-great companies to the comparison companies to discover the essential and distinguishing factors at work.

The good-to-great examples that made the final cut into the study attained extraordinary results, averaging cumulative stock returns 6.9 times the general market in the fifteen years following their transition points.

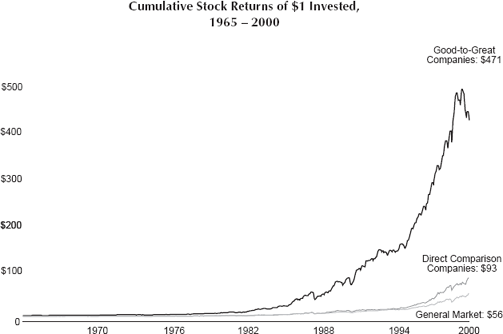

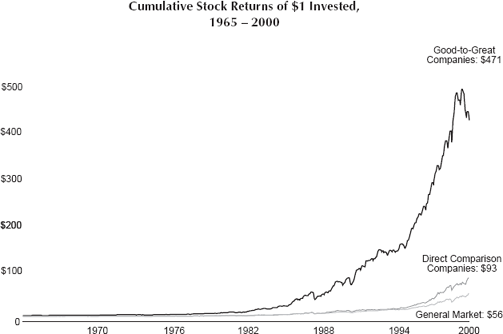

These are remarkable numbers, made all the more remarkable when you consider the fact that they came from companies that had previously been so utterly unremarkable. Consider just one case, Walgreens. For over forty years, Walgreens had bumped along as a very average company, more or less tracking the general market. Then in 1975, seemingly out of nowherebang!Walgreens began to climb... and climb...and climb... and climb... and it just kept climbing. From December 31, 1975, to January 1, 2000, $1 invested in Walgreens beat $1 invested in technology superstar Intel by nearly two times, General Electric by nearly five times, Coca-Cola by nearly eight times, and the general stock market (including the NASDAQ stock run-up at the end of 1999) by over fifteen times.

Notes:

1. $1 divided evenly across companies in each set, January 1, 1965.

2. Each company held at market rate of return, until transition date.

3. Cumulative value of each fund shown as of January 1, 2000.

4. Dividends reinvested, adjusted for all stock splits.

How on earth did a company with such a long history of being nothing special transform itself into an enterprise that outperformed some of the best-led organizations in the world? And why was Walgreens able to make the leap when other companies in the same industry with the same opportunities and similar resources, such as Eckerd, did not make the leap? This single case captures the essence of our quest.

This book is not about Walgreens per se, or any of the specific companies we studied. It is about the questionCan a good company become a great company and, if so, how?and our search for timeless, universal answers that can be applied by any organization.