Why Business Thinking Is Not the Answer

We must reject the ideawell-intentioned, but dead wrongthat the primary path to greatness in the social sectors is to become more like a business. Most businesseslike most of anything else in lifefall somewhere between mediocre and good. Few are great. When you compare great companies with good ones, many widely practiced business norms turn out to correlate with mediocrity, not greatness. So, then, why would we want to import the practices of mediocrity into the social sectors?

I shared this perspective with a gathering of business CEOs, and offended nearly everyone in the room. A hand shot up from David Weekley, one of the more thoughtful CEOsa man who built a very successful company and who now spends nearly half his time working with the social sectors. Do you have evidence to support your point? he demanded. In my work with nonprofits, I find that theyre in desperate need of greater disciplinedisciplined planning, disciplined people, disciplined governance, disciplined allocation of resources.

What makes you think thats a business concept? I replied. Most businesses also have a desperate need for greater discipline. Mediocre companies rarely display the relentless culture of disciplinedisciplined people who engage in disciplined thought and who take disciplined actionthat we find in truly great companies. A culture of discipline is not a principle of business; it is a principle of greatness.

Later, at dinner, we continued our debate, and I asked Weekley: If you had taken a different path in life and become, say, a church leader, a university president, a nonprofit leader, a hospital CEO, or a school superintendent, would you have been any less disciplined in your approach? Would you have been less likely to practice enlightened leadership, or put less energy into getting the right people on the bus, or been less demanding of results? Weekley considered the question for a long moment. No, I suspect not.

Thats when it dawned on me: we need a new language. The critical distinction is not between business and social, but between great and good. We need to reject the nave imposition of the language of business on the social sectors, and instead jointly embrace a language of greatness.

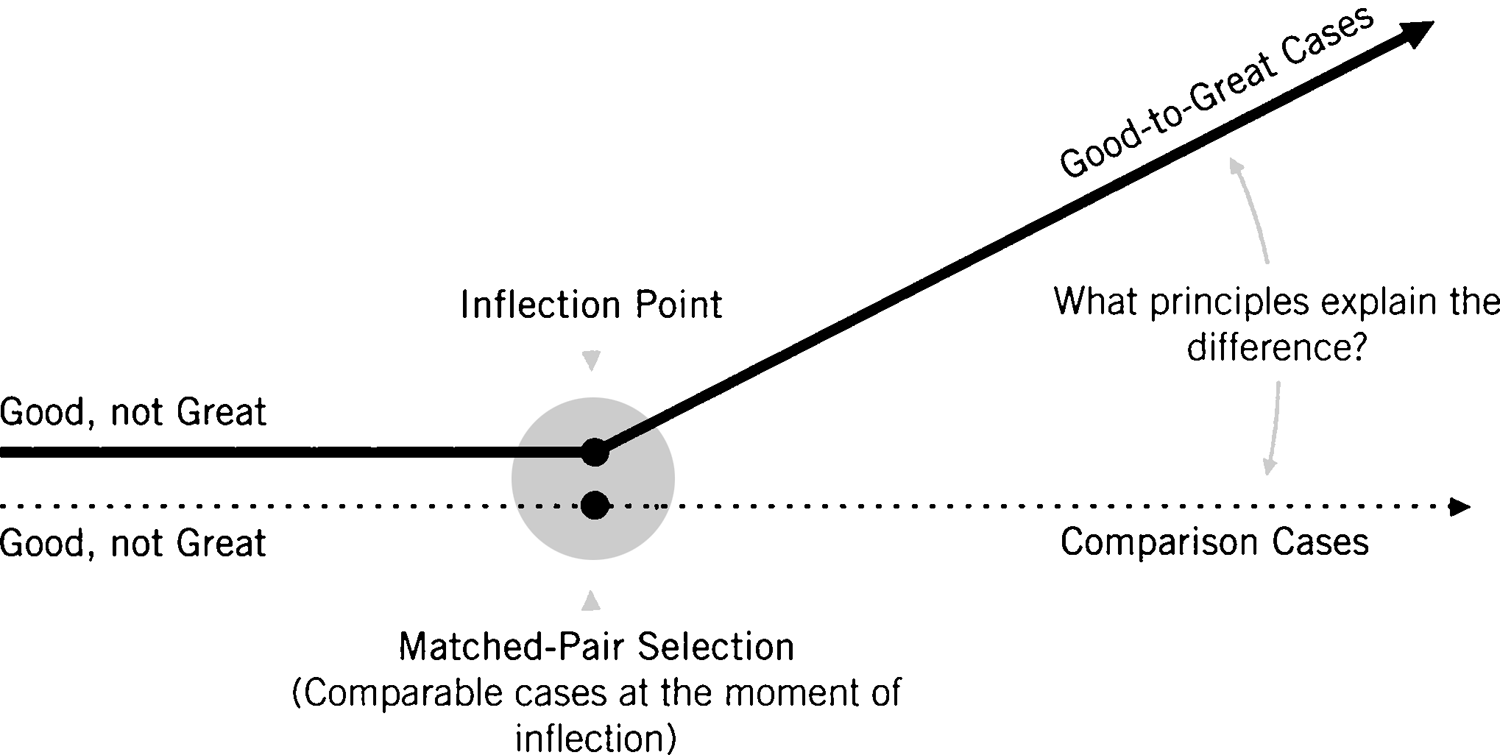

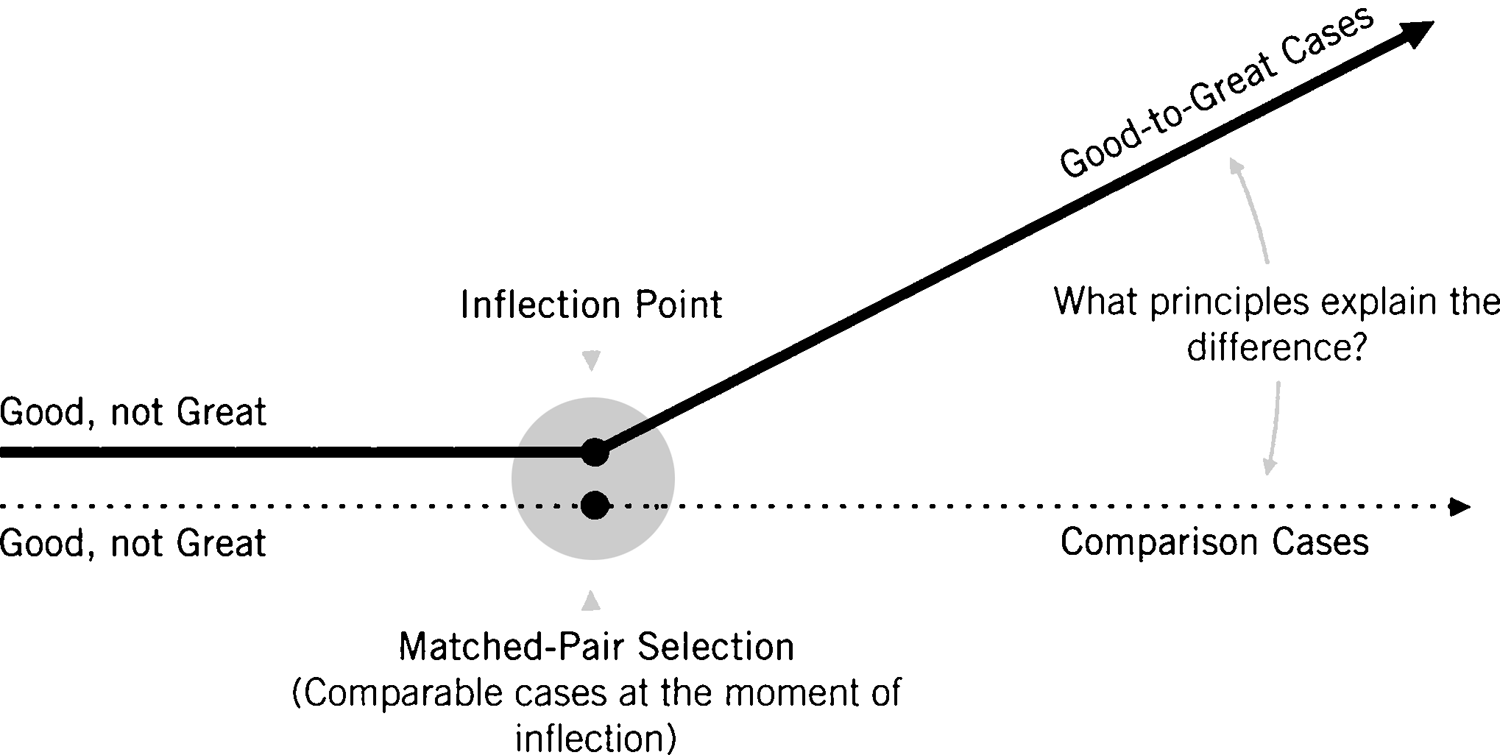

Thats what our work is about: building a framework of greatness, articulating timeless principles that explain why some become great and others do not. We derived these principles from a rigorous matched-pair research method, comparing companies that became great with companies that did not. Our work is not fundamentally about business; it is about what separates great from good.

THE GOOD-TO-GREAT MATCHED-PAIR RESEARCH METHOD

Social sector leaders have embraced this distinctionthe principles of greatness, as distinct from the practices of businesswith remarkable ease. If a nonbusiness reader is just as likely to email me as a business reader, then somewhere between 30% and 50% of those who have read Good to Great come from nonbusiness. Weve received thousands of calls, letters, emails and invitations from education, healthcare, churches, the arts, social services, cause-driven nonprofits, police, government agencies, and even military units.

Two messages leap out. First, the good-to-great principles do indeed apply to the social sectors, perhaps even better than we expected. Second, particular questions crop up repeatedly from social sector leaders facing realities they perceive to be quite different from the business sector. Ive synthesized these questions into five issues that form the framework of this piece:

1 - Defining GreatCalibrating Success without Business Metrics

2 - Level 5 LeadershipGetting Things Done within a Diffuse Power Structure

3 - First WhoGetting the Right People on the Bus within Social Sector Constraints

4 - The Hedgehog ConceptRethinking the Economic Engine without a Profit Motive

5 - Turning the FlywheelBuilding Momentum by Building the Brand

Ive based this piece on critical feedback, structured interviews, and laboratory work with more than 100 social sector leaders. While I hope to eventually see the results of matched-pair research that uses nonbusiness entities as the data set, such research studiesdone rightrequire up to a decade to complete. In the meantime, I feel a responsibility to respond to the questions raised by those who seek to apply the good-to-great principles today, and I offer this monograph as a small interim step.

ISSUE ONE: DEFINING GREATCALIBRATING SUCCESS WITHOUT BUSINESS METRICS

In 1995, officers at the New York City Police Department (NYPD) found an anonymous note posted on the bulletin board. Were not report takers, the note proclaimed. Were the police. The note testified to the psychological shift when then Police Commissioner William J. Bratton inverted the focus from inputs to outputs. Prior to Bratton, the NYPD assessed itself primarily on input variablessuch as arrests made, reports taken, cases closed, budgets metrather than on the output variable of reducing crime. Bratton set audacious output goals, such as attaining double-digit annual declines in felony crime rates, and implemented a catalytic mechanism called Compstat (short for computer comparison statistics).

A 1996 Time article describes a police captain sweating at a podium in the command center. He stands before an overhead map with a bunch of red dots, showing a significant increase in robberies in his precinct. In a Socratic grilling session reminiscent of Professor Kingfield in The Paper Chase, the questions come relentlessly. What is the pattern here? What are you going to do to take these guys out?

This distinction between inputs and outputs is fundamental, yet frequently missed. I recently opened the pages of a business magazine that rated charities based in part on the percentage of budget spent on management, overhead and fundraising. Its a well-intentioned idea, but reflects profound confusion between inputs and outputs. Think about it this way: If you rank collegiate athletic departments based on coaching salaries, youd find that Stanford University has a higher coaching cost structure as a percentage of total expenses than some other Division I schools. Should we therefore rank Stanford as less great"? Following the logic of the business magazine, thats what we might concludeand our To say, Stanford is a less great program because it has a higher salary structure than some other schools would miss the main point that Stanford Athletics delivered exceptional performance, defined by the bottom-line outputs of athletic and academic achievement.

The confusion between inputs and outputs stems from one of the primary differences between business and the social sectors. In business, money is both an input (a resource for achieving greatness) and an output (a measure of greatness). In the social sectors, money is only an input, and not a measure of greatness.

A great organization is one that delivers superior performance and makes a distinctive impact over a long period of time. For a business, financial returns are a perfectly legitimate measure of performance. For a social sector organization, however, performance must be assessed relative to mission, not financial returns. In the social sectors, the critical question is not How much money do we make per dollar of invested capital? but How effectively do we deliver on our mission and make a distinctive impact, relative to our resources?