BUILT

TO

LAST

Successful Habits

of Visionary Companies

James C. Collins

Jerry I. Porras

To Joanne and Charlene

Contents

O n March 14, 1994, we shipped the final manuscript for Built to Last to our publisher. Like all authors, we had hopes and dreams for the book, but never dared allow these hopes to become predictions. We knew that for every successful book, ten or twenty equally good (or better) works languish in obscurity. Two years later, as we write this introduction to the paperback edition, we find ourselves somewhat astonished by the success of the book: more than forty printings worldwide, translation into thirteen languages, and best-seller status in North America, Japan, South America, and parts of Europe.

There are many ways to measure the success of a book, but for us the quality of our readership stands at the top of the list. Fueled initially by favorable coverage in a wide range of magazines and journals, the book quickly found an audience and ignited a word-of-mouth chain reaction among thoughtful readers. And that is a key word: readers. What is the true price of a book? Not the fifteen- to twenty-five-dollar cover price. For a busy person, the cover price pales in comparison to the hours required to read and digest a book, especially a research-based, idea-driven work like ours. Most people dont read the books they buy, or at least not all of them. Weve been pleasantly surprised not only by how many people have bought the book, but by how many have actually read it. From CEOs and senior executives to aspiring entrepreneurs, leaders of nonprofits, investors, journalists, and managers early in their careers, busy people have invested in Built to Last with their most precious resourcetime.

We attribute this widespread readership to four primary factors. First, people feel inspired by the very notion of building an enduring, great company. Weve met executives from all over the world who aspire to create something bigger and more lasting than themselvesan ongoing institution rooted in a set of timeless core values, that exists for a purpose beyond just making money, and that stands the test of time by virtue of the ability to continually renew itself from within.

Weve seen this motivation not only in those who shoulder the responsibility of stewardship in large organizations, but alsoand perhaps especiallyin entrepreneurs and leaders of small to midsized companies. The examples set by people like David Packard, George Merck, Walt Disney, Masaru Ibuka, Paul Galvin, and William McKnightthe Thomas Jeffersons and James Madisons of the business worldset a high standard of values and performance that many feel compelled to try to live up to. Packard and his peers did not begin as corporate giants; they began as entrepreneurs and small business people. From there they built small, cash-strapped enterprises into some of the worlds most enduring and successful corporations. One executive of a small entrepreneurial company said, To know that they did it gave us confidence and a model to follow.

Second, thoughtful people crave time-tested fundamentals; theyre tired of the fad of the year boom-and-bust cycle of management thinking. Yes, the world changesand continues to change at an accelerated pacebut that does not mean that we should abandon the quest for fundamental concepts that stand the test of time. On the contrary, we need them more than ever! Certainly, we always need to search for new ideas and solutionsinvention and discovery move humankind forwardbut the biggest problems facing organizations today stem not from a dearth of new management ideas (were inundated with them), but primarily from a lack of understanding the basic fundamentals and, most problematic, a failure to consistently apply those fundamentals. Most executives would contribute far more to their organizations by going back to basics rather than flitting off on yet another short-lived love affair with the next attractive, well-packaged management fad.

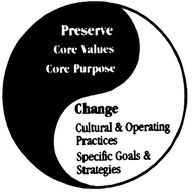

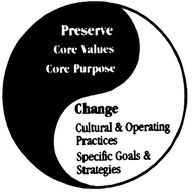

Third, executives at companies in transition find the concepts in Built to Last to be helpful in bringing about productive change without destroying the bedrock foundation of a great company (or, in some cases, building that bedrock for the first time). Contrary to popular wisdom, the proper first response to a changing world is not to ask, How should we change? but rather to ask, What do we stand for and why do we exist? This should never change. And then feel free to change everything else. Put another way, visionary companies distinguish their timeless core values and enduring purpose (which should never change) from their operating practices and business strategies (which should be changing constantly in response to a changing world). This distinction has proven to be profoundly useful to organizations amid dramatic transformationdefense companies like Rockwell facing the end of the Cold War, utilities like the Southern Company facing accelerating deregulation, tobacco companies like UST facing an increasingly hostile world, family companies like Cargill facing the first generation of nonfamily leadership, and companies with visionary founders like Advanced Micro Devices and Microsoft facing the need to transcend dependence on the founder.

Figure I.A

Continuity and Change in Visionary Companies

Even the visionary companies studied in Built to Last need to continually remind themselves of the crucial distinction between core and noncore, between what should never change and what should be open for change, between what is truly sacred and what is not. Hewlett-Packard executives, for example, speak frequently about this crucial distinction, helping HP people see that change in operating practices, cultural norms, and business strategies does not mean losing the spirit of the HP Way. Comparing the company to a gyroscope, HPs 1995 annual report emphasizes this key idea: Gyroscopes have been used for almost a century to guide ships, airplanes, and satellites. A gyroscope does this by combining the stability of an inner wheel with the free movement of a pivoting frame. In an analogous way, HPs enduring character guides the company as we both lead and adapt to the evolution of technology and markets. Johnson & Johnson used the concept to challenge its entire organization structure and revamp its processes while preserving the core ideals embodied in the Credo. 3M sold off entire chunks of its company that offered little opportunity for innovationa dramatic move that surprised the business pressin order to refocus on its enduring purpose of solving unsolved problems innovatively. Indeed, if there is any one secret to an enduring great company, it is the ability to manage continuity and changea discipline that must be consciously practiced, even by the most visionary of companies.

Fourth, there are many visionary companies out there, and theyve found the book to be a welcome confirmation of their approach to business. The companies in our study represent only a small slice of the visionary company landscape. Visionary companies come in many packages: large and small, public and private, high profile and reclusive, stand-alone companies and subsidiaries. Well-known companies not in our original study such as Coca-Cola, L.L. Bean, Levi Strauss, McDonalds, McKinsey, and State Farm almost certainly qualify as visionary companies, and others like Nikenot yet old enoughwill probably enter that league. But there are also a large number of less well-known visionary companies, many of them private and somewhat reclusive. Some are older, well-established companies, such as Cargill, Edward D. Jones, Fannie Mae, Granite Rock, Molex, and Telecare. Others are up-and-coming companies, such as Bonneville International, Cypress, GSD&M, Landmark Communications, Manco, MBNA, Taylor Corporation, Sunrise Medical, and WL Gore. The business press tends to rivet our attention on the Icarus companieshigh-profile firms either on the way up or the way down. We regularly come in contact with a very different group of companiessolid, paying attention to the fundamentals, shunning the limelight, creating jobs, generating wealth, and making a contribution to society. We feel optimistic as we see these companiesand there are a lot of themmake their way in the world.

Next page