BY THE SAME AUTHOR

Justice Denied: The Law versus Donald Marshall

Unholy Orders: Tragedy at Mount Cashel

Rare Ambition: The Crosbies of Newfoundland

The Prodigal Husband: The Tragedy of Helmuth and Hanna Buxbaum

The Judas Kiss: The Undercover Life of Patrick Kelly

Copyright 1998, 1999 by Michael Harris

Cloth edition published 1998

Updated trade paperback edition published 1999

All rights reserved. The use of any part of this publication reproduced, transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, or stored in a retrieval system, without the prior written consent of the publisher or, in the case of photocopying or other reprographic copying, a licence from the Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency is an infringement of the copyright law.

Canadian Cataloguing in Publication Data

Harris, Michael, 1948

Lament for an ocean : the collapse of the Atlantic cod fishery : a true crime story

eISBN: 978-1-55199-476-5

1. Cod fisheries Atlantic Coast (Canada). 2. Cod fisheries Economic aspects Newfoundland. 3. Fishery policy Canada. 4. Fishery policy Newfoundland. I. Title. II. Title: Collapse of the Atlantic cod fishery.

SH351.C5H375 1999 338.37276330916344 C99-931849-7

We acknowledge the financial support of the Government of Canada through the Book Publishing Industry Development Program for our publishing activities. Canada

We further acknowledge the support of the Canada Council for the Arts and the Ontario Arts Council for our publishing program.

McClelland & Stewart Inc.

The Canadian Publishers

75 Sherbourne Street,

Toronto, Ontario

M5A 2P9

v3.1

For my grandfather William Tilley, 18941968,

who left Newfoundland in the Great Depression, never to return.

On his deathbed, he asked for partridge berries.

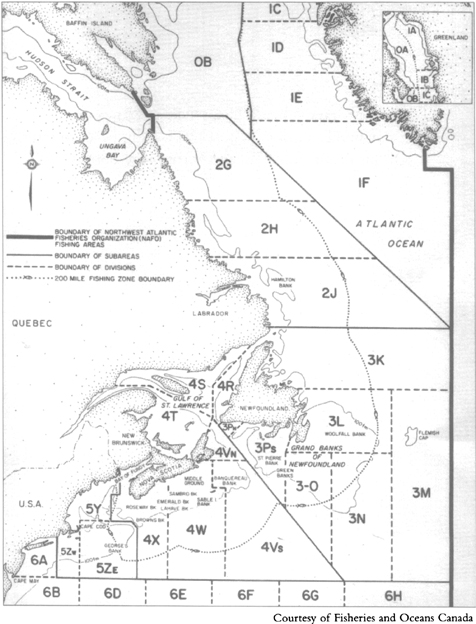

Two-Hundred-Mile Fishing Zone and NAFO Fishing Boundaries

Contents

What we have is not an adjustment problem, but the most wrenching societal upheaval since the Great Depression. Our communities are in crisis. The people of the fishery are in turmoil.

Earle McCurdy, president of the Fish, Food, and Allied Workers union, in Atlantic Fisherman

If I were an Atlantic premier, Id sue the feds. If I were a fisherman or a processor, Id launch a class-action lawsuit. Heads should be rolling in Ottawa.

Silver Donald Cameron, The Globe and Mail

1

NOBODYS WATERS

I t was the other shot that was heard around the world. The 50-calibre machine-gun bursts from the Cape Roger, three in all, marked the first time since Confederation that Canada had fired on another country in defence of the national interest. When the order came to open fire, the officers aboard the fisheries patrol vessel were so taken aback, they asked that the command be repeated. The fateful words crackled once more over the ships radio: an initial burst was to be fired over the bow of the Spanish trawler Estai, the next rounds into her crew sixty seconds later if she refused to stop. After warning the Spanish captain to move his crew forward, Captain Newman Riggs nodded to Bernie Masters, who adjusted the sights on the Cape Rogers heavy gun and sucked in a deep breath as his finger squeezed the trigger.

This act of war, as it would soon be called, was perpetrated against an unarmed fishing vessel by the nation that had invented peacekeeping, in the name of conserving a fish most Canadians had never heard of, and until very recently, most fishermen treated as an unwanted by-catch: the suddenly controversial turbot.

For four nerve-wracking hours in the afternoon of March 9, 1995, the Estai had done its best to elude three Canadian patrol vessels, two from the Department of Fisheries and Oceans ( DFO ), the other from the Canadian Coast Guard. The ships had been pursuing the Estai for suspected illegal turbot fishing off Newfoundlands Grand Banks. There were even allegations that the vessel had a secret hold containing twenty-five tonnes of contraband American plaice. In an attempt to outrun its pursuers, Captain Enrique Davila Gonzlez had ordered his men to cut the Estais nets, worth $80,000. Anything was better than having the contents of the Estais hold, bulging with undersized fish, revealed.

Canada had been preparing for this moment for several weeks. The federal fisheries minister, Brian Tobin, first raised the prospect of using force to end chronic overfishing off Canadas east coast in a full cabinet meeting. Prime Minister Jean Chrtien had agreed to the discussion and must have been surprised that Tobins idea hadnt died a quick death around the cabinet table. What the prime minister didnt know was that his enterprising fisheries minister had already successfully lobbied his colleagues, some of whom had rejected their own departmental advice to side with Tobin.

The Justice Department recommended against seizing foreign fishing vessels in international waters because the relevant law was either muddy, non-existent, or favoured the Spanish; the RCMP opposed the use of force because of civil liabilities it feared might arise out of an armed confrontation; the Department of National Defence rejected Tobins gunboat diplomacy against a NATO ally.

But opposition from the mandarins didnt stop Justice Minister Allan Rock, Solicitor-General Herb Grey, or Defence Minister David Collenette from backing Tobin. After the cabinet meeting that laid the groundwork for confronting the Spanish on the high seas, a grudgingly impressed prime minister buttonholed his fisheries minister to compliment him on his private manoeuvring. There was no such praise, grudging or otherwise, from Foreign Affairs Minister Andr Ouellet. From start to finish in what would become known as the Turbot War, he and his department remained bitterly opposed to raising a fist to a friend over something as inconsequential as fish stocks.

The crew of the Estai was on tenterhooks as the Canadian vessels closed in. The prospect of a catastrophic collision in the dense fog and rough, icy seas of the northwest Atlantic was bad enough, but the 50-calibre bursts had taken the sea chase to an unacceptable level of risk. Just before 5:00 p.m. Ottawa time, Gonzlez put a stop to the dangerous game of cat and mouse hed been playing with the three Canadian ships. When the Estai finally gave up, a team of armed Canadian fisheries officers in orange survival suits, led by Frank Snelgrove, scrambled aboard, seized the ship, and placed her captain under arrest.

The Spanish crew had fended off two previous boarding attempts. Earlier on that raw March day the RCMP had tried to board the Estai using hooks and ladders. The crew had repulsed them by uncoupling their grappling gear. It was a bad moment for the Mounties. They might always get their man, but not necessarily their fisherman. When they tried to get back into their Zodiac, it capsized, sending the boarding party into the ocean and their Uzi submachine guns to the bottom. Ultimately, it took seven DFO officers to do what the RCMP could not.