Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

In memory of Willard A. Lockwood, editor, mentor, and friend

All the key people and places appearing in this account are real. However, a few minor characters and adventures are composites, respectively, of several people or events. Additionally, some names of secondary characters have been changed, and the chronology has been shifted slightly. These modifications are minor in scope.

The fishing comes and the fishing goes

Nothing stays the same

Way up here on this northern coast

Its just a waiting game

Now when things are slow

Its a comfort just to know

Harbor lights are shining

To light my way back home

Harbor lights are shining

In the town I call my own

FRANK GOTWALS, HARBOR LIGHTS

Thomas Wolfe famously said, You cant go home again. Wolfe, a New Englander by education if not by birth, visited Maine at least once. Still, he was probably as adamant about the unrepeatable nature of the lobster coast as he was about his home turf in North Carolina. Childhood memories of a revered place, so the logic goes, can never be repeated.

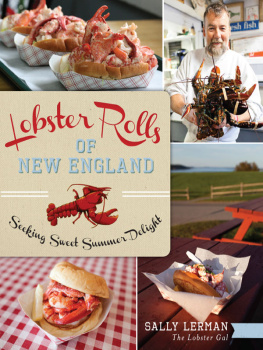

Yet, I discovered recently, this maxim is not always so. There are destinations in Maine where lobstermen still bake blueberry pies derived from wild, low-bush blueberries. Home is where the kitchen is. From my boyhood summering in Maine, I remember this small fruit, tart and sweeter than the larger, cultivated blueberries found in supermarkets. Local cooks are adamant about the tiny berries. Domesticated high-bush varieties would never do, at least not in a Maine kitchen.

Traditional cuisine does not end there. For lunchwhile the blueberry pie is coolinglobster pot pie (with local celery and potatoes) will be created from scratch, all fresh. The succulent lobster itself has been hauled moments ago from the crystal clear Gulf of Maine. Most of a lobstermans produce comes directly from field or sea. Harvests from each are courtesy of sun and clean water.

My memories return in waves.

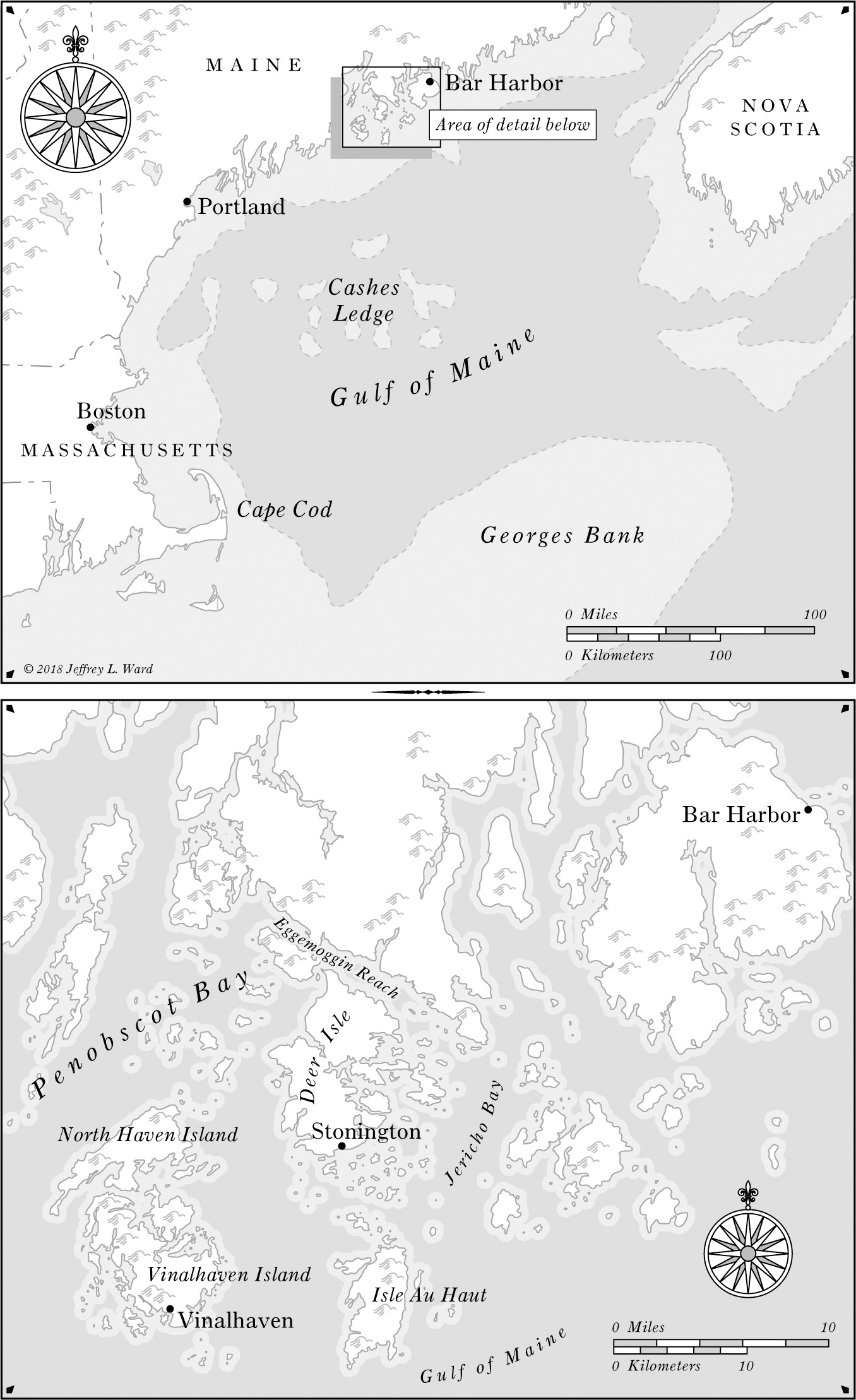

Even more than local recipes, I remember the rocky seascapes, still unblemished. I recall cozy harbors with white lobster boats and brightly colored buoys bobbing in the surf. Though fewer, these lobstering coves are still busy, jumping with life. I can smell the mudflats at low tide, rich and rank, an acquired taste that opens up my lungs and even now, from a distance, makes me smile.

Mostly, I remember the people, the faces, the voices, that populate the remote villages where lobstering is a way of life. Rugged crags and rugged faces: The landscape matches the cut of ones jib. The tight-knit communities turn out en masse for a boat launching, a funeral, a fire. Every captain responds to a boat in distress. This way of life persists.

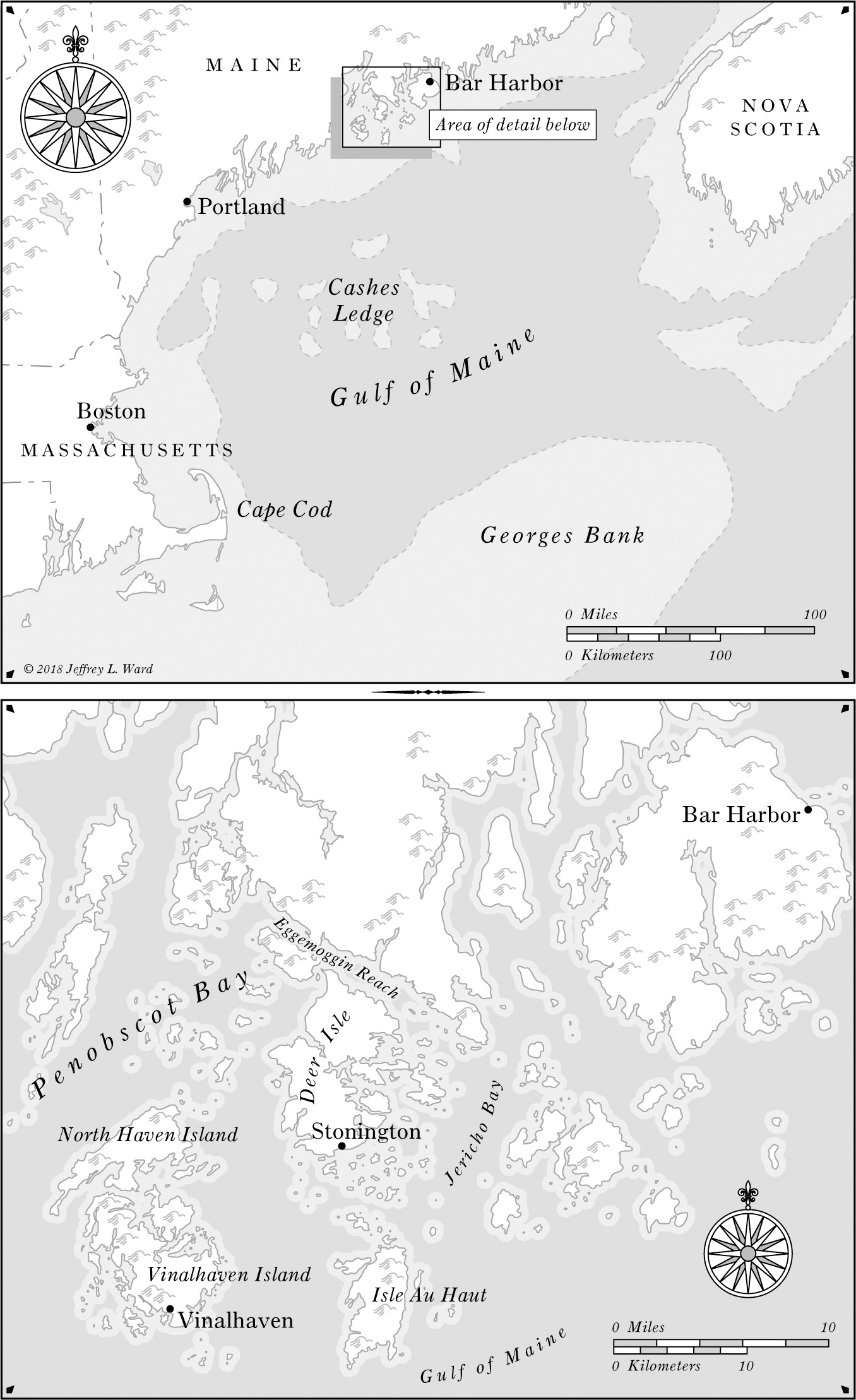

Four years ago, I began my search for the most authentic lobster villages in Maine, places where communities, fishermen, and native cuisine still thrive. A recent glut of lobster and a concomitant drop in prices were putting a squeeze on lobstermen. The Maine lobster culture was threatened. But there was time, I thought, to capture the essence of the lobster coast before it all changed forever.

If any breed could respond and adapt, I figured it would be the seasoned lobstermen in those distant villages. The colorful residents and their fathers and grandfathers had seen booms and busts before. The knowledge of how to survive with versatility had been passed down from generation to generation. To document that legendary resilience was my motivation for crossing half the continent to explore the Maine coast again. I came from the Chesapeake Bay by way of the Rocky Mountains.

Recently, I had spent two years living on Tilghman Island, home of the Chesapeakes famed skipjack fleet, witnessing the crash of another fishery. The Chesapeake watermen were suffering the impacts of overfishing, the scourge of fishermen around the world. But in Maine, the problem was not overharvesting, but, rather, too many lobsters. The challenges were opposite in cause and effect. The biggest mystery was how the glut had come into being. In 2012 and 2013, the market was flooded with lobsters. Prices were at rock bottom. Lobstermen were having trouble selling their catch. However, upon my arrival in 2014, the bottleneck was starting to relax. Catches were still astronomicalsix times normalbut the distribution pipeline was unclogged. It was looking like a win-win situation: abundant lobster for everyone. But a boom, the lobstermen reminded me, was a bittersweet gift. Prices could plummet more. Still, after my tenure aboard the last sailing skipjacks, I was ready for some good news, however fleeting it might be.

If I could just solve the puzzle of the booms origins and impacts, I thought, and perhaps watch the lobstermen bounce back, my odyssey would be complete.

Now back to that lobster pie. More recollections come in with the tide. I recall eating the crust with my fingers. I remember such down-home pleasures from my teenage summers in Maine. Thanks to my table manners, I was considered from away, or in the parlance of more diplomatic local residents, I was summer folk. I realize now that I had not fully enjoyed a pure Maine experience in the 1970s because I was trespassing. The natives were the lobstermen and I was the interloper. With thousands of onlookers venturing to the Maine coast each summer, the local culture has morphed into a hybrid of sorts: no longer 100 percent authentic. Many lobster villages are now vacation towns, too. Sure, some lobstermen run boardinghouses or boat tours, but the locals are uncomfortable serving two mastersthe seafood industry and tourism. This mix comprises a web of modernization. Lobstermen have learned to tolerate, if not accept, the experiment.

Despite some of the coast being overrun, I had heard rumors that a few idyllic villages remained. They are not in any tourist guide. Here, the local residents do not need our business. They are doing finefor now. Lobstering has come on like a summer downpour. American lobster, which is by far the largest fishery in Maine, had a nationwide harvest value of $460 million in 2013. Out of 149 million pounds caught nationally, more than 127 million pounds (an all-time record), or 85 percent, were landed in Maine. Thirty years ago, the catch was one-sixth that level (only 21 million pounds), and Maine fishermen were suffering. There was talk of overharvesting. Not so today. All talk is about the boom.

The bonanza brought stunning profits to lobstermen and their communities. Older men landed $200,000 or more for the first time in their lives; teenagers made $60,000 in a summer. Young and old fishermen alike bought new trucks and new and bigger boats. They took out larger mortgages and moved into spacious homes. Banks gave away loans like free beer at a picnic. Businesses expanded. Unlike the Midwests white working class, which has lost touch with the American dream, Maine lobstermen now had money in the bank and were earning their way into the middle class. Locals became dependent on the riches of the sea.