Copyright 2018 by Sean Deveney

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

Skyhorse Publishing books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or .

Skyhorse and Skyhorse Publishing is are registered trademarks of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc., a Delaware corporation.

Visit our website at www.skyhorsepublishing.com.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file.

Cover design by Tom Lau

Cover photos courtesy of Associated Press

All photos in insert courtesy of Associated Press

Print ISBN: 978-1-5107-3063-2

Ebook ISBN: 978-1-5107-3064-9

Printed in the United States of America

CONTENTS

Preface

I N 2012, A STUDY BY Northwestern Medicine appeared to support a neurological theory about the inconsistencies of memory. The authors of the study compared the brains ability to remember specific events to the playing of a game of telephone, where one participant whispers a sentence to the next participant until, by the time the game is over, the sentence becomes twisted and unrecognizable. Your memories, the theory went, undergo some twist each time they are recalled, and the twists add up until you remember something falsely altogether. For example, a 2003 study showed that 73 percent of 569 college students polled about 9/11 said they remembered watching the first plane fly into the north tower of the World Trade Center on the day itself, almost as it happened. But that footage did not reach news desks until the following day. Only two years after the tragedy, their brains had reordered things, tricked them into remembering something that hadnt happened.

For any one of us, an individual memory of an event changes over time in the same way. Each time the brain recalls the memory, some detail, minuscule perhaps, is omitted or added or changed. When the memory comes back again, the change is still there, only this time, some additional detail may be altered, too, which is then included in the next recollection of the memory. The more the human brain returns to a memory, then, the more alterations it makes and the less accurate it becomes as the modifications are absorbed. Just as the sentence gets more mangled as the number of participants in the game of telephone increases, the more times the human brain returns to a specific memory, the more mangled that memory gets over time. The consequence of this can be jarring: The more you remember something, the more you are forgetting it.

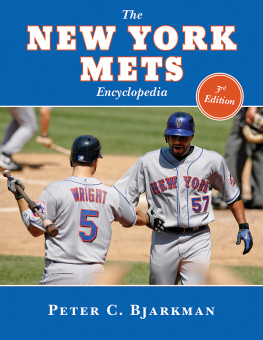

This was a useful lesson to keep in mind as I was researching and conducting interviews into this book, and struck me especially when considering the varying accounts of the 1986 World Series, won by the Mets over the Red Sox, put out by members of the losing side over the years. I spent much of my free time with three-decades-old periodicals and books, trying to dig into the contemporaneous documentation of the era (with help from the patience of my partner, Carrie Russell, and our newborn daughter, Maisie) to better understand what the mood was as major events were unfolding. That sort of dry and straightforward documentation, of course, serves as the framework of any reconstruction of a particular place and timein this case, New York in the middle of the decade, when the city and the 1980s were at their height. It is through that methodical research that the foundation of the story emerges, without the vagaries of memories that have been yellowed and distorted by the passage of years.

But what stands out from the research into this project is the details, the small things that are indelibly etched into the memoriesneurology be damnedof people who lived and worked in New York, and were at the center of the events described here. Journalist Margot Roosevelt, then known as Margot Hornblower and covering New York for the Washington Post, had trouble recalling some of the specific stories shed written at the time. But she remembered vividly some details, memories shed not tapped into in a long time, like when powerful city lawyer Roy Cohn answered the door to his office townhouse at Saxe, Bacon and Bolan wearing nothing but a thin blue robe, obviously naked underneath, or the snide and contemptuous letter shed received from Ed Koch days after having interviewed the mayor in 1987. I sat across a conference table from Michael Chertoff, who was a thirty-two-year-old assistant US attorney in Rudy Giulianis Southern District of New York office before, twenty years later, becoming the Secretary of the Department of Homeland Security. In 1986, Chertoff had conducted the biggest Mafia-busting prosecution in the nations history, just the beginning of an illustrious career. But what stood out from our conversation was the way his face broke into a smile when he remembered his mentors, US Circuit Court judge Murray Gurfein and prosecutor Barbara Jordan, and the excitement he still conjured up when he told me the story of the New York police finding a palm print in a carat his suggestionthat helped lock in his prosecution of the murder of Carmine Galante.

Giants star linebacker Harry Carson, who helped the team to its first championship of the modern era, has a photo to solidify one of his most vivid memories, of him at midfield at the Rose Bowl in Pasadena, alone for the coin toss and standing across from five Broncos captains just ahead of Super Bowl XXI. But again, its the little things he remembers that stand out to the interviewer, like his affinity for cheap-steak chain restaurant Beefsteak Charlies, where he liked to hang out while teammates frequented bars and clubs. Likewise, former Brooklyn prosecutor Ed McDonald has been involved in some of the most high-profile cases around New Yorks underworldhe handled Mafia informant and Goodfellas subject Henry Hillbut his low-voiced impersonation of foul-mouthed former Brooklyn Democratic boss Meade Esposito, whom he convicted in 1987, is uncanny and funny, the kind of detail that cant be culled from magazines or newspapers. Neurologists are surely right to say memories can be frayed with time and use, and that some element of truth is stripped away as memories are revisited. But for an interviewer and researcher, there is nothing quite as satisfying as one of those intensely remembered details, one kernel of truth that emerges from the rubble and sheds a different light on the narrative, one bit of proof that memory does matter.

..

From a distance of decades, what we think of as the high-living 1980s encapsulates only about five years or so, and centers on one place: New York City. The economic boom that followed the fiscal crisis of the mid-1970s, when the city had to be rescued from bankruptcy, did not kick in until late 1982, after the stock market dove to a low of 776 points and new federal orders on deregulation under president Ronald Reagan took hold. That boom can be traced alongside the success of the market, to a high of 2,746 in August 1987 and ultimately, to its crash two months later, when the entire world economy deflated and the Dow Jones average lost a record 22.6 percent. In that brief time, fortunes were amassed by corporate raiders, money pumped through the financial sector of New York and propped up the city coffers, an entire class of nouveau riche New Yorkers was minted and celebrated, and greed (heretofore the third on the list of the seven deadly sins) was extolled as a virtueor, as Ivan Boesky said in a speech, greed is all right.