The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

In June 2018, I was under an umbrella at the porticone to the left of St. Peters trying to tell the Swiss Guard over the din of the downpour that I had a meeting with Pope Francis. I wasnt on their listhis private meetings seldom areso they had to call up to what is likely the worlds most famous guesthouse to make sure.

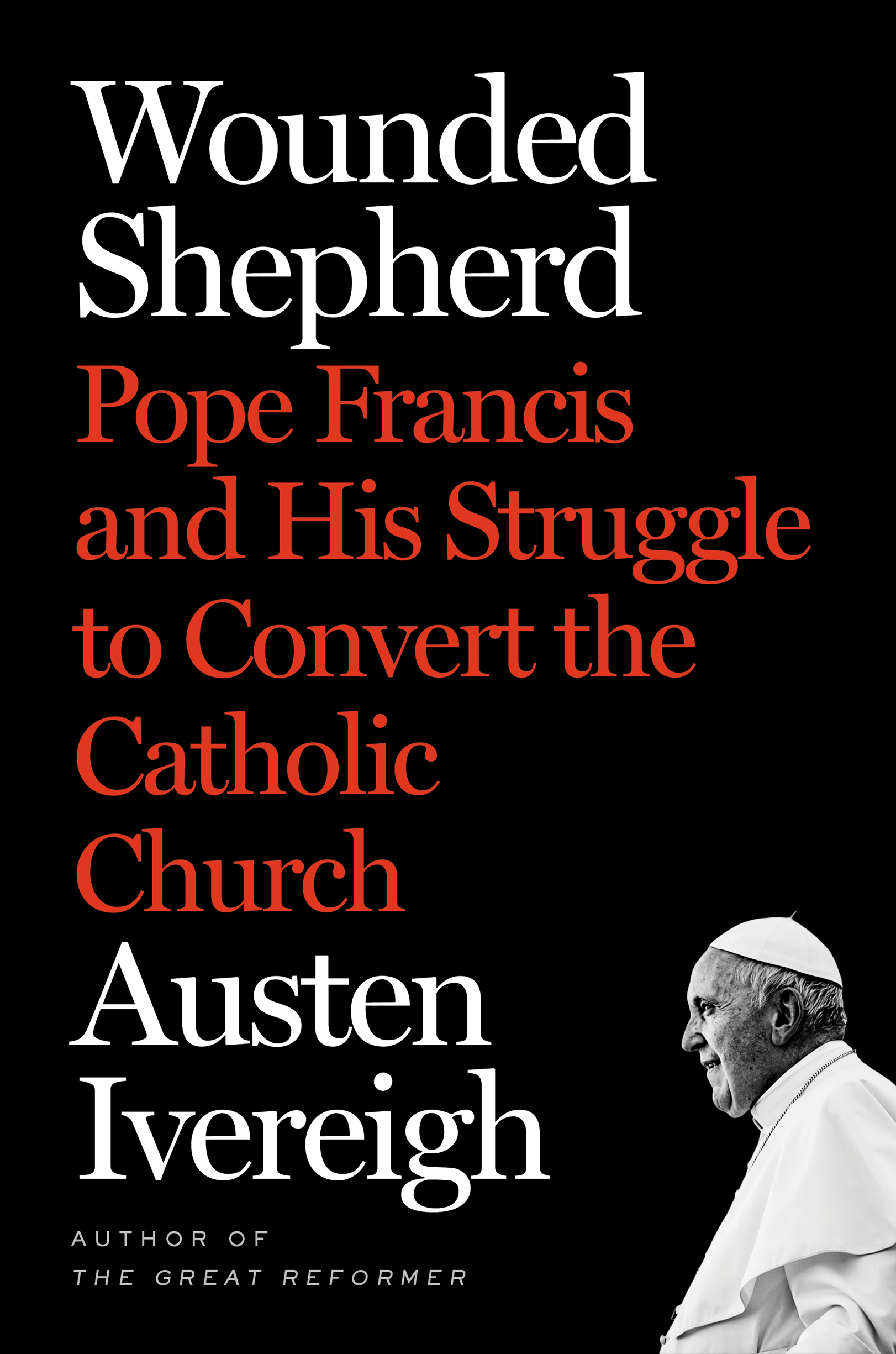

After the nod and the salute, and a ten-minute walk through the cobbled courtyards, I was at the Casa Santa Marta, an unremarkable building that from the outside could be a bank or an office. I had last met its long-term guest in November 2014, when, after Mass, I had presented him with a copy of my biography, The Great Reformer: Francis and the Making of a Radical Pope.

This time, I had a recorder in my pocket, but wasnt sure if I would use it. The book in your hands, an account of church reform over the past six years, 2013 to 2019, was already substantially written, and I bubbled with questions. But it was the pope who, via an intermediary, had asked for the meeting, in the gentlest way possible: could I perhaps find the time, when I was next in Rome?

I was shown into the visitors room on the ground floor, from where I imagined I would be taken to his three-room suite. But it was Francis himself who came in, closing the door behind him, as I stumbled awkwardly to my feet. There was no courtier to say, The Holy Father will see you now, just the pastor-in-chief taking my hand and thanking me for my kindness in taking the trouble to come and see him. His graciousness is as legendary as his serenity, simplicity, and humility, but no less surprising when you experience it for yourself.

No, no, thank you, I spluttered, and he laughed that I spoke Spanish like a porteo, someone from his home city of Buenos Aires. Then we sat down opposite each other. There was a pause, as he looked at me tenderly. Ive read a number of things youve written about me, he said, and I just have one criticism. I braced myself. After a pause, he said, smiling: Youre too kind to me. The word in Spanish was benvolo, something like indulgent. Relieved and charmed, I assured him I would be more critical in the future, and we both laughed. The pope is fun.

He was also serious. He went on to explain, as he often has to others, that no one had thought this change of diocese was a possibility, that in March 2013 he had a small suitcase and expected to be back in Buenos Aires for Easter, how he didnt come with some great plan but had been managing the best he could with what he had.

I never did get my recorder out, and didnt need to: the following forty-five minutes were unforgettable, and have invigorated what follows in these pages. But afterward it was that first exchange that stayed with me. I realized thatfor my own good, and for the sake of truthhe was warning me against the great man myth beloved of Hollywood and a certain kind of history, in which an anointed, otherworldly figure rises up to defeat overwhelming challenges with superhuman prowess.

I realize now that The Great Reformer contributed to that myth: written in the dizzying first months of his pontificate, the parallels with his lifehow he appeared at moments of crisis in the Churchoffered an irresistible narrative: cometh the hour, cometh the man. I cringe now that I even likened him to a gaucho riding out at first light.

Six years on, the time for such projections is over. We know too much about the limits of reform: paths blocked, resistance mobilized, mistakes made. No longer the great reformer of myth, he is the wounded shepherd: to be chosen by the Holy Spirit is not to be spared the trials of history. Spending time with him, I found him to be smaller, older, more vulnerable, more ordinary than in my minds eye. I was meeting the person, not the personality.

Yet heres the thing. I also met his holiness. I saw it in the pauses, when he was listening to his heart, to those prompts of the Spirit that guide him. I saw it in his serenity, his peaceful freedom. It is a paradoxical quality: self-effacing, yet powerful; something you have, but also give away (it left me feeling loved, and free). I met the pope, in short, in all his ordinary humanity, yet at the same time was captivated by the extraordinary quality of what he was open to, of what he puts at the center of his existence. And I got the point he wanted me to understand. The real center of the Church, he told journalists shortly after his election, was not the pope, but Jesus Christ.

What follows is the story of Franciss attempt to put Christ at the Churchs center. Even though it ranges widely and deeply to explain the change that Francis seeks to bring about, Wounded Shepherd is not systematic, episodic, or chronological. There are big gaps on topics such as diplomacy and ecumenism, which an official account would need to cover. Its focus, rather, is on the conversion that Francis has sought: where it comes from, what it is, and why it has triggered such turbulence. It is the story as much of his opening of the Church to the possibility of conversion as it is of the changes he has sought to bring about.

A metaphor to capture this came in a moment of inspiration to one of my Latin American interviewees as we sat talking in his house. I was with the archbishop of Arequipa in southern Peru in April 2016, the day after the release of Franciss document on marriage and family, Amoris Laetitia (The Joy of Love).

As Archbishop Javier del Ro Alba explained his understanding of the pastoral conversion to which the pope is calling the Church, I looked beyond his shoulder through the window to the spectacular snowcapped volcano of El Misti. Following my gaze he suddenly said: What the Pope is doing is like an earthquake, a tremor, which is moving and shaking things up. And in that shaking up what will fall is what has to fall, and what will rise up is a new era in the history of the Church.

The pope was at lunch with boisterous relatives in the archbishops residence in Turin. Eat, Giorgio! the old lady told him. No, no, I have to watch myself, he protested, refusing a second helping as the six cousins and their families, more than thirty people in all, roared with laughter. It was June 2015. Even before his election two years earlier, Francis had lost the lanky, tall figure he had had for decades in Buenos Aires, and now, at seventy-eight, with the sciatica pills and the pasta, and no longer being able to callejearto walk the streets as he used tohe had filled out. But not for Signora Carla. But what do you live off? she remonstrated. You eat nothing!

He is a pope of the people, for the people; but most of all, he is a pope with the people. It is what everyone, admirers and enemies alike, notices about Francis: his natural affinity with the human race, the way he turns people you wouldnt look at twice into subjects and protagonists. Some say he is a populist in an age of populists, but that is to misunderstand populism. He is not using his at-oneness with the people to create power, for he rejects that kind of power; he does not offer boundaries to protect people from perceived threats, but doors and bridges to expand their possibilities. He is captivating and energetic, but humble. He makes mistakes, and asks forgiveness. His mission is to take the Church to the people, in order to not just save the people but to save the Church.