Contents

Guide

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

For Linda

C ONTENTS

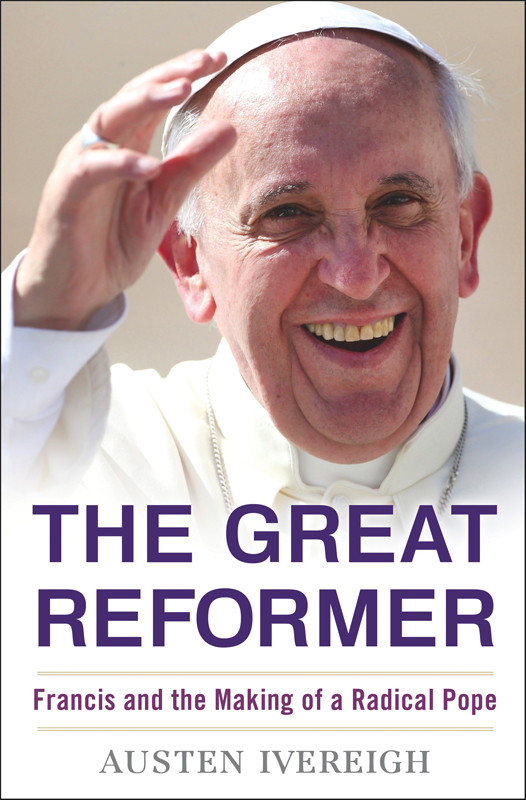

T HIS BOOK CAME out of a minutes meeting with Pope Francis in St. Peters Square in June 2013. My colleague and I had been given sought-after front-row tickets at the Wednesday audience, when there is the chance to speak to the pope as he moves along the row chatting briefly to delegates and guests. He took over two hours to reach us, because after his addressthe usual mix of homespun humor and startling metaphorshe disappeared for what seemed like an eternity among the ones he calls Gods holy faithful people. They, the anawim , the poor of God, not we, the front-row ticket holders, were his priority.

It was a sun-struck day and the exertion had taken its toll: by the time he got to us, Francis, at that point seventy-six years old, was sweating, hot, and breathless. But what most struck me was the energy he gave off: a biblical blend of serenity and playful joy. The archbishop of Canterbury, Justin Welby, put it well after he met Francis some days later. The Argentine pope, he said, is an extraordinary humanity, on fire with Christ. If joy were a flame, youd need to be made of asbestos not to get burned.

Francis had fascinated me more and more since the rainy night of his election on March 13, 2013. I was up on a TV platform overlooking St. Peters Square conducting minute-by-minute commentary for a British news channel. It had been an hour since the white smoke, and we were waiting, with the globes media, for the twitch on the balcony curtains. Some minutes before Cardinal Jean-Louis Tauran came out to announce the new pope, I had a tip-off from my old boss, the retired archbishop of Westminster, Cardinal Cormac Murphy-OConnor, who had taken part in the pre-conclave discussions but was too old to take part in the conclave itself. He told my emissary that, as it had been a short conclave, the new pope could well be Jorge Mario Bergoglio.

Bergoglio? It was a name from the past. I knew his country: it began with parakeets in hot humid rainforests, continued in vast herds of cattle and horses in great prairies between the mountains and the ocean, and ended with penguins on ice floes floating past spouting whales. It had once been a wealthy nation, one that saw itself as an outpost of Europe stranded in Latin America; later it was a textbook study in failed promise, a warning of how deep-rooted political polarities can paralyze society. I recalled a trip to Argentina in 2002 to write an article about the countrys economic collapse, when people spoke highly of their aloof and austere cardinal; but also further back, to the early 1990s, when I had lived in Buenos Aires while researching a doctoral thesis on the Church and politics in Argentine history. Over a number of visits, in the midst of attempted coups and currency crises, I had come to love that beguiling city; and living there for many months at a time, my Spanish had sprouted the inflections and idioms of porteo Spanish. It was allas W. H. Hudson titled his memoir of Argentina Far Away and Long Ago . Now Bergoglio had brought it back.

I had another memory, of the April 2005 conclave that had elected Benedict XVI, when I had been in Rome with Cardinal Murphy-OConnor. Some cardinals had been making a bid to find a pastoral alternative to Joseph Ratzinger and were looking to Latin America, the Churchs new hope. A few months later, an anonymous cardinals secret diary revealed that Bergoglio of Buenos Aires had been the other main contender in that election. But after that, he had seemed to fade, to the point where almost nobody in 2013 thought he was papabile . Thats why I was so glad for that tip-off: the Argentine cardinal hadnt been on my list, or almost anybodys. At least when the balcony curtains finally opened and the new pope was announced, I could say who it was and something about him. It didnt go so well for some commentators on other channels.

Afterward, the consensus seemed to be that Bergoglio had just emerged, that there had been no group of cardinals working for his election. But if that was so, why did my old boss seem so sure, before the conclave, that it would be him? I sensed there was more, that Bergoglio had not faded at all but had simply been invisible to our Eurocentric radar, and that there had been a group organizing his election.

But that wasnt my main curiosity. What I really wanted to know was who he was, how he thought, how being a Jesuit shaped him, where he stood among all those controversies I had studied so long ago. In those first hundred days of the electrifying Francis pontificate, he had taken the Vatican, and the world, by stormflipping the omelet, as he liked to say. People were trying to fit him into straitjackets that just didnt apply in Latin America, and even less in Argentina, where Peronism exploded the categories of left and right. The misreadings had given rise to contradictory claims: A slum bishop who was cozy with the military dictatorship? A retrograde Jesuit who became a progressive bishop? Some tried to claim he was both, and had converted during his Crdoba exile in the early 1990s. Those in Argentina who knew him well said this just wasnt true. But what alternative account existed?

The first Argentine biographies, hastily assembled by journalists who had spent years reporting on him, were full of fascinating stories and insights, and this book owes much to them. But their focus, understandably, was on Bergoglios latter years as cardinal, for which there was an abundant paper and Internet trail, leaving virtually untouched his thirty years as a Jesuitthe time of the controversies, as well as the period when his spirituality and vision of the world had taken shape. What exactly had gone wrong between Bergoglio and the Jesuits? If I could understand that, I felt, it would all be much clearer.

When I met Francis for that brief minute in the hot square, I took comfort from the hand he had placed firmly on my arm. I dont mean that he wanted this biographyhe hates the idea of books about him; he wants to deflect attention to where it belongsbut the firm grip gave me encouragement: as a foreigner who had long grappled with Argentinas complexities, and knew the Jesuits, perhaps I was well placed to help outsiders understand the Francis enigma.

In October 2013, I left for Buenos Aires for an intense five weeks of interviews and research, scooping up copies of most of what he had written, much of which was long out of print. I retraced Bergoglios steps beyond Buenos Aires to San Miguel, Santa Fe, Crdoba, and Entre Ros, as well as over the Andes to Santiago de Chile. There have been other trips in the course of this book: to Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, for World Youth Day in July 2013; and twice to Rome, for the consistory of cardinals in February 2014 and the canonizations the following April of John XXIII and John Paul II. In dozens of interviews with Jesuits, ex-Jesuits, and others close to him from his twenty years as a bishop, archbishop, and cardinal, the missing narrative began to take shape. I realized that many of the important stories about Francis had not yet been told and that only by grasping the deep pastArgentinas, the Churchs, the Jesuitscould Franciss thinking and vision be understood. The Great Reformer is, necessarily, not just Bergoglios story but those other stories too.