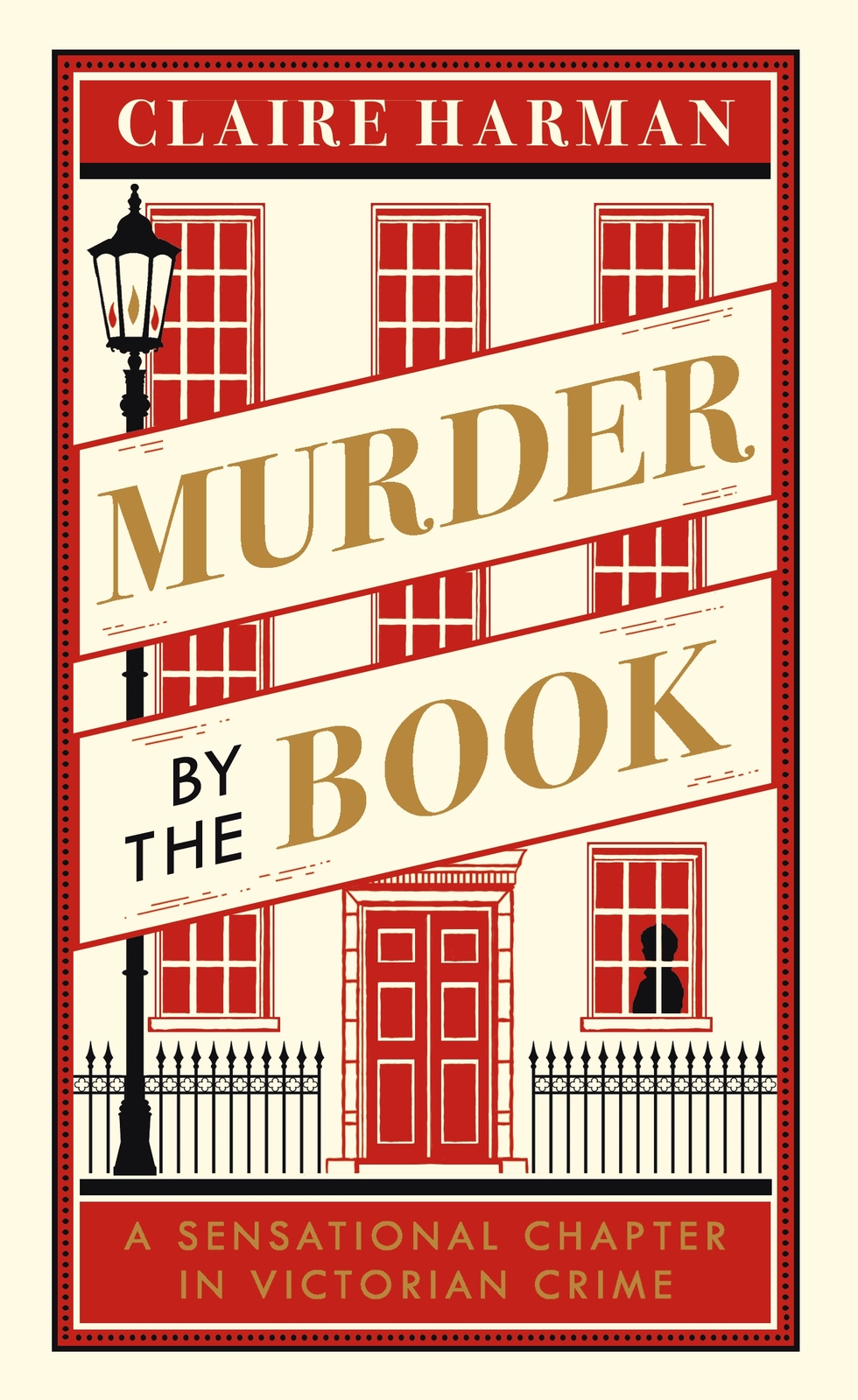

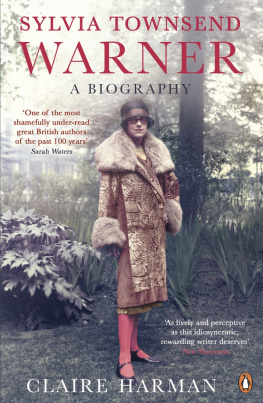

Claire Harman

MURDER BY THE BOOK

A Sensational Chapter in Victorian Crime

Contents

MURDER BY THE BOOK

Claire Harman is the award-winning biographer of Sylvia Townsend Warner (1989), Fanny Burney (2000) and Robert Louis Stevenson (2005), the author of the bestselling Janes Fame: How Jane Austen Conquered the World (2009) and of Charlotte Bront: A Life (2015). She is Professor in Creative Writing at Durham University and a Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature.

By the same author

Sylvia Townsend Warner: A Biography

Fanny Burney: A Biography

Robert Louis Stevenson: A Biography

Janes Fame: How Jane Austen Conquered the World

Charlotte Bront: A Life

There is often in effects what was never entered into intention

Examiner, 12 July 1840

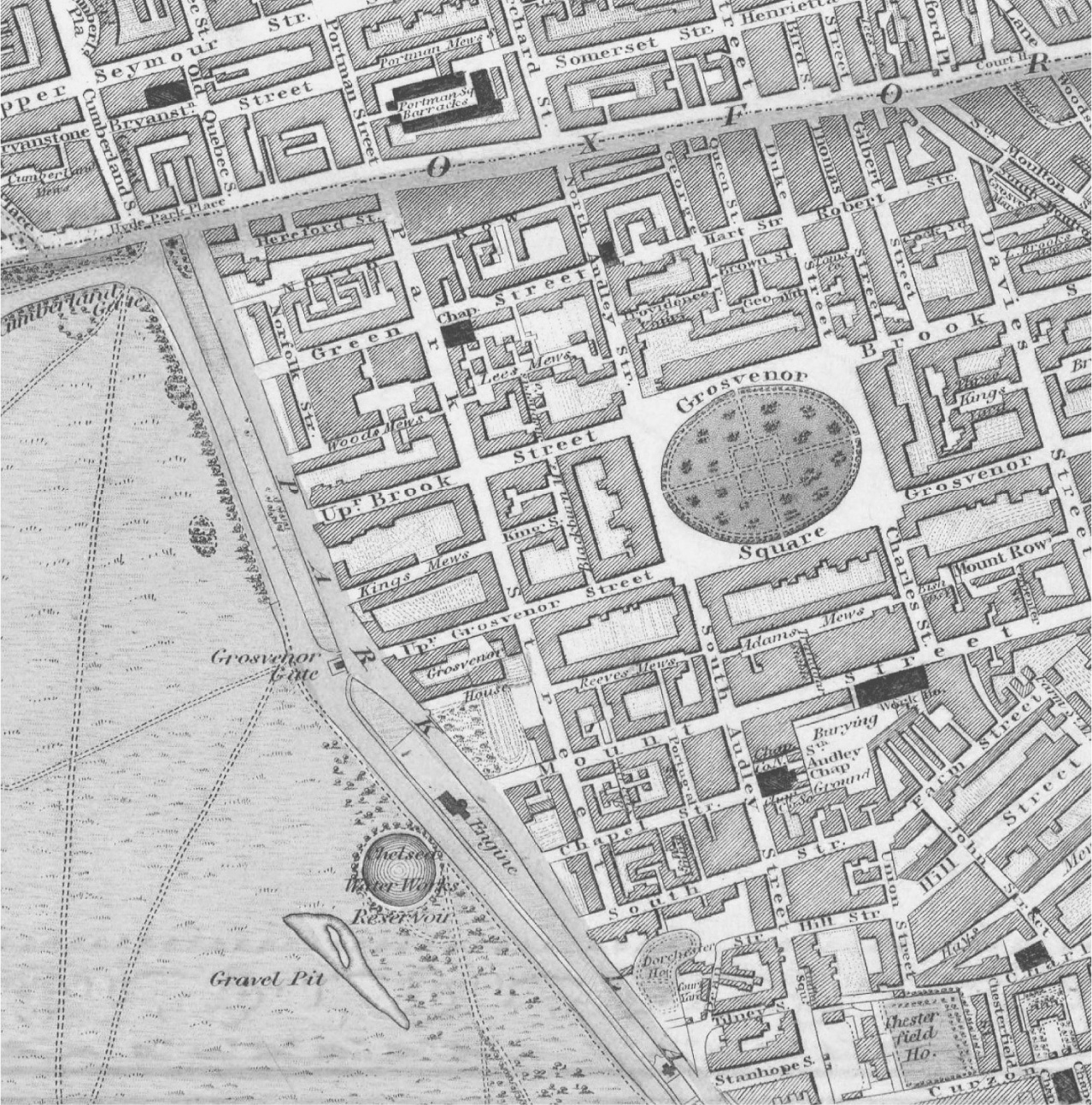

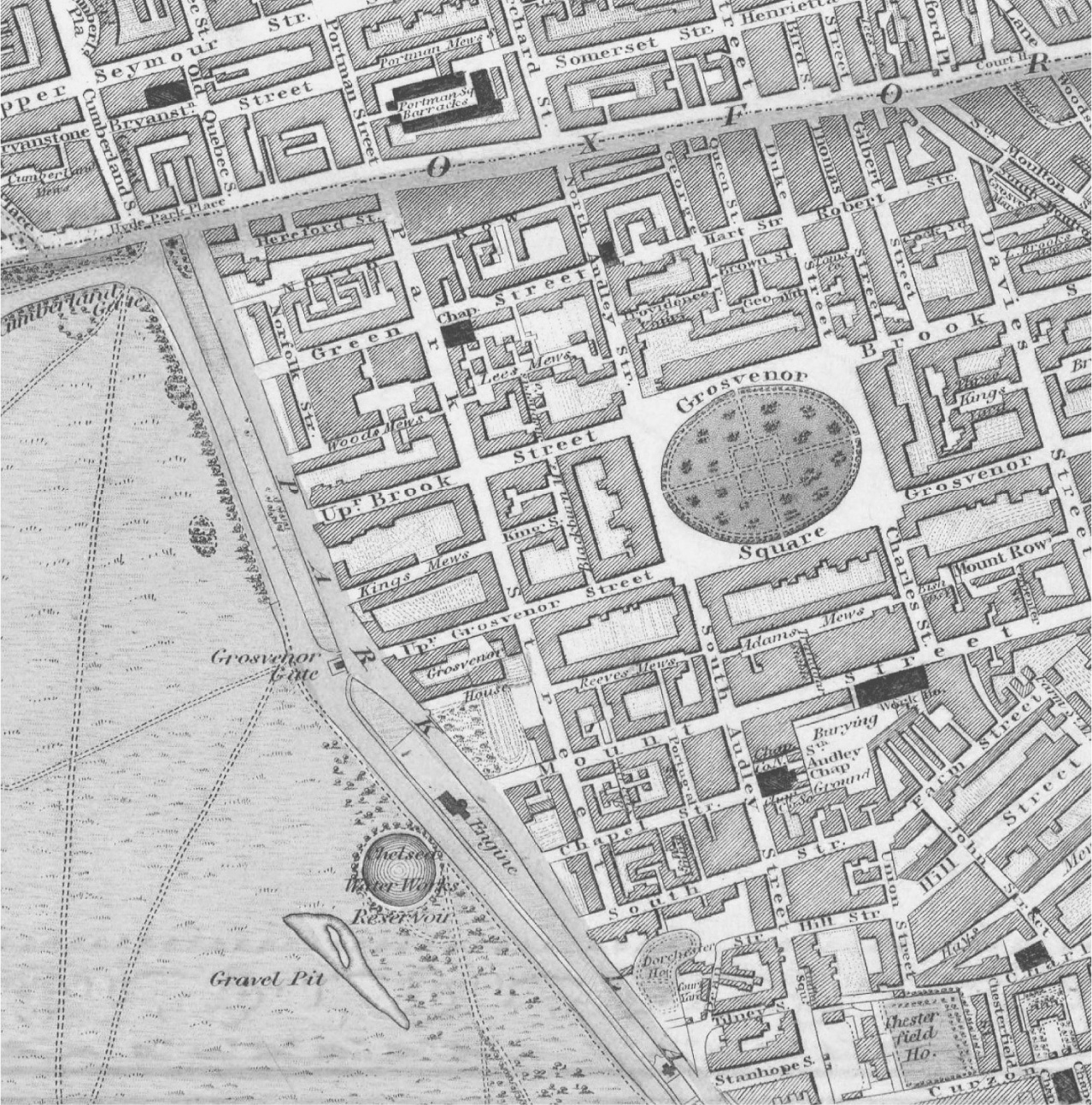

Mayfair in 1830, from a map of London by C. & J. Greenwood

List of Illustrations

. 14 Norfolk Street, Mayfair, drawn by C. A. Rivers. Lord Williams bedroom was on the second floor, fronting the street.

. Newspaper illustration of the valet discovering the crime.

. Broadside poster advertising details of the murder.

. William Harrison Ainsworth in 1834, the year of his first major success.

. Charles Dickens in 1838.

. William Makepeace Thackeray in 1839.

. Mary Anne Keeley as Jack Sheppard in the Adelphi Theatres famous 1839 production of Buckstones play.

. Sheet music for Nix My Dolly, Pals, Fake Away, with George Cruikshanks illustrations from Jack Sheppard.

. The March of Knowledge a caricature of youthful fans of Jack Sheppard: Blowd if I shouldnt just like to be another Jack Sheppard it only wants a little pluck to begin with. All five Thats all!

. Edward Oxfords assassination attempt on Queen Victoria in Green Park, 10 June 1840. The barrister Charles Phillips was an onlooker.

. Dickenss talkative pet raven, Grip, acquired while he was writing Barnaby Rudge.

. Franois Courvoisier on the first day of his trial, sketched at the bar by C. A. Rivers. Madame Piolaines evidence had not yet come to light.

. A contemporary newspaper illustration of Courvoisier in Newgate awaiting his execution.

. Madame Tussauds gruesome model of the head of Courvoisier, from his death mask.

Picture Credits

: Mayfair in 1830, detail from a map of London by C. & J. Greenwood; Harvard University Map Collection, G5754-L7-1830-G7

. Harvard Law School Library, Trials Broadsides 472, seq 187; Historical & Special Collections, Harvard Law School Library

. Harvard Law School Library, Trials Broadsides 472, seq 192; Historical & Special Collections, Harvard Law School Library

. Harvard Law School Library, Trials Broadsides 472, seq 186; Historical & Special Collections, Harvard Law School Library

. William Harrison Ainsworth by William Greatbach, after Richard James Lane, NPG D21947, National Portrait Gallery, London

. Charles Dickens by Samuel Laurence, 1838, NPG 5207, National Portrait Gallery, London

. William Makepeace Thackeray by Frank Stone, 1839, NPG 4210, National Portrait Gallery, London

. Wikimedia Commons

. George Cruikshank, cover of the sheet music for Nix My Dolly, Pals, Fake Away, Cruik 1839.7.183-q, Graphic Arts Division, Department of Rare Books and Special Collections, Princeton University Library

. The Penny Satirist, 14 December 1839, Gale Cengage Learning, document number DX1901077596

. Edward Oxfords assassination attempt on Queen Victoria by G. H. Miles, 1840, Alamy

. Free Library of Philadelphia

seq 359; Historical & Special Collections, Harvard Law School Library

. Harvard Law School Library, Trials Broadsides 472, seq 266; Historical & Special Collections, Harvard Law School Library

. Madame Tussauds

Introduction

Early in the morning of Wednesday, 6 May 1840, on an ultra-respectable Mayfair street one block to the east of Park Lane, a footman called Daniel Young answered the door to a panic-stricken young woman, Sarah Mancer, the maid of the house opposite. Fetch a surgeon, fetch a constable, she cried: her master, Lord William Russell, was lying in bed with his throat cut.

It was thought at first to be a suicide that is what the young Queen was told at noon but later that day, when her Secretary of State for the Colonies, Lord John Russell, arrived at Buckingham Palace, it was with the melancholy news that his uncle had in fact been murdered, his throat cut so deeply that the windpipe was sliced right through and the head almost severed. The motive appeared to be robbery, as the drawing room of Lord Williams house had been turned upside down and a pile of valuables had been discovered near the front door. But the brutality of the crime was what struck the twenty-year-old monarch: she wrote in her diary. It is almost an unparalleled thing for a person of L d Williams rank, to be killed like that.

Lord Williams rank did indeed make him a notable corpse, however quiet and unobjectionable a live man he had been. Third and youngest son of the Marquess of Tavistock, he had passed the thirty years since the death of his wife mostly in travel and connoisseurship. He was known at the great salons of Holland House and Gore House, the Royal Academy and at the palace itself, but his status and means were nothing to those of his nephew Francis, the 7th Duke of Bedford (owner of Woburn Abbey and its priceless art collection), nor of his nephew Lord John Russell, who was one of the most influential politicians in the land. The house in Norfolk Street where Lord William lived alone was modest by Mayfair standards and he kept only three servants, a maid, a cook and a valet. Two other employees, a coachman and groom, lived off the premises.

Who would want to butcher in his sleep this unobtrusive minor aristocrat, with his afternoons at Brookss and his restrained widower habits? In the newspaper articles that were about to appear, no one could find much to say about Lord Williams life and unoffending days as a Continental traveller and absentee MP. Aged and respected he was called in The Times, like a cheese.

But as details emerged of the murder and the bungled burglary that seemed to have provoked it, fears grew that they might be symptoms of something more widespread and insidious. For, if such a person as Lord William was not safe in his bed, in the most exclusive and privileged residential enclave in the country, who could be? Such was the panic provoked by the crime, one newspaper declared, that , and more particularly aged persons living as the deceased had done in comparative retirement, entertain, perhaps for the first time, a feeling of insecurity.

These were nervous times for the ruling classes. London in 1840 was teeming with immigrants, the unemployed, and a burgeoning working class who were more literate and organized than ever before. The winter just past had been one of mass rallies by Chartists demanding universal suffrage that in some places had turned into bloody riots, and Lord Brougham had warned at the opening of Parliament in January that the country might in fact be on the brink of revolution, so marked was the change taking place in the disposition of the common people towards

Next page

Mayfair in 1830, from a map of London by C. & J. Greenwood

Mayfair in 1830, from a map of London by C. & J. Greenwood