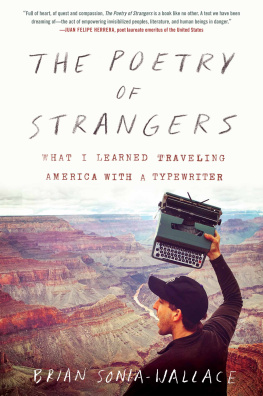

Brian Sonia-Wallace - The Poetry of Strangers: What I Learned Traveling America with a Typewriter

Here you can read online Brian Sonia-Wallace - The Poetry of Strangers: What I Learned Traveling America with a Typewriter full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2020, publisher: HarperCollins, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:The Poetry of Strangers: What I Learned Traveling America with a Typewriter

- Author:

- Publisher:HarperCollins

- Genre:

- Year:2020

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Poetry of Strangers: What I Learned Traveling America with a Typewriter: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The Poetry of Strangers: What I Learned Traveling America with a Typewriter" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

The Poetry of Strangers: What I Learned Traveling America with a Typewriter — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "The Poetry of Strangers: What I Learned Traveling America with a Typewriter" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

For my mother, who taught me to take care of stories

How do you delete?

every eight-year-old born in the twenty-first century, using a typewriter for the first time

When you are grown, no part of you

will be recognizable.

Will you tend the garden of yourself?

Do you dare brave the soil?

I sat behind a borrowed Smith Corona manual typewriter with sticky keys at a street party in downtown Los Angeles. The year was 2012, and I had recently returned to California from college abroad, another unemployed millennial at the tail end of the financial crisis, looking for a purpose but willing to settle for moving out of his parents house.

The pounding summer heat at the street party was broken by the shade of skyscrapers, glass citadels to wealth and power that towered over everyone. A new metro line had just been built in this car-powered city, and everyone was celebrating at the grand opening of the latest station. Naturally, to get there, I drove.

Helicopter moms buzzed around their children, paleteros called hielos! and pushed ice cream carts, and a homeless man shouted himself hoarse and broke down on the street corner at all these people in his living room. LA was in the middle of a homelessness crisis, a gentrification crisis, a transportation crisis. LA was perpetually in the midst of these crises.

Next to me a DJ booth, powered by solar panels, played Pharrell Williamss Happy.

I was nervous, palms sweating as I set out a Costco tray table and folding chair. Another birthday in my sputtering adulthood had passed and I had a leftover length of blue wrapping paper that I made into a sign:

POETRY STORE

give me a topic

Ill write you a poem

pay me what you think its worth

Just a week before, I had heard a story on the radio about someone selling poems in a park, and with an invitation to do something at the street party and the yearning only a twenty-two-year-old can have to make a good impression, I thought I might as well give it a try.

Whats the worst that can happen? I reasoned with my terror. No one stops, and I write poems for myself in public, like a weirdo, and go home. Ive been a weirdo before. I can do it again.

I took a picture on my iPhone of the typewriter and reluctantly put it back in my pocket, shoving down the urge to Facebook, to text, to be anywhere but here, on the hot and crowded street corner, surrounded by strangers with an open invitation for any one of them to come up and talk to me.

I idly typed on a piece of paper to calm my nerves. No sooner had I started writing than people drifted over, curious to see the typewriter and then bemused at the prospect of finding a self-proclaimed poet behind it. Do you need a poem? I asked them, from under my newsie-style flatcap. Id done acting and wore this hat like a costume, like armor. I wasnt me, I told myself over and over again, I was the character of the poet. If people rejected me, they werent rejecting me, they were rejecting this character I was playing.

But people stopped almost immediately. Old folks, to reminisce over the typewriter. Curious kids and their parents. Couples on dates. I asked each of them the same question:

Do you need a poem?

I dont have any money, replied a buzz-cut Chicana woman, with tattoos peeking out wherever clothing met skin.

Thats okay, I replied.

About my dad, then. Her answer was instant. He was a long-haul trucker when my brothers and sisters and I were growing up, so he wasnt able to be around much... She drifted into stories of her dad, her family, reminiscing about her life and relationships to a complete stranger on the street while throngs of people passed. My dad would be gone for weeks at a time, but hed do it to be able to send money home, she told me. I would just want him to know that wethat Iunderstood. And that we loved him for it.

She stopped and stood in silence. I wondered if this story was a weight shed been carrying for a long time.

My fingers struggled to muster enough force on the rusty keys of the typewriter in front of me to smash the tiny hammers into the ink ribbon and onto paper. I quickly discarded the ten-finger-typing wed been assured in school was the secret to success and went back to hunt-and-peck.

As I typed each line, the typewriter would skip ever perilously closer to the edge of the cheap TV-tray table, threatening to topple off. Id have to pause to wrestle it back, turn the knob, pull the carriage back, and start a new line. The c stuck. The spacebar sometimes skipped and left two spaces. Any hope I had at formatting the thing was goneit would format itself, thank you very much.

My index fingers labored over the keyboard. Each keystroke was an exclamation of the permanence.

I didnt keep any pictures of the poems I wrote back then, so Ill never know what the first poem I wrote for a stranger said. I remember images of truck side mirrors, endless lonely roads, buoyed by thoughts of family back home, the road itself becoming a vein through which blood flowed back to the heart. And I remember reading the poem to this fierce woman, peeking up to see her eyes closed. It was a first draft, imperfect, riddled with the errors of a sixty-year-old machine and a twenty-two-year-old poet. But it was hers.

At the end, she took a deep breath in, then opened her eyes to look at me. She took her poem, expression inscrutable.

Wait here, she said, and vanished into the crowd.

I moved on to write for someone new, a middle-aged woman in festive summer clothes who fawned over photos of her dog with me at the typewriter. But then the truckers daughter reemerged from the mass and pressed a crisp bill into my hand. I had to go to an ATM, she told me, by way of explanation. Her tone was gruff, but I could see something had softened in her face.

The truckers daughter didnt look like she had much, but her five dollars was much more than five dollars to an unemployed kid looking for something to hold on to. It was an affirmation, in this world bound by money and scarcity, this world where its hard to find the words to tell someone how you feel, what you mean. She was sending me a message:

What you are doing is worth something.

Poetry had always seemed like the most impractical of the arts, a throwback as much as the typewriter, the purview now only of English teachers and resentful students. I liked poetry but didnt love it. As a junior nerd Id proudly memorized poems from the fantasy books I read, and as a young adult had the mandatory Ginsberg Howl and Kerouac phase. I never took a poetry class in college but performed lots of student Shakespeare and grudgingly came to like that, for the theater first and the language second. If you had asked me the day before I wrote a poem for the truckers daughter, Do you love poetry? I would have said, No.

But what I made at the typewriter wasnt what Id ever thought of as poetry. It was the shrapnel interactions left behind, bits of other people buried in me, leaving me less alone. In a time when social connections were fraying, somehow poetry let me invite people in and empathize with them, whatever story they held. It was poetry that led me to discover a private America, an America where intimacy was possible, one person at a time.

At first, I was convinced it was a scam, that I was pulling a fast one getting people to pay for an index card of blank verse. Thats the dream, a palm reader I became friends with told me conspiratorially. Roll into town, make your money, and then leave! Dustbowl style. I had a vision of California in the past, orange groves teeming with newly displaced Midwesterners alongside Chinese and Mexican immigrants, workers tilling land that theyd never own. These were families uprooted from the social order and cast adrift to find new places in society. The harvest gypsies, Steinbeck called them. In the stories, thered always be the hustler, the swindler, the snake-oil salesman profiting off the hardworking folks. I wont deny there was a certain level of glee in imagining myself in this role.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «The Poetry of Strangers: What I Learned Traveling America with a Typewriter»

Look at similar books to The Poetry of Strangers: What I Learned Traveling America with a Typewriter. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book The Poetry of Strangers: What I Learned Traveling America with a Typewriter and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.