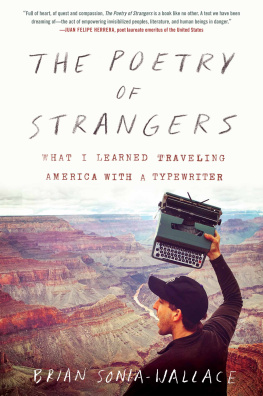

The Typewriter Revolution

Copyright 2015 by Richard Polt

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means including information storage and retrieval systems without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages.

The Countryman Press

www.countrymanpress.com

A division of W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.,

500 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10110

www.wwnorton.com

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases, please contact W. W. Norton Special Sales at or 800-233-4830.

978-1-58157-311-4 (pbk.)

978-1-58157-587-3 (e-book)

Table of Contents

Introduction

-

In a high school English class in Arizona, a student takes his favorite Royal down from the shelf and gets to work.

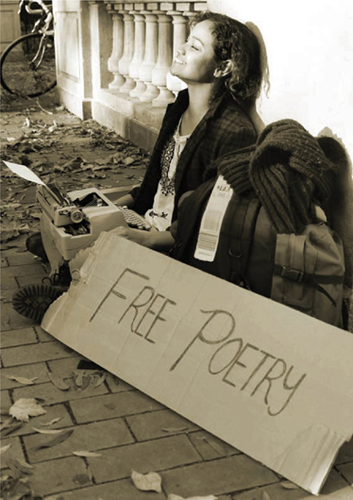

A young woman on the Venice Beach boardwalk types impromptu short stories for strangers on her Smith-Corona.

At a digital detox party in San Francisco, an Olympia helps victims of electronic overdose remember the material world.

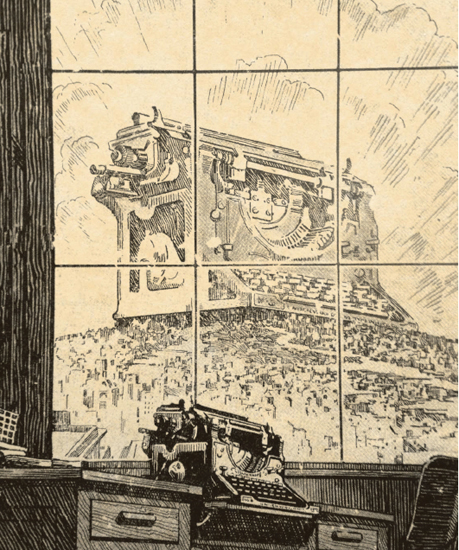

An artist in Brooklyn keeps typing until a balloon carries his page off into the sky.

From Australia to Estonia, people gather for public type-ins.

The typewriter revolution is clicking.

The typewriter has crawled back from its near-death experience, thanks to the people who use and love this machine. Who are these twenty-first-century typists? They come from all ages and groups; they speak different languages and practice many professions. But something ties them together: the love of typewriters and the will to swim against the tide. Call them the typewriter insurgencythe vanguard of the typewritten revolution.

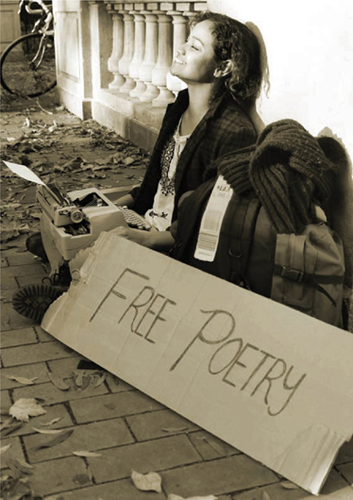

Billimarie Robinson

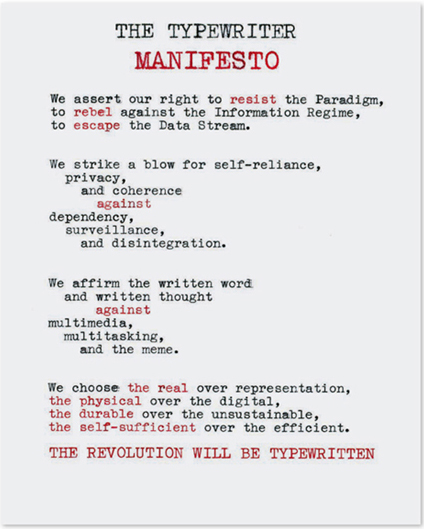

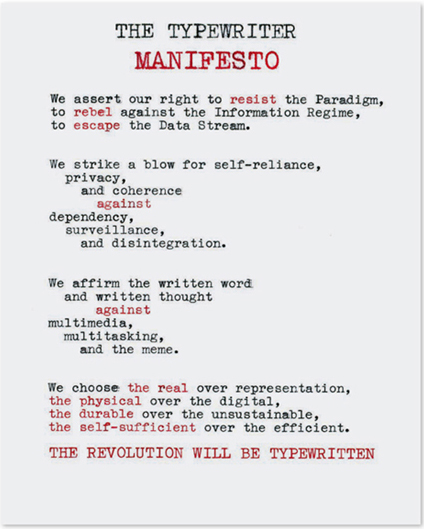

In the age of instant global information, using a typewriter is an act of rebellion. Against what? In the name of what? Ultimately, thats for you to typethe insurgency has no leader and no dogma. A typewriter has endless possibilities, like language itself. You might type a brainstorm, a journal, a letter, a story, a poem, a travelogue, a zineor use your machine to make pictures or music.

But whatever we create on our typewriters, whenever we turn to them, were choosing something that violates the digital Paradigmsomething durable, intimate, focused, and self-sufficient. When our typescripts intersect with the digital world, they arent defined by it. We rebel against the totalitarianism of the Information Regime.

This book explores the ramifications of this rebellion.

For one, consider the question of efficiency. If you typewrite in public, youre going to get some curious questions, some reminiscences, and perhaps some puzzlement from those who wont understand why youd want to do something so inefficiently. Its a fair question, and it makes you realize that typewriters today don't mean what they meant before the personal computer came along.

Typewriters used to be part of a system of efficiency. When they were first developed, they were a tool for speed and standardization. They made writing look uniform, and they churned out documents and carbon copies. To Save Time is to Lengthen Life, proclaimed the Remington Typewriter Company. Typewriters served progress, clacking away in government and commercial institutions. The typical typist was no creative writer, but a secretary skilled at transcribing the words dictated by her boss. Typewriter inventors were techies who hoped to make a mint from the march of civilization. If they were around today, they sure wouldnt be sitting at a typewritertheyd be developing apps.

Now, the typewriter is out of the system. True, most big offices still keep an electric typewriter sitting in some corner; once in a while it gets trotted out to fill out a form, type a label, or address an envelope. But for most purposes, in an increasingly paperless environment, computers are more efficient: They let you edit and share your writing far more easily, and of course they can do much more than write. Typewriters have been left in the dust.

So whats going on in that dust? The dust is a place where, dismissed from the realm of the efficient, machines can seek new identities. Its a place where the typewriter can take a rest, catch its breath, and find a way to be itselfnot just a means to an end, but a thing with its own individuality, integrity, and beauty. Its a place where we can try doing things in a new way, a place for thinking in terms other than efficiency. The dust may be fertile soil.

But why turn our backs on efficiency?

Consider where its cult has gotten us. All our efficient devices have freed up a lot of timesupposedly. But we use up that extra time doing more of the same. Matt Chojnacki, who sells and fixes typewriters in Toronto, puts it simply: The problem is that every time we save time, we find other stuff to muddle into, and we end up spending less time on stuff thats more important.

We make things so efficiently that theyre all disposable; none of them endure, none can belong to us for long before they end up on the scrap heap.

We process information so efficiently that we dont dwell on thoughts and words anymorewe flit incoherently from one set of distractions to the next.

Weve exploited the earth so efficiently that its baking in our fumes.

For a planet desperate for conservation, for a mind starved for concentration, inefficiency starts to look like nourishment and life. Maybe to save time is not to lengthen life, after all. Maybe the more efficiently you speed through life, the quicker you reach your death.

Everyone who has ever seen a typewriter displayed for sale in a thrift store will have observed small children happily thumping away at the keyboard. They do not thump at apparatus whose keybuttons produce no mechanical effect; nor will they later, as adults, think of such dead keybutton boards as being in any important way different from disposable cigarette lighters. The latter will always be empty artifacts, never interesting playthings; certainly not friends--only means to an end.

[It is] very easy for me to imagine people in the future who have no fond connection whatsoever with the past. After all, everything is being driven by the same forces--forces unlike anything seen in history, such that there is only cold laughter directed at anything built or created more than two days ago. This has profound potential consequences for a large number of human spheres, but some of the most serious are bound to be those relating to reading, publishing, spelling, written language, and that terrible word that sums up and reduces so much that is wonderful to such a freeze-dried, sterile concept: information.

Next page