Burying the Typewriter

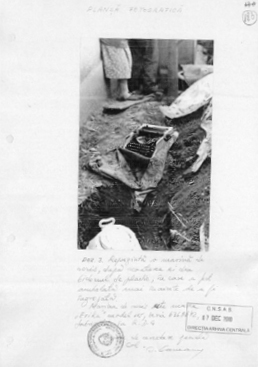

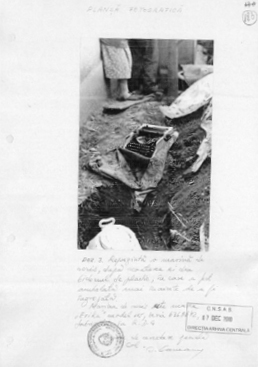

From pages in the files headed PHOTOGRAPHIC EVIDENCE

After we lifted the plastic sack we saw in the hole a plastic white container, buried 40 cm deep.

Stamp of the Socialist Republic of Romnia and the signature of Colonel Coman, in charge of penal research

Represents a typewriter, after it was taken out of its container. The typewriter is an Erika model 115, series 6368642, made in the Democratic Republic of Germany (East Germany).

The stamp of the Socialist Republic of Romnia and the signature of Colonel Coman; the stamp of CNSAS

Burying

the Typewriter

A MEMOIR

*

Carmen Bugan

Graywolf Press

Copyright 2012 by Carmen Bugan

This publication is made possible in part by a grant provided by the Minnesota State Arts Board, through an appropriation by the Minnesota State Legislature from the Minnesota general fund and the arts and cultural heritage fund with money from the vote of the people of Minnesota on November 4, 2008, and a grant from the Wells Fargo Foundation Minnesota. Significant support has also been provided by the National Endowment for the Arts; Target; the McKnight Foundation; and other generous contributions from foundations, corporations, and individuals. To these organizations and individuals we offer our heartfelt thanks.

Published by Graywolf Press

250 Third Avenue North, Suite 600

Minneapolis, Minnesota 55401

All rights reserved.

www.graywolfpress.org

Published in the United States of America

ISBN 978-1-55597-617-0

ISBN 978-1-55597-057-4 (e-book)

2 4 6 8 9 7 5 3 1

First Graywolf Printing, 2012

Library of Congress Control Number: 2012936218

Cover design: Kimberly Glyder Design

For my son, Stefano, and for my daughter, Alisa

We stood among

Those who owned their land, spoke

Of our homelands as if they were reachable

From At a Gathering of Refugees

Visiting the Country of My Birth

The tyrant and his wife were exhumed

For proper burial; it is twenty years since

They were shot against a wall in Christmas snow.

*

The fish in the Black Sea are dead. Waves roll them

To the beach. Tractors comb the sand. We stand at waters edge

Whispering, glassy-eyed, throats parched from heat.

Stray dogs howl through nights like choirs

Of mutilated angels, circle around us on hill paths,

Outside gas stations, shops, streets, in parking lots.

Farther, into wilderness, we slow down where horse

And foal walk home to the clay hut by themselves,

Cows cross roads in evenings alone, bells clinking.

People sit on wooden benches in front of their houses,

Counting hours until darkness, while

Shadows of mountains caress their heads.

On through hot dust of open plane, to my village:

A toothless man from twenty years ago

Asks for money, says he used to work for us.

*

I am searching for prints of mares hooves in our yard

Between stable and kitchen window, now gone

With the time my two feet used to fit inside one hoof.

We sit down to eat on the porch when two sparrows

Come flying in circles over the table, low and fast, happily!

My grandparents souls I think aloud, but my cousin says:

No, the sparrows have nested under eaves, look

Past the grapevine. Nests big as cupped hands, twigs

And straw. Bird song skids in the air above us.

Into still-remaining rooms no sewing machine,

Or old furniture with sculpted flowers on walnut wood.

No rose bushes climbing window sills, outside.

And here, our water well, a vase of cracked cement. Past

Ghosts of lilac, pear, and quince in the sun-bitten yard I step

On re-imagined hooves, pull the chain, smell wet rust.

Unblemished sky ripples inside the tin bucket,

Cradled in my arms the way I used to hold

Warm goose eggs close to skin so not to break them:

The earth will remember you my grandparents once said.

Here, where such dreams do not come true, I have come

To find hoof-prints as well as signs from sparrows.

Romnia, July 2010

Foreword

It is fairly common these days to find a preponderance of agony memoirs in a pile of nonfiction manuscripts. Suffering seems to sell, so why not have a go at it? one might ask. Well, it can be tiresome, for one thing. For another, suffering in itself is not interesting. If such a memoir is to float, the suffering must be part of something larger and more significant than itself. It must be wound into a larger context, a life in a world, a world with a history. And, more than this, that world should be exposed without self-pity, and without a hint of self-righteousness either.

Such a world is the one described in Carmen Bugans Burying the Typewriter Romnia in the clutches of its Communist rulers. Here is a world in which Bugans father, a celebrated anti-Ceauescu activist, is not to be veered off the path of righteousness. Even when he is safely out of Romnia and in exile in Michigan, his prize photograph in the family album remains the one focused on himself. It is the one in which, as his daughter describes it, he reenacted his protest against Ceauescu [leaving] us to Gods will and the secret police.

It is the children of political dissidents who can have the hardest time of it. Not only must they compete for their parents attention with a cause higher than themselves, but they may also find themselves seriously endangered by the cause their parents champion, suffering, at the very least, the disapproval, suspicion, and hostility of their acquaintances, and, at the worst, starvation, abandonment, and death.

And yet the children themselves can be torn. In Bugans case, there is both resentment and love for a father who, one moment, might romp joyously with his children in the sea, or row them out to Ovids island, scene of the poets exile; in the next, endanger them by typing antigovernment pamphlets on an illegal typewriter; and, in yet another, stagger forward in prisoners chains, tearful at the sight of his starving daughter.

Because the family is endangering the whole village, its members are treated like pariahs by all but the decent few. One of the latter is the literature teacher, who imperils herself by taking the starving Carmen into her office each day to give her a sandwich she has hidden in her handbag. I can show no gratitude except by eating her food. With time, she will become the reason I believe that literature truly nourishes the hungry. She will become the reason I love morphology and syntax. I will never, for the rest of my life, know or love a teacher more.

By contrast, the history teacher orders Carmen to stand up in class, declaring, Your father is a mentally ill criminal who is destroying your future. On the playground, the other children, encouraged by the teacher, taunt her and throw stones at her, calling her daughter of criminal.

Then there is the blame, the rage leveled at the father by the family itself. At the age of seventeen, Carmen tells him, I never wanted to be part of your vision. You just took our support without even as much as a word of thanks. And she is not alone. Her mother, someone whose ambitions have never leapt higher than to walk the length of our village and be greeted warmly by everyone, also finds it hard to forgive him.