TOBIN T. BUHK

vii

Chapter 1 13

Chapter 2 24

Chapter 3 31

Chapter 4 45

Chapter 5 58

Chapter 6 74

Chapter 7 85

Chapter 8 109

Chapter 9 125

Chapter 10 136

Chapter 11 148

Chapter 12 161

Chapter 13 180

Chapter 14 206

Chapter 15 219

Chapter 16 240

11 is fair in love and war, but during every conflict there are those who go too far, those who cross an often invisible boundary between what conduct is considered appropriate and what is not. The United States Civil War was no different.

11 is fair in love and war, but during every conflict there are those who go too far, those who cross an often invisible boundary between what conduct is considered appropriate and what is not. The United States Civil War was no different.

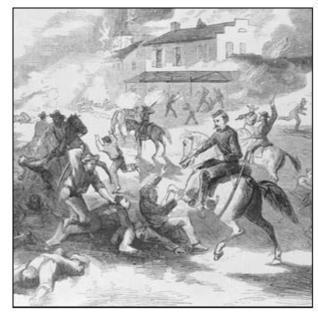

The four-year period of hostilities that began in 1861 gave rise to leaders who used their positions for personal gain; profiteers who tried to make money off of misery; generals who dueled other generals, even though they were on the same side; ruthless raids targeting civilians and their property; and bandits who used the conflict as a convenient excuse to rape, pillage, and murder. Sometimes these malefactors got away with these crimes, and sometimes they didn't.

The Great American Divorce: A Note about Voices

Whenever a divorce occurs, especially one involving custody issues, strong opinions tend to result. People take sides. Fingers are pointed. The Civil War was the biggest divorce in the nation's history. And it involved custody issues.

People took sides. Accusations, expletives, and shells flew, although not necessarily in that order. Later, many of the combatants lucky enough to survive the bullets and the grapeshot wrote about their experiences. This amazing legacy has survived in countless diaries and books.

For the writer, this material is a blessing as well as a curse. It's a blessing because there is nothing more compelling than listening to voices from the past telling their stories. Reading the archival material from the era is the next best thing to taking a time machine for a spin back to 1863. It's a curse, because as authentic as they are, these voices are not always honest. At times, they embellish or even downright lie. Sometimes, they're mistaken or inaccurate. And sometimes, they point the finger and sling accusations as if they're firing at the enemy.

Newspaper reports don't help much in sifting fact from allegation. The news reporters of the era didn't tell it like it was, but rather as they saw it. They didn't bother with "allegedly" this or "reportedly" that. They came out and proclaimed guilt or innocence in ways that would make a twentyfirst-century editor cringe.

No one, except perhaps the historian who doubles as a clairvoyant, can claim to know firsthand what happened 150 years ago. The next best thing is to find as many voices as possible from both sides and discern some middle ground between them.

The following chapters were constructed, as much as possible, using the voices of the people who lived through this turbulent era and survived to write about it. Please remember, they sometimes present myth as fact, sometimes lie, frequently exaggerate, often make mistakes, and almost always contain a bias. The author has tried, in earnest, to do none of these things.

A Brief Note about Cases

Beggars can't be choosers, except when dealing with the Civil War. There were so many Civil War-related crimes that no single volume could do it justice. Alas, choices had to be made.

The following crimes were selected because they were some of the most audacious, brutal, bodacious, or bizarre cases, representing all points on the criminal spectrum. Many contain uniquely devious twists: a riot that began with a crime that later turned out not to be a crime; an outlaw-onpaper who became so real, he was hanged; guards allegedly so sadistic from a prison so infamous, they wound up on trial; a group of terrorists whose plan went up in smoke instead of their intended targets; and a little general whose libido did him in.

And now, on to the mayhem.

wo boys ambling down Pennsylvania Avenue in Washington, DC, paused at the corner of East First Street. They stared, mouths agape, at the imposing building across the street-the Old Capitol Prison-hoping to catch a glimpse of an inmate behind the barred windows. Captivated, the kids failed to hear the guard yelling at them: "You there, hurry up."

wo boys ambling down Pennsylvania Avenue in Washington, DC, paused at the corner of East First Street. They stared, mouths agape, at the imposing building across the street-the Old Capitol Prison-hoping to catch a glimpse of an inmate behind the barred windows. Captivated, the kids failed to hear the guard yelling at them: "You there, hurry up."

The boys were unaware as they studied the three-story edifice that they were about to get an inside look at Washington's most notorious landmark. Quick to act when the boys failed to respond to his warning, the corporal ran down the street, collared the two twelve-year-olds, and escorted them inside the prison for questioning as "suspicious persons."'

The entire scene, which took place on a chilly, cloudless winter afternoon in 1863, was witnessed from the arched window of Room 16, where James Williamson spent two months as a "suspicious person." Williamson, who worked for a local printing firm, was arrested on January 31, 1863, after ret urning from a trip to Richmond. When he refused to take the oath of allegiance to the Union, he wound up inside the Old Capitol, so named because the structure was built as a temporary capitol after the British burned down the original building during the War of 1812.

Williamson, who occupied the room with several other "suspicious persons," passed time by watching the foot traffic on the street below the window of his cell. During his brief incarceration, he witnessed many incidents in which the guards chased away or even arrested passersby on suspicion of attempting to deliver messages to the silhouettes behind the bars.

11 is fair in love and war, but during every conflict there are those who go too far, those who cross an often invisible boundary between what conduct is considered appropriate and what is not. The United States Civil War was no different.

11 is fair in love and war, but during every conflict there are those who go too far, those who cross an often invisible boundary between what conduct is considered appropriate and what is not. The United States Civil War was no different.

wo boys ambling down Pennsylvania Avenue in Washington, DC, paused at the corner of East First Street. They stared, mouths agape, at the imposing building across the street-the Old Capitol Prison-hoping to catch a glimpse of an inmate behind the barred windows. Captivated, the kids failed to hear the guard yelling at them: "You there, hurry up."

wo boys ambling down Pennsylvania Avenue in Washington, DC, paused at the corner of East First Street. They stared, mouths agape, at the imposing building across the street-the Old Capitol Prison-hoping to catch a glimpse of an inmate behind the barred windows. Captivated, the kids failed to hear the guard yelling at them: "You there, hurry up."