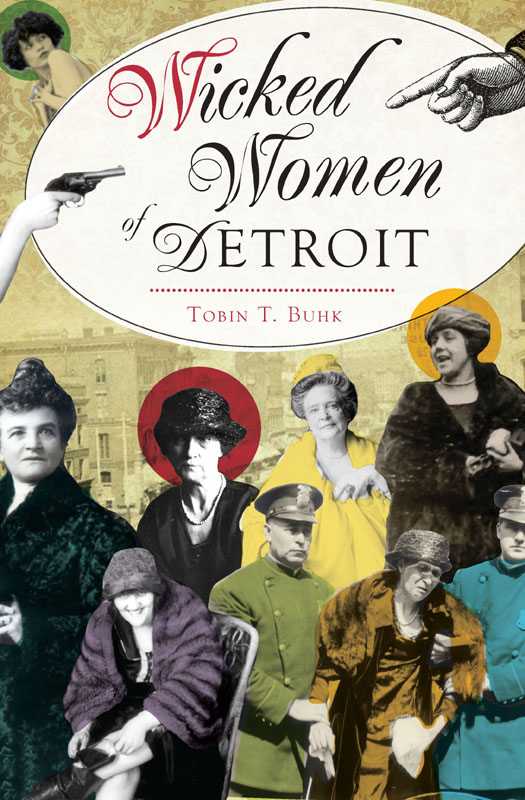

Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC

www.historypress.net

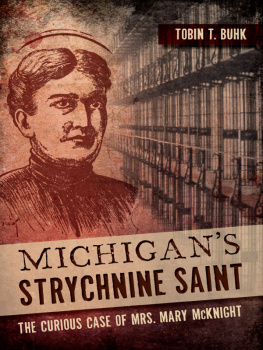

Copyright 2018 by Tobin T. Buhk

All rights reserved

First published 2018

E-Book edition 2018

ISBN 978.1.43966.540.4

Library of Congress Control Number: 2018945678

Print edition ISBN 978.1.46713.845.1

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

CONTENTS

2. Blood Feud:

The Lewis-Lyons Go-As-You-Please Match (1882)

7. Crystal Balls:

Mother Elinor and the Flying Roller Colony (1907)

Introduction

SOMETHING WICKED

THIS WAY COMES

MURDER IN WAX, CIRCA 1899

Detroiters love a good murder mystery. They always have, long before Detroit became the Motor City and even longer before it earned the dubious nickname Murder Capital. This fascination with horrific homicides goes back to the gaslight era, when the most popular attraction in the city depicted grisly recreations of murder and mayhem in wax.

This captivation with crime was evident in the long lines leading out of the Wonderland, an amusement complex located at corner of Woodward and Jefferson. The most popular attraction was the first-floor Chamber of Horrorsa wax museum that re-created the late nineteenth centurys most heinous crimes with near photorealism. The blood-spattered exhibits contained around a dozen tableaus peopled by over one hundred wax villains. The flickering of dim gas lanterns added to the sinister aura.

As visitors strolled through the galleries, they could witness Kemmler strapped into the electric chair moments before the executioner turned on the juice; the room of Mrs. Mary Latimer, murdered by her son Robert, as it appeared the day after police found her body propped against a chair in the bedroom of her Jackson home; a Port Huron lynching victim dangling from a tree; and other ghastly scenes.

Museum manager M.S. Robinson, a former lawyer from Chicago, had a knack for staging scenes so revolting that the citys more puritanical succeeded in shutting the wax museum down in 1890. After the mandated closure, Robinson reopened the Chamber with new and even bloodier scenes.

Detroiters loved it.

They spent hours studying the grim exhibits. It became so popular, particularly among women, that Robinson kept the Chamber open from 10:00 a.m. to 10:00 p.m. and enlarged the accommodations for ladies.

While Detroits upstanding women watched their greatest nightmares materialize in wax, Michigans most dangerous women lived and worked in the citys real Chamber of Horrors. The womens wing of the Detroit House of Correction housed sadistic serial killers, wives who murdered their husbands for insurance money, con artists, madams, prostitutes, shoplifters and others.

THE WOMENS WING AT THE OLD DETROIT HOUSE OF CORRECTION, CIRCA 1899

On the eve of the twentieth century, the Detroit House of Correctionone of four state penitentiaries at the time and Michigans sole institution for long-term female inmatescontained sixty-five women serving sentences that varied from several weeks for violations of minor city ordinances to life for the big M. At any one time, the old House held about two to three women serving life sentences, and over its life span, from 1861 to 1926, it housed about three dozen women serving the maximum penalty allowed under Michigan law. Prison authorities did not segregate female inmates by crime, so these felonsthe most dangerous women in Michiganrubbed elbows with short-timers.

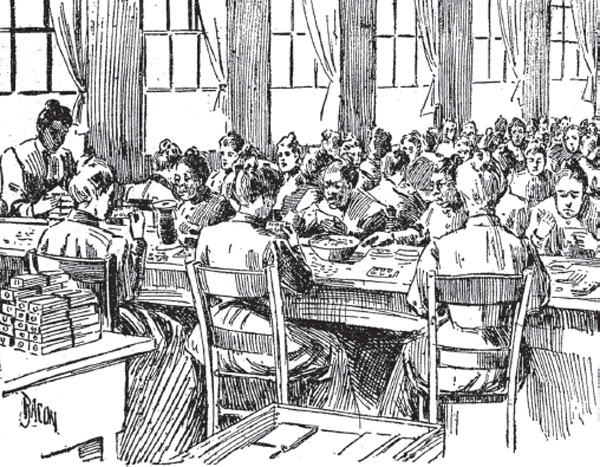

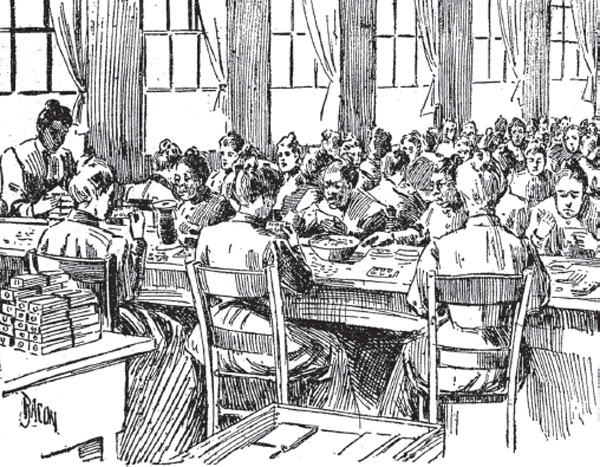

A Detroit Free Press article, written by a reporter who visited the Womens Wing of the House of Correction in 1899, captured a scene of the citys most wicked women paying their debts to society in one of the prison shops.

The women sat facing one another on long wooden benches, their flannel prison-issued dresses draping to the floor. An occasional whisper rose above the din, but this was a rarity since the prison matrons strictly enforced the silence rule. Their fingers jerked spasmodically as they sewed buttons onto cardsthe partial penance they paid for prostitution, public drunkenness, theft and murder. Sunlight streamed in from a line of windows and fell onto the tables, and at least once during the shift, each one gazed through the bars at the world on the other side of the whitewashed brick wall.

A Detroit Free Press artist sketched this scene of women inmates hard at work inside the House of Corrections prison shop in 1899.

The inmates all wore the same prison-issue garb, but they all took different paths into this room.

Although serious offenders once known in the papers as Pope, Echols, Roberts and Lawrence had swapped their surnames for inmate numbers and had disappeared from the public eye behind layers of brick and iron, they remained subjects of curiosity for years after the papers documenting their crimes had yellowed.

Nellie Pope, who conspired to murder her husband in 1895, frowned as a matron led a reporter into the factory. The matron thought it best to walk past the volatile Pope, known to use physical violence if she felt threatened. A head taller than the other inmates, the statuesque Pope was an intimidating and frightening figure best left alone.

Tucked into one corner of the room, Fanny Echols, whose murder of her husband fifteen years earlier led to a life sentence, toiled away at the buttons. The writer described Echols as a buxom good-natured looking colored woman.

Woman inmates of New Yorks Sing Sing Prison pose for a photographer, preserving for posterity the prisoners couture, circa 1870. Their sisters inside the big house in Detroit wore nearly identical prison-issued outfits, while the matrons wore all black. This stereograph formed part of a series, Hudson River Scenery, by photographer Gustavus W. Pach. Authors collection.

Next to Echols sat convicted thief Dora Roberts. Dora and her husband, Walter, robbed a Champlain Street saloon owner of $200. A constable in the right place at the right time caught Dora with her hand in the cookie jar when, as he chased her out of the saloon, she dropped a roll of stolen greenbacks into a spittoon.

Alice Lawrence, who received twenty years for conspiring to murder her husband in Holland, raised her head and watched as the reporter slowly passed her bench. When their eyes met, Lawrence felt a pang of shame and quickly dropped her head.

San Francisco Police mug shot of a notorious check forger from Detroit who went by several aliases. A repeat offender, she went to San Quentin in 1908 following her second California arrest. Before the advent of protective features on fiscal paper, check forgery became a popular endeavor among early twentieth-century women offenders, and such petty criminals made up the majority of female inmates inside the old Detroit House of Correction.

Next page