I am indebted to the staff at the Library of Michigan. The archivists there have done an incredible job of preserving and indexing the voluminous criminal records from 19th-century Detroit. They helped me locate Sophies Detroit criminal records and the appeal of her will. Without those resources this book could not have been written.

I appreciate the assistance I received from the staff at the London Metropolitan Archives in London, England, and the Surrey History Centre in Woking, England. Staff there located the records related to some of Madeline Belmonts hospitalizations.

The New York State Archives in Albany gets my thanks for locating the reformatory records of George Lyons and the prison records of Jim Brady.

Thanks to Jerry Kuntz for sharing with me the records of the Pinkerton Detective Agency held at the Library of Congress.

I am very grateful for the excellent editorial assistance I received from Jen Tebbe.

To my friends Anne DeMarinis and Melanie Killen go my thanks for their willingness to listen to my concerns and for their sage advice.

Last but definitely not least, I thank my husband, John Fink. He accompanied me on many research trips and he carefully held down yellowed, curling papers while I photographed them. He listened to more stories about Sophie Lyons than anyone without a substantial interest in crime history should ever have to hear. With his patience and support, he is my rock.

Preface

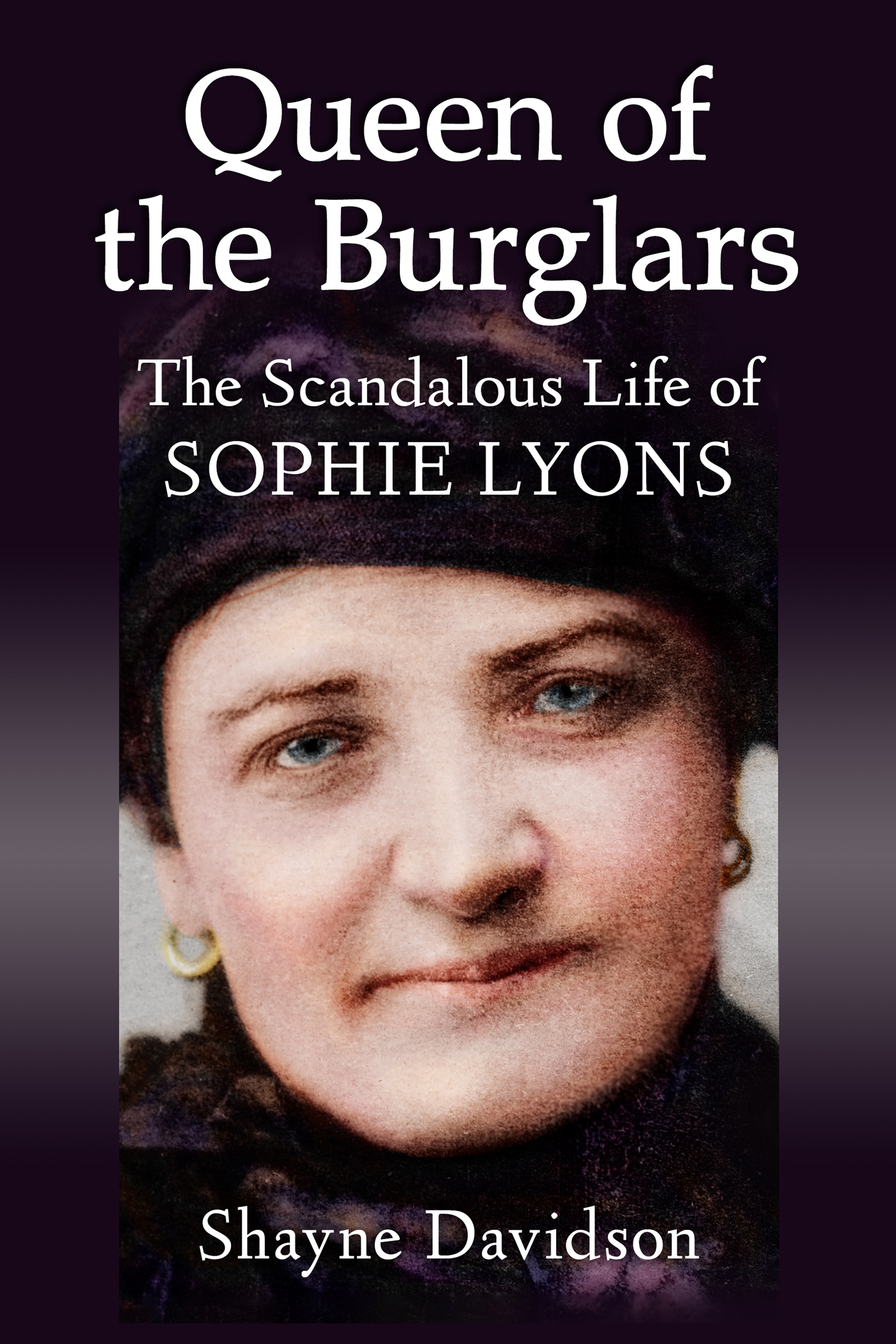

One of the most renowned professional criminals in 19th-century America was a woman named Sophie Lyons. In 1913 she published a book about her life titled The Amazing Adventures of Sophie Lyons, Queen of the Burglars, or Why crime does not pay . (The title was shortened to Why Crime Does Not Pay for the hardbound edition of the book.) Its filled with entertaining anecdotes about crime, stories of her adventures, and the escapades of her friends and lovers. Some of the books more sensational stories were even published in newspapers as stand-alone articles.

Sophie was a con woman, among other things, and the stories she told about her life were generally a little truth woven together with a pile of lies. After she died, the press regurgitated Sophies exaggerations and fantasies. Ultimately so much questionable information was written about Sophies life and crimes that I wondered whether it would be possible, nearly 100 years after her death, to research her background and discern the true story of her unconventional life.

I began my research by creating a family tree for Sophie from genealogical sources such as the U.S. Census and records of births, immigration, marriages, and deaths. While I was in the process of making the family tree, I noticed the listing of a book for sale at a rare bookshop in Detroit: a first edition of Professional Criminals of America by Thomas Byrnes.

Byrnes, a poor Irish immigrant, grew up in the notorious Five Points slum in lower Manhattan. In 1863, when he was 21 years old, he joined the police force and rose quickly through the ranks. New York City centralized its detectives under one roof in 1882 and the following year Byrnes was appointed the head of the Detective Bureau. Three years later he published his magnum opus, Professional Criminals of America . The book contains photos and biographies of 204 seriously bad men and women, including Sophie.

As it turns out, the first edition for sale in Detroit once belonged to someone named Florence L. Bower. Florence had written her name in neat script in the front of the book. Because Sophies family tree was fresh in my mind, I realized that the book had probably belonged to Sophies oldest daughter, Florence Lyons Bower. It was such a bizarre coincidence that I felt compelled to go to the shop. Once there, I carefully looked over the book, decided it was legit, and purchased it.

Around 1877, Sophie moved from New York City, where shed spent much of her childhood, and established a home base in Detroit, which was where Florence lived the majority of her life. Although theyd been estranged for years, Sophie reached out to Florence shortly before she died, in 1924, and told her that shed made a new will. The updated document specified that many of her household possessions and some of her real estate were earmarked for Florence.

Its entirely possible that my copy of Professional Criminals of America once belonged to Sophie and Florence inherited it. After all, it contains a number of notations in a hand other than Florences. In the section near Sophies photo and biography, the pages have been so well perused that the binding is loose and falling apart. My copy of the Byrnes book and some of the notations in it became an inspiration for this book.

Additional discoveries followed on the heels of finding Florences book. For example, I purchased a rare photograph of another of Sophies daughters, Lotta Belmont, on eBay. I also found that some of the original court records related to Sophies life and crimes in Detroit have survived. These materialssome of which are now almost 140 years oldhave been archived at the Library of Michigan in Lansing.

News stories written as close to the time and place of a particular event or crime provided the information I found to be the most reliable. Reporters from the Detroit Free Press attended Sophies many hearings and trials in the 1880s, and they took shorthand of witness statements. Those notes evolved into articles that often included lengthy verbatim testimony.