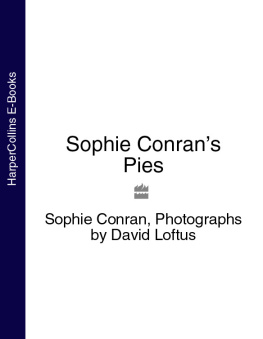

Sophie

Copyright 2012 by Emma Pearse

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. For information, address Da Capo Press, 44 Farnsworth Street, 3rd Floor, Boston, MA 02210.

First edition published in the US. This edition published by arrangement with Hodder & Stoughton, an Hachette UK company. First published as Sophie: Dog Overboard in Australia in 2011 and Great Britain in 2012.

Typeset in Plantin Light by Hewer Text UK Ltd, Edinburgh

Cataloging-in-Publication data for this book is available from the Library of Congress.

First Da Capo Press edition 2012

ISBN 978-0-7382-1467-2

ISBN 978-0-7382-1548-8 (e-book)

Published by Da Capo Press

A Member of the Perseus Books Group

www.dacapopress.com

Da Capo Press books are available at special discounts for bulk purchases in the U.S. by corporations, institutions, and other organizations. For more information, please contact the Special Markets Department at the Perseus Books Group, 2300 Chestnut Street, Suite 200, Philadelphia, PA, 19103, or call (800) 810-4145, ext. 5000, or e-mail .

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For Biggles, Poppy, Harmony, Groo, Molly, Molly, Chloe, Lucy, and Oscar

For Ruby

For Sophie

Contents

It was a warm Sunday evening at the end of March 2009 and the sun was setting over the coral reefs and hundreds of tropical islands dotting Australias north Queensland coast. On the small island of St. Bees, thirty-odd kilometers offshore of Mackay, a small crew of national park rangers and research scientists looked out across the beachfront and saw a dog. Or rather, the silhouette of a dog, a mid-sized wolfish one, trotting along the shoreline. The dog was outlined against the giant orange sun and the darkening ocean, its head hung down and forward, its tail straight out behind.

There it is, ranger Steve Burke said to scientist Bill Ellis.

Lone dog in the wild, Bill replied.

Bill couldnt help but marvel at the sight. It was like a scene from The Call of the Wild out there, the dog gliding through the landscape, seemingly oblivious to the men. It appeared to be determined to keep its distance and follow its solitary path.

Bill, who had been studying the islands koala population since 1998, had just spent the day coaxing koalas out of trees in the islands densely bushy hills. Seeing the running dog on St. Bees, though, was an unwelcome novelty. There were wallabies all over the island and there were still plenty of goats, descendents of the animals that were introduced more than a hundred years ago. But by 2009, the approximately three-square-mile island was almost all national park, and protected from both human development and non-native animal species on account of its abundant birdlife, from sacred kingfishers to sea eagles and kites, as well as its occasional snake, and lots of (mostly harmless) spiders.

This dog had no business being on the virtually uninhabited island, in a zone where domestic pets were prohibited. Neither Steve nor Bill was surprised to see it, though. Steve had been aware of the dog for weeks, ever since David Berck, one of the leaseholders of St. Bees only private section, Homestead Bay, called to let him know that there was a dog roaming the island and that it seemed to have come over from Keswick Island, St. Bees neighbor. Some of Keswicks fourteen or so residents had also spotted the dog in December, and then later noticed it on St. Bees, which was clearly visible over the narrow but rough ocean channel of Egremont Passage, a few weeks later.

The dog had seemingly been out there for months, yet no one had reported their pet missing. There had been no call to Mackay office of the Queensland Parks and Wildlife Service from distressed dog owners reporting that they had lost their beloved pet while out boating. Of course, it had been known to happen: picnicking locals would head out to the islands, their dogs would get lost in the bush and the owners would have to leave them behind in order to catch the tides back to the mainland. But they always alerted the authorities. So for the last few months, Steve and his colleagues had been baffled as to where exactly this dog could have come from and exactly how they should deal with it.

Now, out on St. Bees for the first of several annual trips that the Mackay-based rangers made in their supervision of the island, Steve Burke was on a mission. It was time to finally trap this dog. Trapping was the most humane way that he and his fellow rangers, most of them dog lovers with dogs of their own at home, could think of to remove this mysterious animal, who posed a threat to every species on the islands.

But it wasnt going to be easy. The dog had already eluded several attempts by St. Bees sole resident, Peter Berck, to befriend it, tempting it out with cans of dog food. It was giving every impression that it wanted to be left alone, and there were a whole lot of places on St.

Bees for it to hide. The island is craggy and volcanic, approximately 2.5 miles from shore to shore and shaped like a cartoon egg that has been hastily cracked into a pan. The rangers were only out on the island for four days of solid work and, if they werent able to lure the dog into the wire trap theyd borrowed from the Mackay Regional Council, Steve knew they were going to have to use more drastic measures. Nobody wanted to take that thought to its conclusion, but the fact was, this dog couldnt be here. If it was behaving antisocially, it could be dangerous. If it was feral, they might have to put it down.

So, the first step was to set the trap in a place the dog was likely to venture to. While there were plenty of spaces to harbor itself, in order to leave St. Bees, the creature would have to swim. Steve was counting on it being smart enough to know this, as well as hungry enough to sniff its way into the trap. He and his ranger colleague, Ludi Daucik, hopped into the inflatable dinghy sitting on the shore and headed out to their boat, Tomoya. Between them, Steve and Ludi maneuvered the empty but hefty metal trap from Tomoya to the dinghy and then motored back to St. Bees. They pulled up beside a rusted line boat that lies on Stockyard Bay, emerging and receding with the tides, looking almost as if its had a bite taken out of it by one of the hammer-head sharks that live off the reef.

The two men picked a patch under a low-hanging beach-scrub tree above the high tide mark just back from the shore between Honeymoon and Stockyard Bays. It was one of the few sheltered spots visible from Peters house on Homestead Bay. Steve set about filling a burlap bag with the sloppy contents of several cans of dog food that hed picked up from the supermarket. Hed bought the fancy beef and gravy recipe, thinking, this has gotta do the job. His mind on his kelpie and border collie cross playing safely at home in his Mackay backyard, Steve swished the food around, making sure the gravy seeped into the bag so that the scent would travel further towards this hungry castaway dogs nostrils. He tied the bag to a spring mechanism at the far end of the trap. Any pressure on the burlap bag and the trap would fall down behind the mysterious hound.

After that, there was nothing to be done except to head back to Tomoya and get settled for the night. Steve, for one, was looking forward to relaxing in front of the TV, while Bill was ready for a beer.

Next page