PENGUIN BOOKS

UK | Canada | Ireland | Australia

New Zealand | India | South Africa Penguin Books is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com. M. M.

Bowra, 1969 All rights reserved ISBN: 978-0-241-24197-4

THE BEGINNING

Let the conversation begin Follow the Penguin Twitter.com@penguinukbooks Keep up-to-date with all our stories YouTube.com/penguinbooks Pin Penguin Books to your Pinterest Like Penguin Books on Facebook.com/penguinbooks Listen to Penguin at SoundCloud.com/penguin-books Find out more about the author and

discover more stories like this at Penguin.co.uk PENGUIN CLASSICS

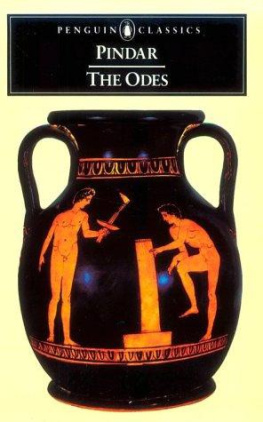

THE ODES OF PINDAR

ADVISORY EDITOR: BETTY RADICE

Pindar was born in 518 B.C. near Thebes in Boiotia of an aristocratic family which sent him in boyhood to study music and poetry at Athens. When he was only twenty he was commissioned by the royal house of Thessaly to write

Pythian X, and he soon found patrons in many parts of Greece and in Sicily, which he visited in 476. Pindar and the aristocratic families with whom he was at home in most parts of Greece, particularly in Aigina, were little interested in the new ideas which Athens was enforcing on Greek cities. When Pindar praised his own special world in 474 he was reprimanded and fined at Thebes. He realized how dangerous Athens was to his kind of society when, after 460, first Aigina, then Boiotia was conquered.

Pindar reached the height of his fame and found the fullest scope of his powers in the seventies and sixties of the fifth century. He died at Argos c, 438. In antiquity his poems were collected in seventeen books, from which survive, more or less intact, four books of Epinician Odes choral songs written in honour of victories in the great Games. Sir Maurice Bowra studied Greek at Oxford under Gilbert Murray and gained first class honours. In 1922 he became tutor and fellow of Wadham College, Oxford, and in 1938 he was made Warden, a post which he retained until his death in 1971. From 1946 to 1950 he was Professor of Poetry in the University, and from 1951 to 1954 he was its Vice-Chancellor.

From 1958 to 1962 he was President of the British Academy. He wrote a number of books on Greek subjects, but also extended his studies to include parts of other literatures. He travelled a great deal in Greece, Asia Minor, and the Near East, and the United States. He was knighted in 1951, became a Commander of the Legion of Honour, a Doctor of Letters of Oxford University, and was the holder of eight honorary doctorates.

Preface

In 1928 Professor H. T.

Wade-Gery and I published with the Nonesuch Press a little book, Pindar: Pythian Odes. This contained translations of all the Pythian Odes, together with a general introduction and separate introductions to the individual poems. The book, which was charmingly produced, very soon sold out and has not been reprinted. After forty years I have gone back to it and tried to make it the core of a complete translation of Pindars Epinician Odes. The Nonesuch Press has given permission for it to be reproduced in this way, and though Professor Wade-Gery has not been able to collaborate in new translations, he has willingly given permission for the republication of the Pythian Odes, in all of which he had a large share. So the Pythian Odes are here printed, with very few and small exceptions, as they were in 1928.

The others are my own work, made over a period of years. Considerations of space have discouraged me from reprinting the original introductions, but as Pindar is notoriously difficult to understand, I have added a few notes of explanation to each poem. I am not convinced that they are adequate, but I hope that they will give some help. I have also added at the end of the book a register of names to assist in deciphering Pindars allusive methods of nomenclature. I have confined myself to the complete odes and not made any attempt to translate the fragments. I have arranged the poems in what seems to me a likely chronological order, as this may help to illustrate Pindars development, but I am conscious that much in it is uncertain.

I have followed the text of my own Pindari Carmina in the Oxford Classical Texts, and in the very few places where I have diverged from it, I record the fact in a note. In my translation I have followed the method of the earlier book and made no attempt to keep either Pindars metres, which cannot be reproduced in English, or his formality of structure. I have tried to maintain a kind of free verse, but I have aimed much more at preserving the meaning of the original than its rhythm. I have not made my lines correspond with Pindars, and the numbers in the margin refer to the Greek original and not to the English translation. I have put them in since, even with this defect, I hope that they will make it easier to look up references. , who has read my text with generous care and made many wise suggestions. , who has read my text with generous care and made many wise suggestions.

For the many faults that remain I must myself bear the responsibility. C.M.B.

Main Events in the Games

Chariot-race [20] The chariots were four-horsed. The course was twelve double laps, nearly nine miles. Accidents were frequent. , it survived when forty crashed.

Mule-car race [25] This was introduced at Olympia early in the fifth century B.C. but discontinued in 444 B.C.

Horse-race The course was one lap of six stades, about 1,200 yards.

Horse-race The course was one lap of six stades, about 1,200 yards.

The jockeys rode without saddles or stirrups. Foot-race [30] This was from one end of the stadium to the other, about 200 yards. Double foot-race [35] This was from one end of the stadium to the other, and then back, in all about 400 yards. Long foot-race This varied at different places, but at Olympia was about three miles. Race in armour This was introduced towards the end of the sixth century. Wrestling The normal aim was to throw your opponent on the ground. Wrestling The normal aim was to throw your opponent on the ground.

A fall on the back or shoulders or hip counted as a fair throw. Three clean throws were needed for victory. Boxing There were no regular rounds, and no confined ring. The fight was to the finish, with either a knock-out or an admission of defeat. There was no rule against hitting a man when down. Five Events The pentathlon was a combined competition in running, jumping (long jump only), throwing the discus, throwing the javelin, and wrestling. Trial of strength The pankration was a competition in boxing and wrestling combined with kicking, strangling, and twisting. Trial of strength The pankration was a competition in boxing and wrestling combined with kicking, strangling, and twisting.

Biting and gouging were forbidden, but most other manoeuvres were not. You might kick your opponent in the belly, twist his foot out of its socket, or break his fingers. All neck-holds were allowed, a favourite being the ladder-grip in which you climbed your opponents back, wound your legs round his belly, and your arms round his neck.