For my brother, Gavin Lee.

They represented the elite, and today they were going to face the public, which had devoured tales of their heroics in the nations newspapers but had yet to put a face or name to the stories of incredible survival and battlefield triumphs.

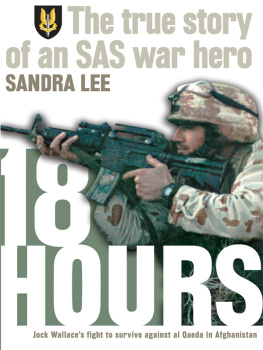

A RMY S IGNALMAN M ARTIN W ALLACE didnt feel much like a modern-day war hero. If anything, he felt slightly awkward as he stood on the perfectly manicured deep-green grass outside Government House in Canberra; conspicuous for all the wrong reasons. Wallace, a member of the Australian Armys elite Special Air Service Regiment, had been called to the nations capital where, in a few minutes, he would receive the prestigious Medal for Gallantry, one of the nations highest decorations for bravery in perilous circumstances. Wallace had earned it one hellish day nearly nine months earlier while serving his country in the War on Terror in Afghanistan. He had been fighting the remnants of the religious fundamentalist Taliban regime and their terrorist partners, al Qaeda, after the murderous September 11 attacks in the United States.

Their Excellencies, the Governor-General, Peter Hollingworth, and his wife, Mrs Ann Hollingworth, had issued official white invitations, stamped with King Edwards golden crown atop a sprig of wattle, to the investiture. Proceedings would commence at 10.50am and conclude exactly 70 minutes later at noon, sharp, on 27 November 2002. The dress code on that sultry Wednesday morning was appropriate to the occasion service dress ceremonial and accoutrements. Signalman Wallace was proud to wear the Australian Armys uniform, and proud of being a soldier in 152 Signal Squadron at the SAS base in Swanbourne, Perth, but the dress code had presented a slight and oddly amusing problem for him.

Despite being the star of the mornings pageant of pomp and ceremony, and despite his impressively chiselled good looks and ramrod-straight posture born of years of military service and parade ground marches, he felt like an impostor. While his lean, athletic physique gave it a definite and dignified authority, most of the all-khaki ceremonial uniform he was wearing had been borrowed, hastily. It came from his fellow soldiers in the Special Forces crew that lives by the credo Who Dares Wins. Wallace appreciated the irony, and had a laugh at his own expense: he was a member of the most elite and highly organised regiment, renowned for its adaptability in any environment, and here he was decked out in an improvised uniform. Bloody perfect , he thought.

The uniform he wore belonged to his troop commander at 152 Signal Squadron, a top bloke called Marty whom Wallace respected and admired. The shoulders had had to be widened slightly to accommodate Wallaces build, and the badges changed to recognise his rank. Wallace had borrowed the gold buttons for the jacket from a corporal within the SAS Regiments 1st Squadron, an old mate named Mick. They had served together on their first overseas mission twelve years earlier, and like Wallace, Mick had also served in Afghanistan. The wide black leather belt and brass had come from a fellow signaller at 152, another chook, as signallers are known, who had also completed a rugged tour of duty in Afghanistan in the early days of the War on Terror.

It was all a bit of a laugh, but what did irk Wallace later after the ceremony was that he was asked to remove his royal-blue beret for the official photographs thereby robbing his Royal Australian Corps of Signals of the honour he felt they deserved at this proud occasion. I felt like an op-shop dude going up to get an award in a borrowed suit and tie, Wallace remarked later, humour mixed with a small measure of embarrassment. At least he wore his own corps blue-coloured lanyard over his right arm, clearly identifying himself as a member of 152, something he would toast privately with his best mate and fellow SAS trooper, Mooka, over a beer after the ceremony.

But Wallaces awkwardness went beyond the borrowed uniform, and if truth be told, he focused on the uniform to conceal the real cause of his discomfort. His awkwardness was deeply entrenched in that rare characteristic possessed by brave men and women who would prefer not to be singled out for simply doing their job, no matter how extraordinary and courageous their actions have been. His reticence was rooted firmly in something that could only be described as the humility of heroes; he felt uncomfortable that the ceremony about to unfold would spotlight him and celebrate his gallantry and courage under fire. Soldiering is about mateship and teamwork.

There was something else, too. Martin Wallace or Jock, as he automatically became known, thanks to his Scottish ancestry, when he signed up as a seventeen-year-old in 1987 also felt sorely the absence of another brave Australian who was with him the day all hell broke loose in the largest combat operation in the War on Terror, and the biggest to involve Australians since the Vietnam War.

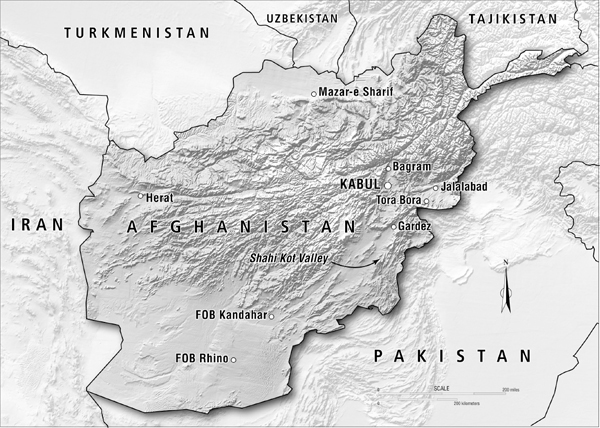

It was 2 March 2002, in a freezing place called the Shahi Kot Valley high in the Afghanistan mountains, where the air is so thin its hard to breathe. Of historical significance and breathtakingly beautiful, the area was the last stronghold of the multi-national terrorist group al Qaeda, and American intelligence had placed its Saudi leader, Osama bin Laden, in the region. Warrant Officer Class Two Clint was right beside Jock for most of the eighteen hours they were in the valley, pinned down after being ambushed by an estimated thousand al Qaeda terrorists and Taliban fighters. Clint and Jock fought for their lives and those of 80 soldiers from the US Armys 10th Mountain Division who had been deposited there that morning by three fully loaded CH-47 Chinook helicopters. If Wallace had his druthers, his brother in arms Clint would be standing right beside him again now, being similarly honoured. Instead, Clint was hard at work, having been overlooked for any award, something Wallace thought was wrong.

Wallace couldnt pinpoint the exact emotion he felt but the ceremony seemed somehow superficial, a bit hollow. A bit of a show, put on more for others than for him. The dangerous work had already been done, and yet more was needed back in Afghanistan. As a soldier, Jock wanted nothing more than to get back to the business, but he also knew the medal ceremony was bigger than him, bigger than one man who had done his duty. Its about the nation and about being Australian , he thought to himself as he surveyed the smartly dressed politicians and dignitaries who had come to salute Jock and the other soldiers who were being honoured.

Wallace was in good company. With him were the tough-as-nails commander of the regiments 1st Squadron, Major Daniel McDaniel, and his squadron sergeant, Warrant Officer Class Two Mark Keily. Both were superior officers in the SAS who, with Wallace, took part in what the Australian Defence Force called Operation Slipper as part of the American-led coalitions Operation Enduring Freedom. The three soldiers had notched up several decades of military service between them and had seen action in various countries on several continents. They represented the elite, and today they were going to face the public, which had devoured tales of their heroics in the nations newspapers but had yet to put a face or a name to the stories of incredible survival and battlefield triumphs.