Contents

DEDICATION

Spc. Marc A. Anderson, 30, Company A, 1st Battalion, 75th Ranger Regiment, Brandon, Florida; Bronze Star with V Device, Purple Heart

Tech. Sgt. John A. Chapman, 36, 24th Special Tactics Squadron, Waco, Texas; Air Force Cross, Purple Heart

Cpl. Matthew A. Commons, 21, Company A, 1st Battalion, 75th Ranger Regiment, Boulder City, Nevada; Bronze Star with V Device, Purple Heart

Sgt. Bradley S. Crose, 27, Company A, 1st Battalion, 75th Ranger Regiment, Orange Park, Florida; Bronze Star with V Device, Purple Heart

Senior Airman Jason D. Cunningham, 26, 38th Rescue Squadron, Camarillo, California; Air Force Cross, Purple Heart

Petty Officer 1st Class Neil C. Roberts, 32, Naval Special Warfare Development Group, Woodland, California; Silver Star, Purple Heart

Sgt. Philip J. Svitak, 31, Company A, 2nd Battalion, 160th Special Operations Aviation Regiment, Neosho, Missouri; Bronze Star with V Device, Purple Heart

Sic itur ad astra

These men went into battle with the comfort of knowing that should they die, their children, of whom there are eight, would have their college educations paid for, when the time came. The Special Operations Warriors Foundation was set up more than twenty years ago to provide this support, based on need, to the children of Special Operations personnel who are killed in operational missions or training accidents. Today, more than five hundred children are eligible, with nearly one hundred of them receiving assistance between 2003 and 2010; the Foundation's estimated financial need through 2010 is $34 million. The author is contributing a portion of the proceeds of this book to the foundation, which can be reached for tax-deductible contributions at: SPECIAL OPERATIONS WARRIORS FOUNDATION, P.O. Box 14385, Tampa, FL 33690.

I wouldnt leave you and you wouldnt leave me. That aint no argument.

Cormac McCarthy, All the Pretty Horses

I'm not trying to be a hero. If you think I like this, you're crazy.

Will Kane (Gary Cooper) in High Noon

A NOTE TO THE READER

The following story is true. It takes place over 17 hours.

PROLOGUE

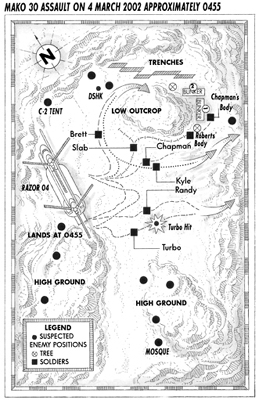

U NDER A SINGLE LIGHT THAT HUNG ON A CORD from a low ceiling of cedar beams and hardened mud, the U.S. Navy SEAL whom everyone called just Slab was leaning on his arms over maps spread out on a table. A good-looking, slim, blond-haired thirty-three-year-old whom strangers often mistook for the hockey legend Wayne Gretzky, Slab was planning how best his sniper reconnaissance team could help regular Army troops who were taking a shellacking from a large al-Qaeda and Taliban force.

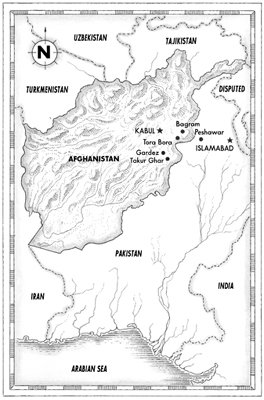

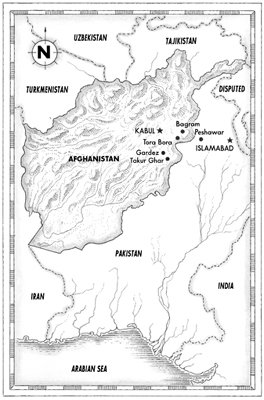

The sound of a gas generator blew through a window. It was cold enough for Slab to see his breath in this room of a dilapidated mud fort near the Afghan provincial capital of Gardez. Slab and his team had shuttled down from Bagram Air Base that morning by helicopter to see how they could salvage the largest offensive yet in the war on terrorismone that had collapsed only ten minutes after it began. Making the debacle doubly painful, Army commanders had initiated Operation Anaconda, as it was called, presumably to recoup the opportunities that were squandered earlier at Tora Bora, where hundreds of al-Qaeda fighters, including Osama bin Laden and possibly his chief lieutenant, Ayman al-Zawahiri, had all but waltzed across the border of Afghanistan into the sanctuaries of Pakistan's tribal areas. Many Chechens and Uzbeks among these hardened terrorists later had made their way south to this valley, called the Shah-i-Kot.

The original plan for Anaconda had called for the use of American and friendly Afghan troops to hammer Taliban and al-Qaeda forces, known to have regrouped in the valley in force for the winter, into a steep wall of high mountains. American troops would serve as the blocking anvil against which the routed enemy would be crushed, in theory. But the hammer never swung; it fled from the battlefield under lethal friendly fire from a U.S. gunship, from a shocked reaction to a softening-up bombardment that fizzled, and by ferocious mortar attacks by an enemy that was not going to be easily routed anywhere, much to nearly everyone's surprise.

The enemy fighters weren't as much in the valley, as imagined, as they were in the mountains looking down on the Americans through the sights of heavy machine guns and mortars. Making this already bad situation even worse, the highest American commanders had failed to equip elements from the 10th Mountain and 101st Airborne divisions with artillery with which to defend themselves. Bombers and strike aircraft assumed that role, which in turn required hastily placed special operatorssome, like Slab, on loan from the secret black world of the Joint Special Operations Commandto provide aircraft with targets and coordinates.

At the moment, with Slab studying maps, the fight was ragged and tentative, and the Army troops might not be able to hold out. As a sign of the crisis, commanders were even debating whether to pull back and call off the operation altogether.

Slab and his team were only seven mensix SEALs and an Air Force combat controller. It might have seemed preposterous to believe that they alone could change the course of an entire battle involving 1,400 American troops. They couldn't, not alone, but at their fingertips they commanded an endless supply of 2,000-pound high-explosive bombs, guided by tiny navigation systems that could slam targets from on high within yards of where they were intended. All the SEALs required for the job was a radio, a good high site with a view of the valley, and a snug place to hide.

The highest mountain overlooking the valley on the maps was called Takur Ghar, which translated as Tall Mountain from Pushto. Takur Ghar was chosen for Slab as an observation post, as one of his commanders told him, because of its superbly strategic position. Intelligence reports that he had read informed him that the enemy was being resupplied with munitions and reinforcements down ratlines through the biggest hole in the area of Takur Ghar.

It dawned on Slab that if Takur Ghar would be advantageous to the Americans, why wouldn't it also be appealing to the enemy fighters? After all, the local Taliban hardly needed satellites and computers to realize the advantages of mountains that they already knew as well as the faces of their children. Slab studied satellite imagery that by now was three days old. No snow showed on the peak in these pictures. He saw an old trench on the mountain peak that he assumed local fighters had occupied at one time, probably long ago. He did not plan to drop right down on the peak, in the unlikely event that an enemy force already occupied it. He'd land on an offset below the summit and then patrol up the steep mountainside. He was aiming that night literally to scope out the peak, which the team would take over once they were reassured of its vacancy through quiet observation. His job was not to make contact with the enemy; it was to stay out of reach and drop massive amounts of ordnance.

Next page