Contents

Guide

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

FOR THE PJS WHO HAVE COME BEFORE AND THOSE THAT WILL FOLLOW ME, AND FOR THE FAMILIES THAT LOVE AND SUPPORT THEM.

Im struggling to come up with right words of gratitude for everyone who has been part of this project and my life. I never thought the story of my life and adventures would be book-worthy, but I love being wrong.

Most importantly, I would like to thank my family. My mother and grandmother have been inspirations in fortitude and perseverance, as well as patience and love.

I wouldnt have been able to get beyond page one without the love and support of my wife. She took care of my son, the home front, and gave me the strength to complete this challenge.

I am grateful for the folks at St. Martins for believing in our project. Our editor, Marc Resnick, was a huge help, and I appreciated how he made the whole process unintimidating and positive.

Thank you, Adam Chromy, for breathing fire into our project and giving it life.

This book could not have happened without the tenacity and vision of Don Rearden. Don worked his way through my stories, then refined and tailored them into a smooth, flowing, and exciting book. Don took extra steps above and beyond what anyone could have expected. Thanks to Annette for supporting and cheering for us both, and thank you, Don, for your sacrifices and sleepless nights.

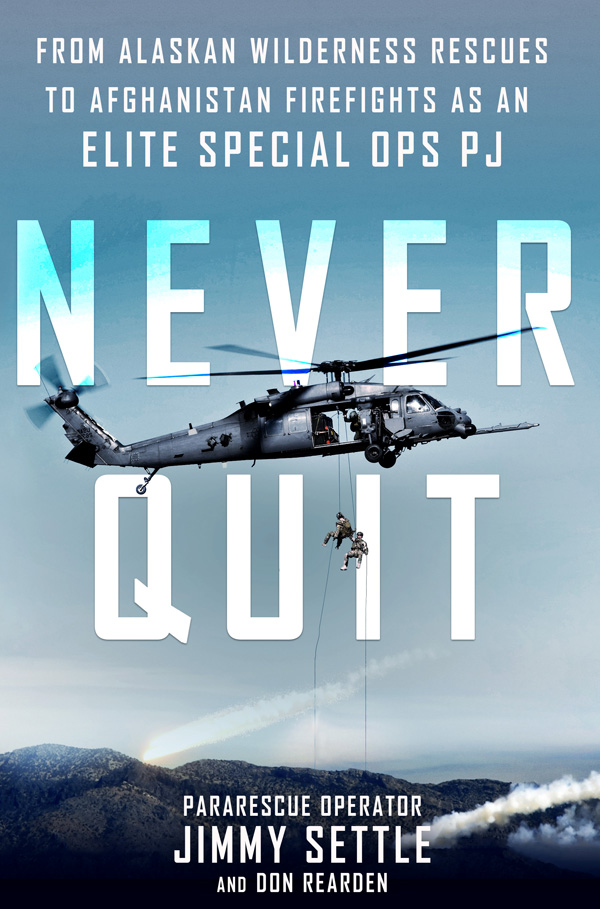

Speaking of sleepless nights, I would like to thank the entire brotherhood of pararescuemen and their crews. Their selfless dedication has saved thousands of lives around the world. Right now, there is probably a rescue mission going on somewhere. The path of the PJ is not easy. I had many great PJs guide and inspire me along the way. I lived an intense but brief life as a PJ, and I was surrounded by dudes who had been operating for decades. Those men have incredible rescue stories I hope get heard. If you see these guys on the street, buy them a time-appropriate drink and ask for a story. Even a boring PJ has cool stories. Im proof.

The lifestyle of a PJ is rewarding, adventurous, and dangerous. PJs are masters of risk mitigation, but sometimes the unforeseeable shows up and disasters happen. Many PJs perish each year on duty. Many more are permanently injured. These men are evidence of the creed all PJs swear to, which ends with That others may live.

The process of capturing my life on paper has been therapeutic. Some of the events I experienced have had lasting results, both physically and mentally. When Don approached me about doing this project, it was a choice I took seriously. I wanted to make sure I honored the people in my life and inspired readers to stay positive and hang on through tough times. Remember this: when life is throwing some INDOC-style hate at you, stay cool, and never quit !

Hooyah!

JIMMY SETTLE

Im already sweating my balls off! I yelled to Roger. Are you? What are you wearing under there?

Everything! he hollered back at me.

With my index fingers, I pushed the puffy foam plugs deep into my ear canals until the sound of the chopper spinning up became a muted background roar. I tugged at the rubber noose around my throat, trying to give myself a little more breathing room against the dry suits choking neck gasket.

I had to dig deep to find a reason to be excited about this training operation as the HH-60G Pave Hawks rotors picked up speed. My concerns werent really a premonition, just the nagging reality that the evenings duty would be one thing: cold. January. Minus twenty. In Alaska. The imminent danger of freezing to death in the Arctic waters of this training exercise wasnt the issue at all. Danger isnt in the job description of Alaska pararescuemen, or PJs, as were known. Danger is the job description. For PJs, danger is a dinner bell, and our day-to-day training reflects the situations of extreme danger and chaos we face during rescues at home or in battle abroad. Many pararescue operators have been killed during training, but that level of training is necessary to prepare for the worst-case scenarios inherent in the job. When the world goes sideways, you want the men coming to rescue you to be coolbut not necessarily the type of cool my partner Roger Sparks and I were about to face.

The familiar pressure of takeoff pushed me back into the cold vibrating floor of the helo. Anchorage dropped away beneath us, and the glow of the city, covered in a heavy blanket of January snow, disappeared.

Cold. Nighttime. Water work.

No one willingly jumps into an ice-choked ocean in Alaska at night when the ambient temperature is pushing twenty below. At least, not anyone in his right mind. Yet, there we were. Two choppers hurtling out into the black night sky toward nothing but possible trouble.

If we were operators from the Florida team, nighttime water work would be no problem, maybe fun. Those men do their water work in stylish beach trunks and surf shirts. But for the PJs of the 212th a routine water jump could potentially mean life or death. Alaskan water, even in the middle of summer, is no joke, and this is a fact Ive known since birth. Alaskas frigid waters have not been kind to my family.

In general, water work was never my favorite pastime. It really wasnt. I didnt mind training for rescues in our bone-chilling waters in the summertime, or even the occasional daylight splash drill in the winter. But water rescue, even at night, is something I was expected to do. The willingness to scuba dive, parachute, or swim at all hours of the day was my job as a PJ. Anywhere off of Alaskas forty-nine thousand miles of coastline, or in our three million lakes or twelve thousand rivers, was fair game and represented a possible rescue location.

Its not as if I could say, Oh, sorry, chaps. I dont do water rescues at night. When command says youre doing night work, then that is it. You saddle up.

The situation Roger and I were flying into was designed to be nighttime tactical water work. We werent training for a civilian rescue of the sort we normally saw in the waters around Alaska. We had our gray tactical suits on. No reflective material anywhere. This was all covert stuff. Something youd see in a thriller. Everything black. Dark IR strobes, only visible with infrared scopes. Not so much as a light flashing on the chopper.

We raced low over Cook Inlet, the only illumination coming from the glow of Anchorage as it slipped away behind us, reflecting off the hulking white pans of ice that flowed in the ripping tidal currents.

Two minutes out, they signaled to us that we were a few clicks from the drop zone. Roger and I began our routine checks of each other and ourselves. Doing water work in Alaska, you must wear the dry suits, because wet suits wont do the trick. The water is just too cold. We wore specially made survival dry suitsand they are a real pain in the ass to climb into. The suits have two heavy rubberized zippers and painfully tight rubber gaskets at the wrists and neck. The smell of the rubber gaskets always reminded me of bicycle inner tubes. Imagine tying a rubber noose around your neck and then having the strongest person you know wrenching on the business end, and youve got an idea of the strangling effect. To ease the constant choking sensation, we rigged up neck rings. This simple little device closes in around the neck so the thick, death-gripping gasket rolls down off your Adams apple and windpipe. This provided a little respite and kept us from being purple-faced and choking to death the whole time en route.