Table of Contents

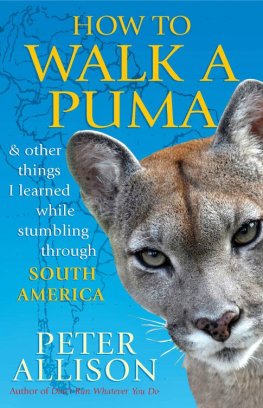

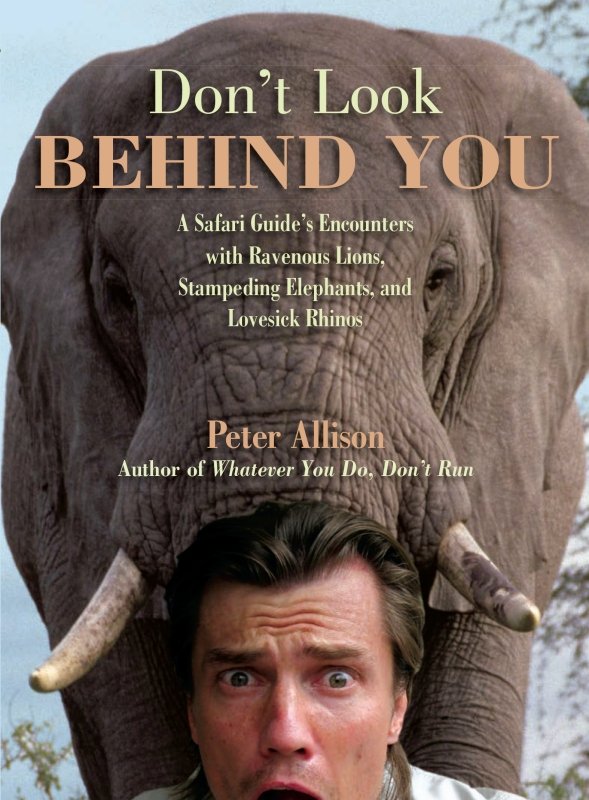

ALSO BY PETER ALLISON

Whatever You Do, Dont Run: True Tales of a Botswana Safari Guide

This book is again dedicated to anyone who works to preserve wild placesfrom those who live in uncomfortable conditions in the field to teach us more about animals, to people who take a little time to lobby for protection of wilderness, my good friends in the safari business, and even the legislators who sign national parks into existence. They all make some sacrifice for this, and I salute them.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This list must always start with Flavia, whose patience and love give me a foundation that I can work from. Not many people would tolerate hearing these stories a hundred times and then endure reading them, but she does just that with good humor and many servings of pasta.

My hardworking agent Kate Epstein takes care of so many things that I am no good at, but beyond that is also a great friend and mentor.

Holly Rubino at The Globe Pequot Press was sent a rather drab first draft and patiently guided me toward what you hold here, for which I am very grateful and hope you will be too.

This book was not written in any one placesome in my home in Sydney, but much while I was on the road. Many people had me in their homes at this point, and I must thank Attie and Christina Jonkerhosts so generous and kind I suggest you track them down and befriend them, then stay at their place; you wont want to leave. Iva Spitzer saved me from the bankruptcy that staying in New York would have brought about, and did it in great style while we swapped many an African story. Devlin Foxcroft showed that despite his many bad habits (really, who drinks beer from a shoe?) he is a great friend to have and put me up in Johannesburg. Thanks also to Alta from his office at Impulse Getaways for arranging so much.

The people in the 5 x 5 social room (you know who you are) gave me a welcome distraction when I was blocked, but just as often when I should have been working. Any mistakes I missed during the edits can be squarely blamed on them.

Lastly, Ive had family support not just from my wonderful sister Laurie, but also from Susie and the late Renzo Abbate. We all miss you, Renzo.

INTRODUCTION

Writing is a dangerous game.

In 2007 I wrote a book called Whatever You Do, Dont Run. Seeing it published gave me a triple thrill. It made me a fourthgeneration writer on my mothers side, it fulfilled a lifelong ambition to become an author, and lastly but not of least significance, it put some money in my pocket. The check sent to me was for an amount meager to most, but able to cover my rent for some time.

When I went to deposit the check at a suburban bank branch in Sydney, the teller smiled back at me in the professional way that bank tellers do. But as she studied the check, the faade began to crack a little, and then crumble. I just stood there, grinning broadly, unaware that she was reaching for the silent alarm.

My fiance, standing beside me, was far sharper, and leaned forward. Its the title of a book, she said softly. This is his first payment as a writer.

I took a while to register what Flavia had said, and to interpret the look of horror that was now fading to vague suspicion on the face of the cashier.

Oh! I said, then Oh! again, just to demonstrate how articulate writers are, realizing that the book title was printed on the check. Dont Run! Thats not a good thing to hand over in a bank, is it?

I wasnt arrested that day, but it was close. If Id been by myself, I just may well have been.

So being a writer has its hazards, ones that most days I dont seem prepared for. Being a safari guide was not dissimilar. I started each day knowing that I might find a scorpion in my boot, get lost in the bush, or be charged by a lion. While I am not at all a brave man, I am fascinated by animals, and my curiosity about what might be around the next corner or what Id see next kept me in the game for more than ten years. The stories in this book are campfire tales, the sort that safari guides tell at night, but there are also a few confessions that would never be shared with tourists.

This is not a sequel, but rather a companion volume to Whatever You Do, Dont Run. It starts at the start like a story should, at the beginning of my career, and hops through various stages of training, guiding, camp management, and teaching. My career began in the Sabi Sands Game Reserve of South Africa, a private section of the famous Kruger National Park. From South Africa I moved to the place that became my home, Botswanas Okavango Delta. For most of my time there I lived at a place called Mombo, an island in the middle of the worlds largest oasis, which sits in the middle of the worlds greatest stretch of sand. This is a place where desert animals from the Kalahari make their homes next to aquatic creatures like hippos, and where the unusual becomes commonplace. In the Delta it is possible to see some of the larger cats swimming for fun, herds of buffalo that shake the land, and a flood that comes in the middle of the dry season. There is no place like it on Earth.

These are the stories of a not particularly brave safari guide.

THREE LITTLE PIGS

I was at the bottom, looking up. Above me were safari guides, offering encouragement, telling me it was easy to get where they were. But I am a lifelong fearer of heights, to the point that I dont even enjoy standing up, and think it far more sensible to stay seated. The guides shouted out to me that I was missing out on a great view, and that they could see all sorts of wildlife and scenery from their perch on our brand-new communications tower. I wanted to join them, wanted to defeat my phobia, but after repeated failure, I could only tuck my tail between my legs and slink away.

Once the others were gone I returned to the tower and made another solo attempt. I was very proud to be three rungs higher than I had gone previously, above my own head height. My hand reached for the next rung, but instead of feeling metal I gripped something slimy. It squirmed. My hand released its hold, and for no good reason the other one did too and I fell, with just enough time to think tree frog before my feet hit the ground, skidded out, and my backside gave a flat thwack into the hard packed earth. The frog was nowhere to be seen, presumably still safe on its perch wondering why the purple-faced and sweaty creature that had grabbed it was so quick to let it go.

I looked back up the tower, wondering if I should try again, mustering courage. But just the sight of its distant tip made the sky turn, and I gave up. On this casually violent continent I was more afraid of this tower than I was of any man or animal.

Bugger it, I said to myself, shot a last resentful glance skywards, and limped away.

Three days later I was there to greet the safari vehicles as they came in from their morning drive. This was a task that was starting to gall me. Id been training to be a guide for months, and was achingly close to my goal. Serving drinks in my role as camp bartender, never an imposition before, felt beneath me now. I yearned to be given the credibility of the neat khaki shirt and embossed epaulettes of the guides, bolstered by the machismo of driving with a rifle in front of me and the real ability to muscle the chunky four-wheel-drives around the bush. Instead I listened to Devlin as he hopped from his vehicle and announced that there were lions just outside the camp, and that I might want to warn the rest of the staff not to go past the outskirts of the structures that made up our enclave of civilization.

Next page