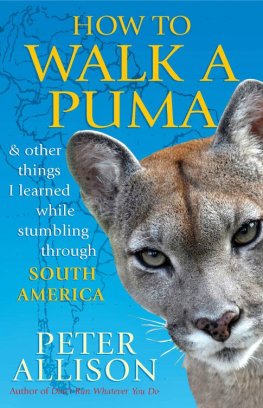

Peter Allison

THE LYONS PRESS

Guilford, Connecticut

An imprint of The Globe Pequot Press

Copyright 2008 by Peter Allison

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, except as may be expressly permitted in writing from the publisher. Requests for permission should be addressed to The Globe Pequot Press, Attn: Rights and Permissions Department, P.O. Box 480, Guilford, CT 06437.

The Lyons Press is an imprint of The Globe Pequot Press.

All photos are by the author unless otherwise noted.

Text design by Lisa Reneson

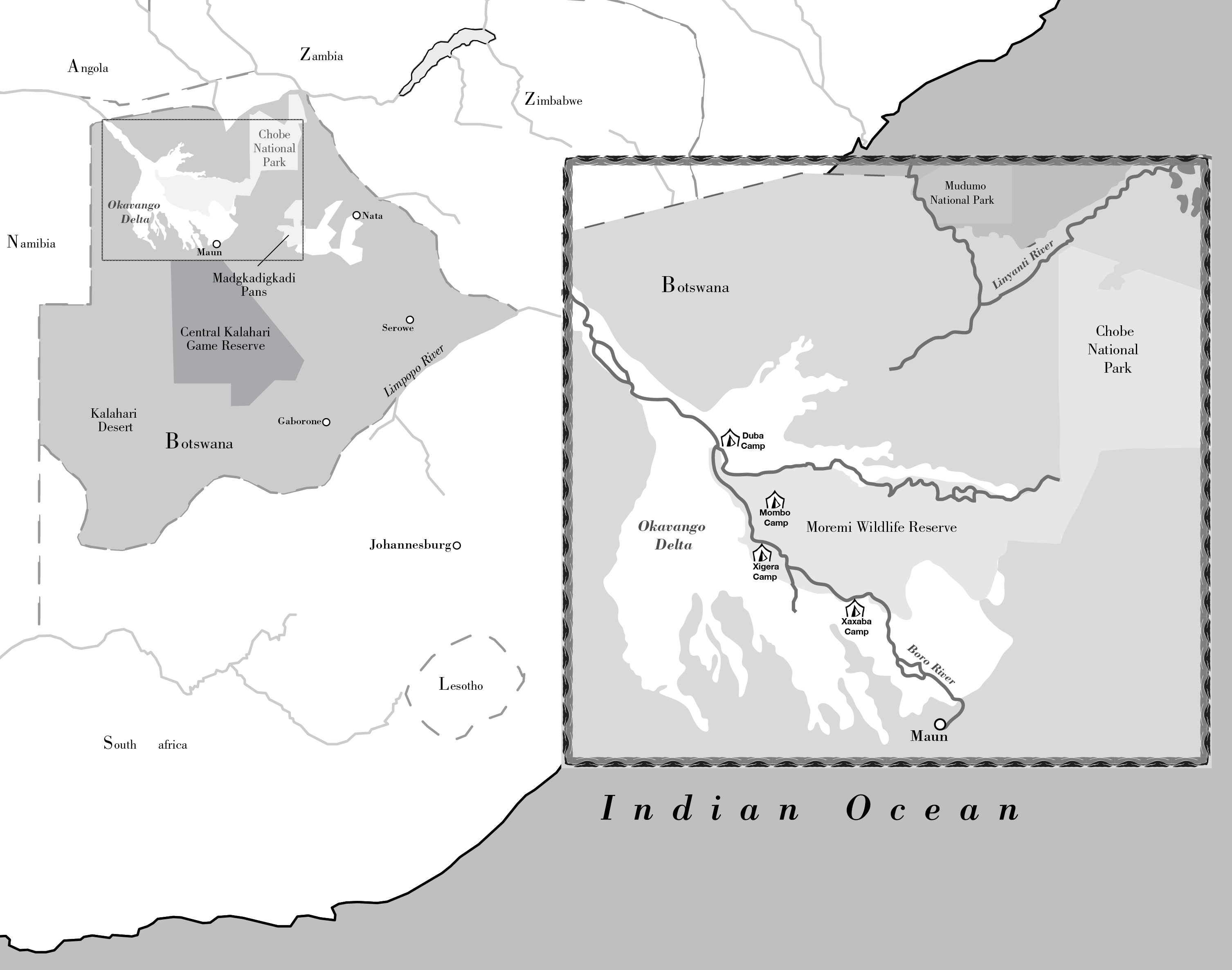

Map created by Lisa Reneson Morris Book Publishing, LLC

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Allison, Peter.

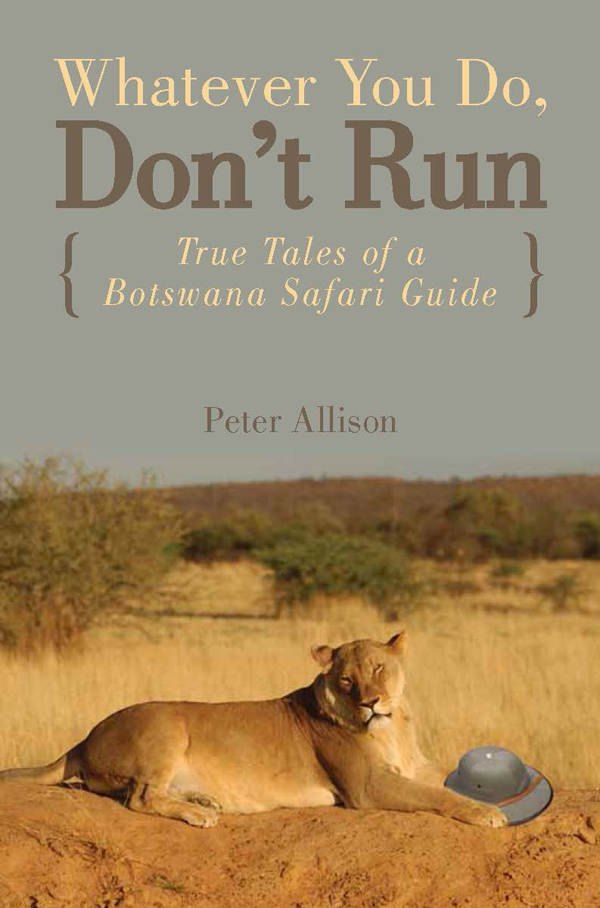

Whatever you do, dont run : true tales of a Botswana safari guide / Peter Allison. 1st ed.

p. cm.

E-ISBN: 978-0-7627-9605-2

1. Allison, Peter. 2. Safari guidesBotswanaBiography. 3. SafarisBotswanaAnecdotes. I. Title.

G156.A45 2007

916.8830432092dc22

[B]

2007005094

This book is dedicated to anyone who works to protect wild places and the animals within them, but in particular to the safari guides who taught me so much.

My particular thanks go to Chris Greathead, Devlin Foxcroft, Iain Garrett, the Marais family (including Sally), Helen Dewar, Duncan Menzies, Alpheus Mathebula, Titus Indloovu, B.K. Setlabosha, Lloyd Camp, Clinton Cliffy Phillips, Grant Woodrow, Mike Myers, Lex Hes, Richard Field, Paul Allen, Colin Bell, Russell Friedman, Chris Kruger, Julius Masogo, the late great Rantaung Rantaung, and the sadly missed Nandi Retiyo.

Everything I know about animals I learned from this group, so any mistakes in this book are their fault.

Contents

Acknowledgments

This book couldnt have been written without the able assistance and encouragement of a wonderful group of women. Without Flavia I would never have had the courage to start this book, let alone finish it. My sister Laurie was subjected to some of the earliest drafts without visibly wincing. Without my magnificent agent and friend, Kate, I would never have found a home for the book and met Laura, Imee, Gail, Jaclyn, and Katie at Globe Pequot. To all of you I give many, many thanks.

Introduction

When I was nineteen, after two years in a job that was going nowhere, I bought a ticket and set off for Africa. I went for two reasons. First, I wanted a challenge. And second, all of my life I have loved and been fascinated by wildlife. My plan was to stay for only a year.

After six months of backpacking in Africa, I had spent most of my money and the rest had been stolen at a Malawian campground. This helped fulfill the criteria of a challenge. Kindly fellow travelers offered to drive me to South Africa, where I could arrange for more funds. During our journey we stopped at a game reserve.

At the end of two astonishing days, which I spent in a state of euphoria, my obvious enthusiasm was rewarded with an offer to run the bar at the camp. Happily putting down my backpack, and cutting off my long hair, I accepted.

Living in the bush was more than I had ever expected was possible. I had grown up in the most sedate suburbs, and in my own mind I had none of the qualities you would expect of a rugged bush man. Im markedly uncoordinated, cant repair vehicles nor understand how they work, I dont like guns, and sweat profusely when nervous or excitedwhich is exactly how watching animals makes me feel.

Nevertheless over time I advanced in position and became a guide, then a camp manager, then a teacher for others who wished to become guides. My short holiday to Africa has been keeping me busy since 1994, and I dont foresee it ever ending.

These are the stories from the life of a safari guide.

Whatever You Do, Dont Run

The first place in Africa that employed me was a camp called Idube. The people who came there, like the people who came to every camp where I have ever worked, loved a thrill, something different. So we took them out to dinner.

Not far from our main camp we had a small setup, inventively called the Bush Camp. It included a teepee over a toilet and a clearing where a fire could be built. Around this, chairs and tables were set, ready for the delighted guests who would be brought in the dark for their meal. Firelight is romantic and makes everyone look beautiful, just as it did for the Bush Camp. With lanterns lit and a beaming staff, the place looked perfect. But during the day it was only a sorry patch of earth, and the teepee was filled with spiders. The guests loved it, and the nights were cheap for the camps owners, so they insisted we run them at least once a week.

The staff didnt like these dinner nights in the bush. Setting up meant that the usual quiet time, when all the guests were out of camp, was suddenly filled with frantic activity. The one spare Land Rover, a decrepit and spluttering machine called the Skorokoro (which means too old to work in Shangaan), would be loaded with firewood, lanterns, and a chef named Wusani, whose bulk always made the aging suspension creak ominously. Wusani particularly disliked these bush dinners, as one afternoon after being dropped off she was unpleasantly surprised. Shortly after she lit the cooking fire, a lion roared, according to her description, closer to me than a baby is to its mother. Lions often walked in the soft sand of the dry riverbed that flowed beside the Bush Camp, to enjoy the shade or maybe to startle an antelope that had been lulled to sleep by the cool and tranquility of the surrounds. This lion was not hunting, or it would not have roared, but that didnt make it any less terrifying for Wusani.

When the Skorokoro and its driver returned that day with the tables and chairs, they found Wusani improbably perched on the outermost branches of a long-dead tree. When told it was safe to come down, she would not, because she could not. Adrenaline had fueled the climb, and now she only had the strength to cling on and beg for a ladder that the camp did not possess.

Finally gravitys pull resolved the issue. Despite her substantial weight and the height she fell from, Wusani was saved from serious harmperhaps by her ample padding. But she would never stay at the Bush Camp by herself again, and she warned me against it when I started working at Idube.

My job for bush dinners was simpler than Wusanis. I had to transport sufficient amounts of alcohol to the Bush Camp to last the night. I hadnt been working at the camp long, and as barman I was probably the most lowly staff member after the gardener, who watered the lawns that the warthogs promptly dug up. This gave me last priority when it came to loading the Skorokoro.