RICHARD GRANT

ANOTHER GREEN WORLD

Richard Grant was born in Norfolk in 1952, attended the University of Virginia, and served in the U.S. Coast Guard. He lives in Rockport, Maine, where he has been a contributing editor of Down East magazine, chaired the literature panel of the Maine Arts Commission, and won a New England Journalism Award for his column in the Camden Herald.

ALSO BY RICHARD GRANT

Saraband of Lost Time

Rumors of Spring

Views from the Oldest House

Through the Heart

Tex and Molly in the Afterlife

In the Land of Winter

Kaspian Lost

When I look back today,

the image of a romantic

and also a cruel and ruthless world

rises before me.

Albert Speer

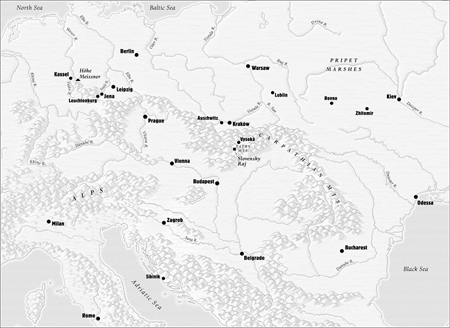

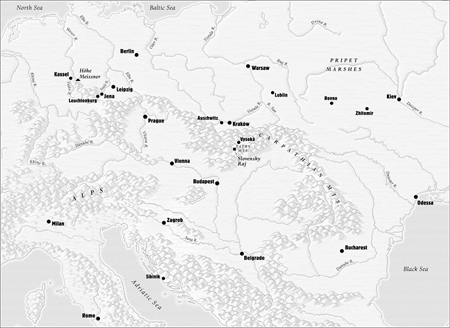

VYSOK, HIGH TATRY

MAY 1944

T he boy arrived nameless and barefoot. They reckoned he could get by without shoes a while longer, until a suitable pair could be stolen. But names, they had plenty of those, more names than people to wear them. So they began calling him Shlomo, or Solomon, because once there had been a Shlomo whom everybody had likedwhen he got killed in an ambush, they blew up a supply train in his honorand because the boy's lidless, owl-like stare gave him a look of preternatural wisdom. Nobody cared that he must have been called something else. The past meant nothing to these hungry, half-crazed heroes, and few of them expected to know a future. They were like birds shot in ight who would not survive the long, thrilling plummet to the ground.

Meanwhile there was a world to love: mountain lakes that shone black and bottomless like the eyes of a god; sunlight as hard as ice shards; slow-motion waterfalls; a tang of smoke in the upper air; pointed trees and naked, bronze-toned rock; and beyond, unrolling in yellow and green, the vast plain of Northern Europe, like a primed canvas on which generals painted their wars.

Nobody knew where the boy had come from, and he seemed unable to tell them. Certainly he had traveled far because his feet were bleeding from the journey. He was undersized, like everyone who had grown up in the ghettos and the camps, and might have been any age from eight to twenty. He stared at them and at the black spruces and the pitiless blue sky. His eyes drank the world in and gave nothing back. For all you could tell, he was blind. For all you could tell, he was gripped by visions, searing glimpses of eternity. Whatever the truth was, he was not disposed to share it.

He had come, they supposed, seeking the great man, the guerrilla chief, wily and stouthearted, who gave hope to what few of his people remained. The great ghter, so people said, struck at the niemcy, the dogsthat is, the Germanson roads and in forests and in their own well-patrolled lairs. He fought them by night and by daylight, using whatever weapons were available, including his own hands. He had never been beaten, never outsmarted, never caught. The more fervent members of his cult swore he had killed a man with his eyes alone. For years the niemcy had hunted him, snarling at his heels like a pack of ravening wolves, yet he had slipped out of their jaws. And still the contest dragged on, the ritual chase, even as hunters and hunted were together dying off.

How much of this legend the boy might have heard was beyond knowing. He sat patiently at the center of the camp, not too close to the re, not too far away, barely responding when people spoke to him, accepting what food they had to offer with no more than a nod of thanks. He ate like an animal, gnawing and grunting.

A week passed or morethere was little point keeping track, unless a rendezvous or a timed detonator was in questionbefore the great ghter returned from a mission deep into Poland. He came alone, slipping into the mountain hold so quietly that the sentries might as well have been asleep. Somehow, despite the dark, he noticed the boy straight off. He gave him a look that some described as thoughtful and others as distracted while moving quickly through the camp, summoning this one and that oneonly his closest deputies, those he had chosen to run things when he was absent and, in the course of things, deadand leading them to a small hut near a cold, whispering stream. Later it was said that a sheet of paper had been passed among them. Tallow light ickered briey and went out. The ghter's shadow fell once more by moonlight.

The boy did not inch and offered no greeting when the great man stepped closer to the campre, lowered himself before it and held his hands out, palms open, like a supplicant, or a prisoner demonstrating his harmlessness. He ignored the boy, or seemed to, though they sat barely a stride apart. The rest of the band looked on from a respectful distance, none wishing to disturb their weary leader or to interrupt the rapt observances of the hollow-eyed, wasted boy. They remembered meeting the great man themselves for the rst time, after everything one had heard. The surprise of ithow small he was, how physically insignicant: short-legged, long-necked, all joints and no muscle, perhaps even, though no one dared say it, the least bit stoop-shouldered. And that facewell. Could this truly be the famous warrior, hated and feared by the Nazis, whose deeds were celebrated around a thousand res in the outlands of Mitteleuropa?

Such thoughts might have run through the mind of the boy called Shlomo. Or they might not. His empty eyes betrayed nothing, only stared with a perfect equipoise known best to the already-dead. Then suddenly all who were there remembered such an instantthe great man turned to look at him.

The boy's eyes stretched even wider than before. But he didn't blink; bravely he met the terrible gaze that, so legend held, could kill you as surely as a bullet. Thus they remained, until the hero did something odd with his mouth, or his nose, maybe his earsyou couldn't say exactly whatand the boy responded just as they all had, each in turn.

High on a mountain in a land once called Czechoslovakia, claimed by at least three factions in this war that would go on forever, a boy who wore lightly the name of a king blinked his eyesthose eyes that had watched from the forest while his family was murdered one by one, little Mirka rst and Papi lastand with no warning at all, least of all to himself, he began to laugh.

His laughter was high and wild. There was relief in it and a kind of delirium. It rose like smoke on the chilling breeze, and before it faded, the great ghter had taken the boy into his arms and continued to hold him, wordless, as if the two of them had slipped out of the war, out of time itself.

And so in the dark heart of Europe, a lost boy tasted peace.

But what peace could there be for the ghter?

THE DISTRICT

JULY 1944

I ngo Miller, the man whose life she was about to ruin, ran a beer-and-schnitzel joint north of Dupont Circle. He lived in a at upstairs and, so far as anyone knew, rarely set foot off the premises. But this intelligence, like the rest of her private dossier on Miller, I., though extensive, might have been years out of date. So to make certainand, let's be honest, to buy a little more timeshe dispatched a pair of typists armed with a petty-cash disbursement on what some ofce wag promptly dubbed a Daring Mission Behind Republican Lines. Their report, presented three days later, was dishearteningly clear: Outside his restaurant, the subject had no life worth speaking of. He was making, it seemed, his last stand there, besieged on every side by the twentieth century. If she meant to play Red Death to his barricaded prince, that was the place to do it.