Table of Contents

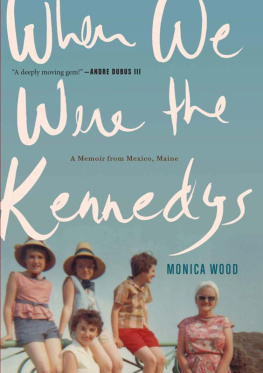

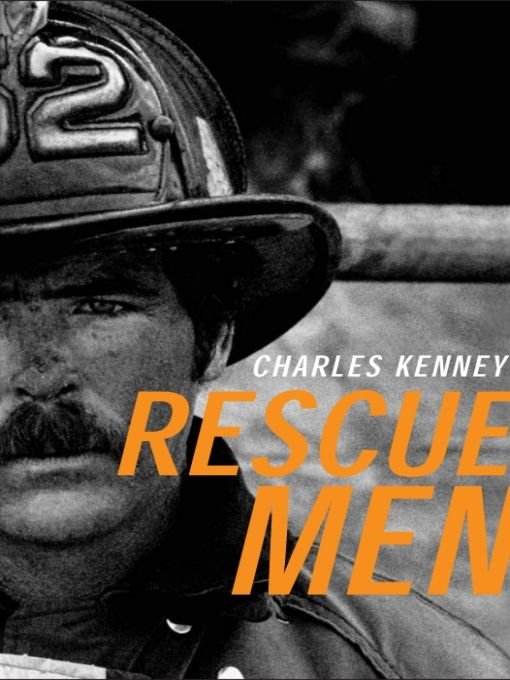

This book is dedicated to my brothers

Michael, Thomas, Patrick, John, and Timothy.

And, of course, to my father.

Withersoever Thou callest me, I am ready to go.

FROM A FIREFIGHTERS PRAYER TO SAINT FLORIAN

BY RICHARD CARDINAL CUSHING, ARCHBISHOP OF BOSTON

Preface: A Family Story

My father, nearing age eighty, sits surrounded by boxes of files, notes, audio- and videotapes, photographs, and transcripts. All of this and more has made him one of the worlds leading experts on the Cocoanut Grove nightclub fire of 1942. A couple of decades ago, my father set out to try to understand one of the worst fires in American history and eventually became intimately knowledgeable about an inferno that killed 492 people in minutes.

I was just a firefighter doing something as a hobby, he says offhandedly. I wanted to try and find out as much as I could.

My father was a rescue man on the Boston Fire Department. He followed in the footsteps of his father, who was also a rescue man and who had been at the Cocoanut Grove fire. In the process of research and investigation, my father gained an encyclopedic knowledge of the fire. He had never written a book, never written anything longer than a few pages, in fact, yet he had set himself the task of writing a history of the fire.

Now it is the winter of 2004, and we sit in his home in a small Cape Cod village. There is the quiet here of a summer place in the dead of winter. Sunlight slants through the sliding glass doors leading to the yard and my father sits with his boxes and files and notes and tapes, and he talks about the fire, as he has done since I was a child.

The first person I called was George Graney, he says, recalling that day in 1987 when his research began. He was at the Grove with my father. I called George at home in South Boston, Athens Street. He was long retired, I had not spoken with him in forty years. When I called, George said, I was just sitting here talking about your father. We were talking about the Cocoanut Grove and I was talking about how your father saved those people.

My dad recalls the conversation with a certain satisfaction, as though, yes, of course, when you call someone after forty years they would surely, at that very moment, be talking about your father and the fire at the Grove.

As part of the research he began in 1987, my fathernicknamed Sonnycalled the Boston fire commissioner, Leo Stapleton, who invited him to fire headquarters. As young men, Sonny and Leo had fought fires together, and the commissioner greeted him warmly. At the commissioners direction, an assistant led Sonny upstairs to the department files on the Grove, where he found tens of thousands of pages of documents buried away. To Sonny, the dusty files were a gift. He focused on the Form 5sofficial reports filed by each Boston Fire Department officer after a fire. Here was every detail: which companies arrived when, what they did, and the name of every firefighter on the scene. Sonny also found the transcript of the official department investigation into the firea hearing that had been convened less than twenty-four hours after the fire and had continued for weeks. Sonny found the testimony from hundreds of witnesses, twelve volumes of transcripts in all.

He went home and read through the Form 5s. He read them a second time and then a third, comparing them, studying them, committing many to memory. Then he read the twelve-volume transcript of the investigation and when he was done reading every word, he read it againthen again. Using this mass of information, he calculated that within just eight minutes on the night of the fire, twenty-five engine companies had arrived upon the scene.

Sonny and I sit together on this frigid winter day in 2004, the sun bright in the sky, and I listen as he tells stories of the Grove. Soon, the subject of his book comes up. He sits and draws on a Lucky Strike, letting the smoke gather in his lungs, then slowly, languidly releasing it, letting it drift upward, creating a cloud that rolls and rises slowly through the slanting sunshine. All of the reports, the testimony, everybody said that the fire did not behave as an ordinary fire, he muses. He had known that at the time, of course, from his own father. But this thought has stayed with him through the years, puzzling him, eventually haunting him. He turns his face toward the sun streaming in and says softly: The fire that got me didnt behave in a normal way, either.

The Cocoanut Grove fire defined our family in a way. It was, as Sonny once put it, the magnetic center of our attraction to firefighting. For Boston, the Grove was a moment in history and we were part of it, forever connected. My paternal grandfatherwho was known as Popswas with one of the first companies to arrive on the scene, and he was able to save numerous lives. Through the years, the legacy of the Grove has been passed down through three generations in our family. Pops was badly injured at the fire. Notwithstanding what happened to him, Sonny was drawn to follow in his footsteps. Later, to Sonnys eternal satisfaction, my brother Tom not only followed themthe third generation of Kenney rescue menbut proved to possess something of a genius for the work, engaging in a series of rescues through the years that would please Sonny as nothing else could.

When my father brings up the subject of the book he wants to write, I believe I know what is coming. For my father sits in the sunlight, enjoying his stubby, filterless cigarette, his white wavy hair pushed back, surrounded by his treasure trove of research and revelationsand he tells me that the book ... well, there is no book. We sit in silence for some time. I have questions I want to ask but I remain silent, hoping that he will reveal something to me. He is careful with his thoughts and emotions, even stingy at times. And soon, as I persevere in the increasingly brittle silence, he speaks.

There were so many interruptions, he says, frowning, trying to explain. There was Nanas illness, he says, referring to his mother, Molly. Theresas death, he sayshis second wife. Then he pauses and catches himself, shaking his head as though scolding himself.

Thats an excuse, he says. The truth is I didnt have the drive. I didnt have the discipline to do it. His words hang in the air. His jaw is fixed in a frown.

But I wonder whether there isnt more to it. I wonder whether, along the way, he saw inside of the history, saw the arc of a story that began and ended with the Grove but contained within it the story of our family. Perhaps he realized that to tell the story of the Cocoanut Grove in the context of his own family would require revealing history better left undisturbed. I wonder whether during his work he caught a glimpse of the story he would have to tell and flinchedthe story of how bedrock institutions, including the U.S. government in the form of the federal courts and the Roman Catholic Church, betrayed him and his family, leaving him confused, angry, and hurt. How would he write about the loss of his closest boyhood friend? His first wife? His father? How would he handle the loss of the only job he ever truly loved? The dark period where he lost his way and sought refuge in alcohol? How would he describe his fear when his son Tom was sent as a rescue man to Ground Zero on September 11, 2001?