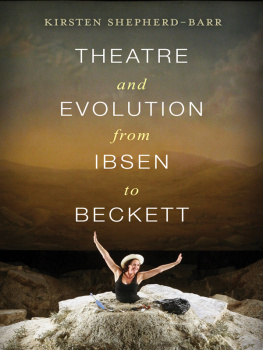

Ibsen

on Theatre

edited by

Frode Helland and Julie Holledge

with new translations of Henrik Ibsens writings by

May-Brit Akerholt

foreword by

Richard Eyre

NICK HERN BOOKS

London

www.nickhernbooks.co.uk

Contents

Foreword

I ve often felt that Id like to apologise to Ibsen. With the scant evidence of seeing a very poor production of The Wild Duck and a worse one of Rosmersholm and directing a misconceived production of The Master Builder in the late sixties, I used to share Chekhovs intemperate view of him: that he wasnt a playwright. He said that to Stanislavsky; to another friend he said Ibsens an idiot. He recoiledas I didfrom Ibsens apparent neatness, his use of symbols, of dialectic, of discussion. I was drawn to Chekhov because of his mordant wit and his worldliness: his dispassionate doctors eye. I favoured his talent for transforming experience of life and love into art. His characters seemed to exist entirely independently of their creator, whereas in my eyes Ibsens characters were inanimate tools of their maker. Forty years later I still retain a passion for Chekhovs writingthe stories as much as the playsbut now I regard Ibsen as very much his equal.

My view of Ibsen started to change when I directed John Gabriel Borkman with Paul Scofield, Vanessa Redgrave and Eileen Atkins at the National Theatre in the nineties. I discovered that you scalded your hand when you touched this icy playa sensation sustained during the whole two hours of its action. I thought it was like pouring liquid nitrogen. There is no point in painting winter after Ibsen has done that in John Gabriel Borkman, said Munch. But more surprising to me than its fierce chilliness, and its blistering vision of the future of capitalism, was that it ached with the need for love.

A few years later I directed Hedda Gabler and was capsized by the daring and the wit of it, the unexpected lack of solemnity, the defiance of an audiences expectations and the reluctance to conform to reductive theory. Is there any other dramatic heroine with such a confection of characteristics as Heddafeisty, droll and intelligent, yet fatally ignorant of the world and herself? Snobbish, mean-spirited, small-minded, conservative, cold, bored, vicious; sexually attractive but terrified of sex, ambitious to be bohemian but frightened of scandal, a desperate romantic fantasist but unable to sustain any loving relationship with anyone, including herself. And yet, in spite of all this, I was mesmerised by her; I was drawn to her; I pitied her.

Far from creating characters that appeared to exist solely in order to illustrate the playwrights ideas, Ibsen seemed to me to be doing much the same thing as Chekhov:

I realised quite late that to write means essentially to see, but, specifically, to see in such a way that what is seen is received just as the writer saw it. But only what is really lived through can be seen and received in this way. And the secret of the new literature of our time lies precisely in this relation to experience, the lived through. I have spiritually lived through everything I have written in the last ten years (see pp. 910).

Ghosts was the next of Ibsens plays that I directed. When he was working on the play he wrote this to a friend:

To me, each new piece of work has served the purpose of a spiritual liberation and cleansing process; for you are never without responsibility for, and are always complicit with, the society to which you belong. Therefore I once wrote the following lines as a dedication at the front of a copy of one of my books:

To live is to war with trolls

in the vault of the heart and the brain

To writethat is to hold

doomsday over oneself (see p. 49).

To hold doomsday over oneself means sitting in judgement on oneself, which is to say mediating ones ideas, emotions and anxieties through ones characters, who in their turn have to absorb the subject matter into their bloodstreamin the case of Ghosts: patriarchy, class, sex, hypocrisy, heredity, incest and euthanasia. In that sense Helene Alving, the protagonist of Ghosts, is as much an autobiographical portrait as Hedda: yearning for sexual freedom but too timid to achieve it, fearing the wrong moral choice, longing for love.

At the heart of all of Ibsens works there is a war between the conflicting parts of his personality, almost transparently visible in the next of his plays that I directed: Little Eyolf. The play was written by a sixty-six-year-old man whose thirty-six-year-old marriage had been a source of quiet unhappiness to him and almost certainly more so to his partner. Hed returned from twenty-seven years in self-imposed exile in Italy and Germany to discover that he was revered at home. He began to audit his life in his plays: the conflict between love and work, between selflessness and selfishness, between comradeship and isolation, between the brightness of passion and the bleakness of unrealised emotions. In Little Eyolf he asks how can a marriage survive without sex, without mutual respect, without children.

To direct any play you have to try to understand the authors intentions. The best way of doing that is to write it yourself, but if somebody else has done the heavy lifting, then even copying out the text in longhand will help. If the play is written in another language you have, somehow, to climb inside it, to wear its skin: youre forced at every moment to ask what the author intended. I adapted the last three plays of Ibsen that I directed, working from literal versions with the original (Dano-Norwegian) texts by my side, always curious about the length and sound of the original lines even if their sense was only accessible with a dictionary. I tried to make the English of my adaptations live in a way that felt true to what I understood to be the authors intentions, but even literal translations make choices and the choices we make are made according to taste, to the times we live in and how we view the world.

All choices are choices of intention, and in order to get nearer to Ibsens intentions I rifled biographies and Google entries for any of his statements about any of his plays. This book, Ibsen on Theatre, not only does that work for you, it also contains material previously unavailable in English. For anyone interested in Ibsens playsactors, directors, students, audiencesits a marvellously accessible compendium of the thoughts of a man I now unhesitatingly describe as a very great playwright.

Richard Eyre

Acknowledgements

E diting any collection of Ibsens writings involves drawing on a wonderfully rich history of scholarship, but we are particularly indebted to the teams of scholars, editors, technical staff, and data-entry personnel behind the digital publication of Henrik Ibsens skrifter HIS (www.ibsen.uio.no) and IbsenStage (ibsenstage.hf.uio.no). These online resources have made it possible for us to collaborate while living in different cities and on different continents. Special thanks go to Narve Fulss, the HIS editor of Ibsens letters, and to Stle Dingstad and Jens-Morten Hanssen for their advice about our selection of Ibsens writings. We would also like to thank those people who have helped us with the fine tuning of this book: William Dunstone for his invaluable contribution in advising us on nineteenth-century English syntax; Michael Morley for translating the few letters written by Ibsen in German and French; and Torhild Aas for her excellent copy-editing skills. Finally, we would like to thank Nick Hern for inviting us to contribute to his