Dedicated to Carol and Will

I cant imagine life without them.

Contents

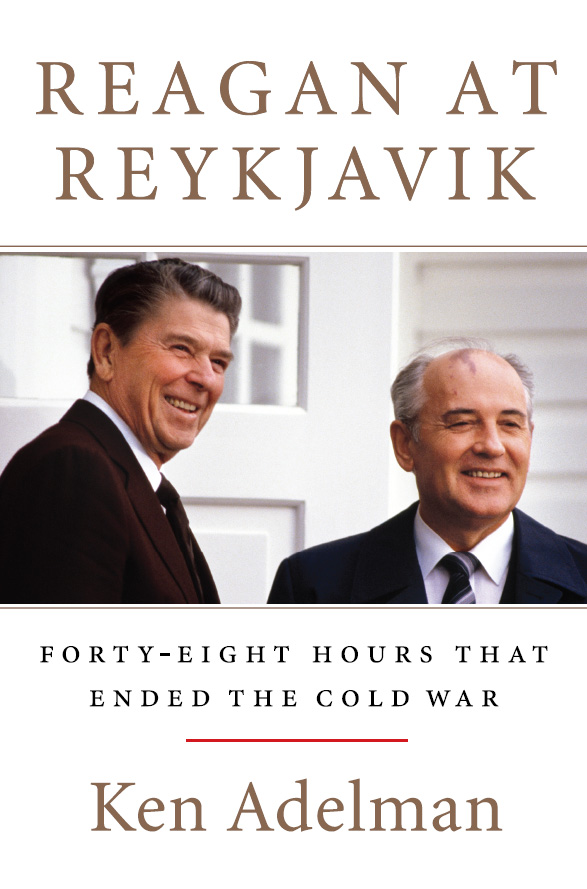

T he Reykjavik summit is something out of an Agatha Christie thriller. Two vivid characters meet over a weekend, on a desolate and windswept island, in a reputedly haunted house with rain lashing against its windowpanes, where they experience the most amazing things. The summit between Ronald Reagan and Mikhail Gorbachev on October 11 and 12, 1986, was like nothing before or afterwith its cliffhanging plot, powerful personalities, and competing interpretations over the past quarter century.

A decade later, Gorbachev felt the drama was something out of the Bard, William Shakespeare, rather than the Dame, Agatha Christie:

Truly Shakespearean passions ran under the thin veneer of polite and diplomatically restrained negotiations behind the windows of a cozy little house standing on the coast of a dark and somberly impetuous ocean. The accompaniment of grim nature is still lingering in my memory.

For those of us in the American delegation, Reykjavik was supposed to be an uneventful weekend, with the real action happening the following year at the real summit in Washington. Instead, in Iceland we rode an emotional roller coaster, full of twists and turns, ups and downs, all weekend long. NPRs Rod MacLeish deemed it among the most amazing events in diplomatic history, while the ace Washington Post diplomatic correspondent turned Cold War historian Don Oberdorfer called it one of the most controversialand most bizarrenegotiations by powerful heads of state in modern times. To Gorbachev, it was exhausting with its wearying and grueling arguments.

Unlike other summits and dramas, Reykjaviks plot unfolded off script. The session itself came as a surprise and ended up delivering surprise after surprise. We didnt know what to expect next or how it all would endnot just over that weekend, but over the months and years that followed.

Besides Reykjaviks gripping plot were its oversize personalities. Reagan and Gorbachev stand among the most intriguing and important characters of the twentieth century. For some ten and a half hours at Reykjavik, they dealt directly with one anothervoid of staff advice, detailed talking points, or guiding memosacting more like themselves than at any time in office.

Thanks to the now-declassified American and Soviet notes of their private discussions, we can peep through the keyhole of their small meeting room to see them, hear their back-and-forth repartee, and come to understand their core beliefs, patterns of thought, and fundamental characters in a way that history rarely offers.

Reykjavik changed each man, changed their relationship and thus that of the superpowers. The day after returning from Iceland, Gorbachev said on nationwide Soviet television that, after Reykjavik, no one can continue to act as he acted before. Neither man did, and neither country did.

Beside these two leading characters were two others in key supporting roles. Most constructive and then tragic was the chief of staff of the Soviet military, the five-starred Sergei Akhromeyev. Having been shrouded and operating behind the scenes for decades, he emerged at Reykjavik for a few shining hours to help change the course of history. He could never have imagined that his contribution would end up helping to destroy the country he loved and the life he led.

The other key character in this drama was Hofdi House, the cozy and stunning structure said to be haunted by a people inclined to believe such things. At the time of the summit, more than half of Icelanders believed in elves and leprechauns, including the countrys prime minister. Hofdi House provided a weird yet hospitable site for the worlds two most powerful men to meet.

As if its twisting plot, outsize characters, and unique setting werent enough, the Reykjavik summit has been hotly debated and differently interpreted over the years. Immediately afterward, it was universally deemed an abject failure since the two leaders left without a joint statement, clinking of champagne glasses, or promises of future meetings. They left each other glowering and, in Reagans case, steaming mad. The White House chief of staff, Donald Regan, asserted that the two would never meet again. The session was nearly universally condemned, even by those as astute in foreign policy as Richard Nixon, who declared, No summit since Yalta has threatened Western interests so much as the two days at Reykjavik.

The following year, 1987, Reykjavik received some acclaim when agreements reached over that weekend were signed in the White House as part of a sweeping arms control treaty.

Since thendespite the earth-shattering events of the fall of the Berlin Wall, the demise of Communism in Eastern Europe, the collapse of the Soviet Union, and end of the Cold WarReykjavik has mostly been relegated to a footnote in history, something akin to the Glassboro summit of 1967 between U.S. president Lyndon Johnson and Soviet premier Aleksey Kosygin. Specialists have debated the summits significance, particularly at four conferences held on its anniversaries, but their debates have largely remained thereamong specialists at conferences.

And most of those specialists believe that the momentous events of that era sprang from internal weaknesses in the Soviet economy rather than from any outside events, such as Reykjavik, or outside pressure, such as Reagans rhetoric or plans for strategic defense. Indeed, this view has become the conventional wisdom of how and why the Cold War ended.

With the gifts of historical perspective and declassified documentsboth of the Reykjavik discussions and of Soviet meetings, before and after the summita different interpretation has become possible, and possibly more accurate. I, for one, have come to believe that Reykjavik marked a historical turning point, by leading to:

1. a steady stream of unprecedented arms control agreements;

2. a remarkable decline in the number and danger of U.S./Soviet-Russian nuclear arsenals;

3. an unexpected flowering of the anti-nuclear movement worldwide;

4. and eventhe mother of all historical consequencesthe end of the Cold War itself.

The case for this interpretation will be laid out in the final chapter, bolstered by such standard methods of substantiation as expert witnesses, evidence, and logic.

One such witness, Mikhail Gorbachev, has been clear over the years. U.S. Secretary of State George Shultz, at Reagans side during Reykjavik, had a conversation with the last general secretary of the Soviet Communist Party some years after the summit, and described the scene:

We were sitting around with the interpreter, and I said, When you entered office and when I entered office, the Cold War was about as cold as it could get, and by the time we left it was all over. What do you think was the turning point?

He didnt hesitate a second. He said, Reykjavik.

And I said, Why?

Because, Gorbachev said, for the first time the two leaders talked directly, over an extended period in a real conversation, about key issues.

This is the story of what happened during that weekend, and what I believe to be its significancewhy it deserves to be called the forty-eight hours that ended the Cold War.

Thursday, October 9, 1986

Washington, DC

Ronald Reagan was beaming as he stood outside the White House on a beautiful Indian summer morning. He embraced his wife Nancy and then turned to acknowledge the greetings of the assorted members of Congress and his cabinet, who had come to wish him well and farewell. Attending a South Lawn departure ceremony was one of the perks of White House employment and the small crowd of staff, interns, supporters, and friends applauded enthusiastically.