Thank you for buying this ebook, published by Hachette Digital.

To receive special offers, bonus content, and news about our latest ebooks and apps, sign up for our newsletters.

Sign Up

Or visit us at hachettebookgroup.com/newsletters

For more about this book and author, visit Bookish.com.

Copyright 2006 by Tom Adelman

All rights reserved. In accordance with the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, the scanning, uploading, and electronic sharing of any part of this book without the permission of the publisher is unlawful piracy and theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), prior written permission must be obtained by contacting the publisher at permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

Little, Brown and Company

Hachette Book Group

237 Park Avenue New York, NY 10017

littlebrown.com

twitter.com/littlebrown

facebook.com/littlebrownandcompany

First ebook edition: May 2010

Little, Brown and Company is an imprint of Hachette Book Group, Inc. The Little, Brown name and logo are trademarks of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

ISBN 978-0-316-07543-5

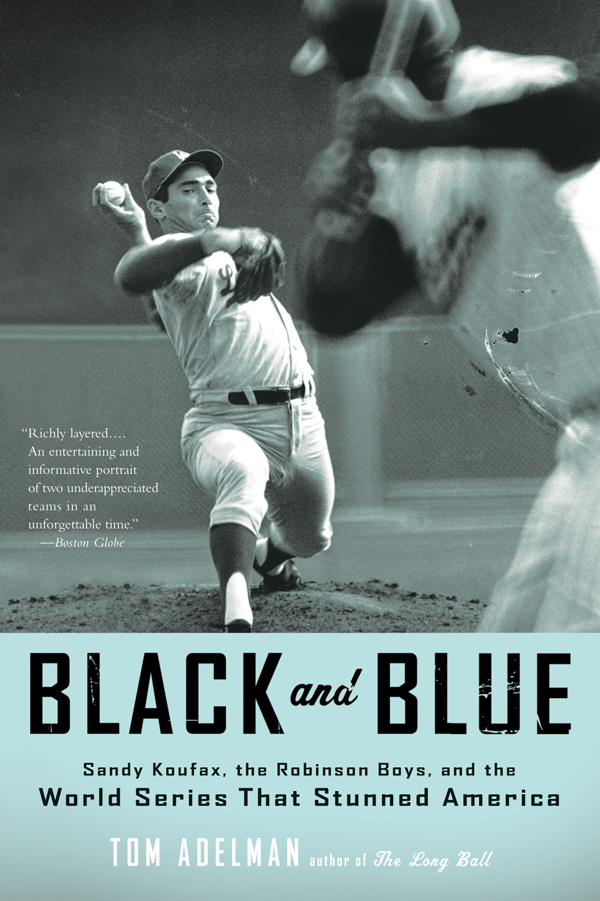

The Long Ball: The Summer of 75Spaceman,

Catfish,

Charlie Hustle, and

the Greatest World Series Ever Played

O ne cold afternoon in 1965, two weeks after Thanksgiving, the Cincinnati Reds telephoned Frank Robinson, their star outfielder,to inform him that hed just been traded. He was going south, they explained. To Baltimore.

Frank was stung. Naturally, there had been rumors; there always were. Hed heard that he would be sent to Houston; then it was supposed tobe Cleveland, and then New York. He hadnt really believed any of it, hadnt bothered paying much attention. Why trade him?For a decade, hed been Cincinnatis best player, regularly batting higher than .300, every season averaging more than thirtyhomers and one hundred runs batted in. In 1956 hed been a unanimous pick for Rookie of the Year, in 1961 the overwhelmingchoice for Most Valuable Player. He was the greatest run producer in the history of the Reds. The previous year, hed knockedin 113 runs, hit .296 with 33 home runs. Why deal your strongest hitter? It made no sense.

Well, asked Robby, whod you get for me?

Pappas, Jack Baldschun, and Dick Simpson.

Okay.

Theyd gotten three guys in exchange, not bad. Baldschun was a workhorse in the bull pen, Simpson a young, speedy outfieldersolid talents certainly, but essentially throw-ins, addenda. The main guy was Milt Pappas. He was a right-handerwith a swift fastball, a nasty slider, and, by late 1965, the best record of any starter in Oriole history. He was also nobodysfavorite, ostracized by his own teammates for behaving like a snot, viewed by the Baltimore organization as a hypochondriac,disdained by umpires and official scorers alike for his on-the-field tantrums.

Knowing little of this, Bill DeWitt, the owner of the Cincinnati ball club, welcomed the trade. His Reds, though powerful,were just shy of championship caliber. In 1965 theyd hit and fielded better than any other team in the league, remainingin contention until the seasons last week. DeWitts pitching staff, however, had given up too many walks and too many runs.Falling fast, Cincinnati had finished in fourth place. DeWitt was intent on fixing things, and his big idea was to unloadRobby before it was too late. He saw Frank as overvalued, a fading talent increasingly hobbled by leg injuries. When remindedthat the perennial all-star was only thirty years old, DeWitt shrugged. Thirty, he agreed, but an old thirty.

If there was one thing everyone in baseball knew about Frank Robinson, it was this: never make him mad. His temper focusedhis competitive spirit. Phillie manager Gene Mauch fined his pitchers if they brushed Frank back, and Dodger manager WalterAlston warned his staff against waking the beast, growing frustrated whenever his head-hunting hurler Don Drysdale workedRobby inside. Frank savored every challenge. He performed best when he had something to proveduring pennant drives, in televised matches,with a game on the line. Beanballs and boobirds only fueled Robbys concentration. Anger improved the quality of his play.And DeWitts comment infuriated him.

It was in this context that Frank Robinson, a muscular, ambitious African American every bit as seething and rancorous as the country itself, was dispatched down to Baltimore.

Had he hopped on a plane to fly there, Robinson would have soared above a nation on the brink of ignition. Crime and povertywere on the rise, along with claims of discrimination and police brutality. The civil rights movement had lost its patience.Peaceful sit-ins and freedom marches were giving way to increasingly militant demonstrations for racial equality. The SoutheastAsian conflict was shifting into the Vietnam War. Seventy-five million baby boomers were coming of age, many of whom werebeing randomly drafted to fight meaningless battles in a jungle half a world away.

The northern inner cities were growing progressively more restless, and the declining neighborhoods around Cincinnatis CrosleyField, Clevelands Municipal Stadium, Detroits Tiger Stadium, Chicagos Comiskey Park, Pittsburghs Forbes Field, and WashingtonsD.C. Stadium were particular flash points. Baseball season was being supplanted by riot season, the long, hot summers of themid-1960s less an invitation to ballpark repose than a call to urban warfare.

Raised mostly by his mother in a rough patch of West Oakland, Robby had grown up poor, across the Bay from San Francisco,the youngest of eleven children. His manner, from infancy, was swift and intense. He needed to be forceful just to survive,he later said, sharing a dinner table with that many siblings, with only their mom to keep the peace. So began a lifelong mission to prove his detractors wrong.

In high school, Robinson came under the tutelage of an exceptionally decent man named George Powles, a white coach who shapedmany impoverished black children into professional ballplayers. Powles expected his players to devote themselves fully tothe game. He taught Frank to think positively and play aggressively. Thanks to him, one week after graduating from McClymonds High School, at age seventeen, Robby signed a contract with theCincinnati Reds. His bonus was $3,500. The year was 1953.

He was in the minor leagues for two years, and it was there, out and about in America for the first time, that the talentedteenager suddenly encountered racism. Movie theaters and restaurants turned him away for being the wrong color. He accompanied his club through Utah and Idaho, around Oklahoma, from South Carolina into Georgia, unable to leave the backof the team bus to get food or even to use the bathroom. When at last theyd arrive at their destination, Robby would haveto stay somewhere else, across town in a room without air-conditioning, at a YMCA or in a private home. It was always crowded,and in the morning hed have to locate a Negro Cab to get to the ballpark. Once he took the field, the fans howled withindignant taunts and jeers. His every movement was mocked, his sexual preferences maligned, his familys name impugned. Whatcould possibly have prepared him for this? He had had an attentive and caring mother, loving siblings, enthusiastic encouragementfrom classmates and coaches of every color. Poor, yes, but a different America. Segregation floored him. You get angry,he acknowledged later, but one person isnt going to throw the thing down. His response, as always, was to turn their invectiveinto incentive, to drive himself all the harder in order to climb.

Next page